A grey afternoon in Paris unexpectedly turned into one of the most fascinating, educational perfume experiences I’ve had in a long, long time. It’s all thanks to Viktoria Minya. She gave me the chance to peek behind the curtain, and to glimpse a small portion of the life of a “nose.” We talked about everything from IFRA/EU restrictions on perfumes, how she studied to become a “nose,” some of the surprising things she deals with in perfume creation, and the very elementary basics of the raw materials that noses use to create fragrances. I hope you enjoy the glimpse behind the perfumed curtain.

Viktoria Minya. Source: Fragrantica.

Hedonist. Source: Parfums Viktoria Minya on Facebook.

Viktoria Minya is a perfume creator who founded Parfums Viktoria Minya, but also an actual, genuine, trained “nose.” Her debut perfume, Hedonist, is a gorgeous, luxurious, elegant, airy, honeyed-floral affair that I really loved. But I also enjoyed the little bit that I got to know of Ms. Minya herself in our email correspondence at the time. Then, a few weeks ago, close to the time of my departure to Paris, and by a complete fluke involving something else, we had a few email exchanges where I happened to mention that I would be in her city. Unfortunately, both our schedules seemed extremely complicated, and it seemed unlikely that we’d be able to meet.

Then, while roaming the streets of Paris one afternoon, and with some incredibly lucky timing that happened out of the blue, everything seemed to fall into place. I somehow found myself in her perfume studio, sitting across from an absolutely beautiful woman with the most unbelievably stunning eyes, and the warmest smile. (Not a single photo that I’ve seen of Ms. Minya actually does her — and her eyes — justice.) Ms. Minya had prepared a lovely selection of things for me to nibble on while we talked and before we went into her actual work area where she has her perfume “organ.” (See photo below.) As I ate some French cheese (yes, I said cheese! And she didn’t even know of my obsession with it!), I tried to focus on the conversation but those absolutely mesmerizing eyes made it a little hard at times. Plus, as usual for this entire trip, I was somewhat in a daze from sleep-deprivation.

As a result, I fear I don’t remember all the details of the technical stuff I learnt, but I thought I would share some aspects that I found really fascinating, from the issue of IFRA (the “International Fragrance Association”), to her studies as a nose, the black market for ingredients, and more. Then, later, I’ll share what it was like in her perfume studio with all the raw materials and the perfume oils. The photos I took suffered from the problem that I mentioned earlier in another post: my camera is dying, so some of the images are blurred and the writing on the bottles isn’t always completely clear. Hopefully, though, it will give you an idea of the sorts of things a “nose” may have in her arsenal, and the feel of that day.

Ms. Minya’s perfume “organ.” Photo: my own.

In terms of general discussion, one of the things that came up a few times was the impact of the IFRA and EU restrictions. You and I — consumers and buyers of perfume products — usually think about the impact in terms of its effect on us. We moan about chypres and oakmoss, we talk about reformulations, and we gripe about the sorts of perfumes available to us or the massive changes to perfumery in just the last five years alone. We almost never think of what it must be like for a “nose.” It’s not surprising, after all, because their world is so far away from ours. But it’s not for Ms. Minya.

As an actual, working nose, the IFRA/EU restrictions create a whole different set of problems for Ms. Minya than they do for us. For one thing, I get the impression that she finds that they stifle creativity. (She was too polite to say so, but that was my impression.) For another, the restrictions have an impact on a nose’s actual business dealings with clients. Ms. Minya may have her own brand and perfume line, but she also works as a nose for clients to create scents in accordance with their particular wishes. She gave me one example of a situation where a client requested that she make a perfume with certain ingredients at a certain level. Again and again, she had to say something to the effect of: “No, it’s not possible to that extent,” or “No, that is illegal in the EU.”

Chris Bartlett of Pell Wall Perfumes Blog is a perfumer and consultant who has an absolutely wonderful, useful, eye-opening and completely depressing listing of all the IFRA/EU ingredient limits for Category 4 (fine perfumes in an alcohol-based solution). Though his list is not yet updated to include all the changes from the 47th Amendment of June 2013 (yes, I realise how ludicrous and Kafkaesque that sounds), I still look at it from time to time, usually resulting in complete irritation and annoyance at the EU. I looked again at the listing upon my return from Paris and in light of my meeting with Viktoria Minya — and I saw it in a whole new light from the perspective of a “nose.”

Let me give you some examples from Mr. Bartlett’s list of IFRA’s standards and limitations as of June and before the 47th Amendment took place. Some of the terms may seem like gobbledygook to you, but just pay attention to the percentage numbers at the end of each line (or whether the ingredient is permitted at all in perfume creation), and things will eventually become clearer:

Cumin oil 0.4%

Eugenol* [clove oil] 0.5%

Farnesol* 1.2%

Fig leaf absolute Prohibited

Galbanum ketone (various trade names; 1-(5,5-Dimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)pent-4-en-1-one) 1.13%

Geraniol* 5.3% […]

Iso E Super 21.4% [ME: GOOD GOD!!!!!!!!!!!!!]

Jasmine Absolute 0.7%

Jasmine Sambac Absolute 4%

Lemon (expressed) 2%

Lime (expressed) 0.7%

Musk ambrette Prohibited

Oakmoss Absolute 0.1%

Opoponax 0.4%

Peru balsam (crude) Prohibited

Quinoline Prohibited

Rose Ketones 0.02%

Santolina oil Prohibited

Safranal (2,6,6-Trimethylcyclohexa-1,3-dienyl methanal) 0.005%

Safrole, Isosafrole, Dihydrosafrole~ Prohibited (EOs containing these permitted if total below 0.01%)

Savin oil from Juniperus sabina Prohibited

Styrax (from Liquidambar styraciflua macrophyla or Liquidambar orientalis only) 0.6%

Styrax (all other species) Prohibited

Ylang ylang extracts 0.8%

* – the main sources of these chemicals is in natural materials and you need to work out how much is in all the oils that contain them and keep the total in your product below the levels quoted here. These are some of the most complex standards to ensure compliance with.

NB- The limits for Oakmoss and Tree Moss are cumulative (so the combination of both must be below 0.1%)

I tried to include in that list a good number of things with which we common lay-people are familiar, but, also, a portion of the many things marked with a red “Prohibited” notice (even if I have no idea what some of them are). The fact that things like ylang-ylang is limited to 0.8%, lime to 0.7%, and oakmoss at 0.1%, while that bloody, godawful “ISO E Supercrappy” (™ Sultan Pasha) can be as high as 21.4% suddenly clarifies things a bit more to me. It’s not just that some perfumers love that ghastly, cheap, synthetic crap; it’s that they are running out of ingredients to use at any substantial, rich or useful levels! I mean, seriously, some poor flower is at less than 1%, while the laboratory-created, aromatic equivalent of a hospital morgue’s antiseptic is at 21.4%??! Plus, a portion of the ingredients on the list are completely illegal to use?! To me, and from my layman perspective, that doesn’t seem to leave perfume noses with a huge amount of original options or alternatives.

Source: CaFleureBon

Which brings us back to Viktoria Minya and her world. She went to school in Grasse, perhaps the heart and soul of the perfume creating world, and attended the Grasse Institute of Perfumery. I asked her about the program which is one-year long, and followed by internships within the perfume world. Within the program, the students take a variety of courses on such subjects as: natural and synthetic raw materials; fine fragrance formulation; legislation courses; evaluation courses; and even functional perfumery courses (how to create fragrances for soaps, shampoos, candles, shower gels, etc).

There was much more, too, but, again, the haze of a particularly grueling travelling schedule means I’ve forgotten some of the details. So, I did some research, and stumbled across a 2009 article called “Smelling like roses… or not” which actually quotes Ms. Minya as a student and which also talks about the way “noses” are trained:

In class, the students flared their nostrils against white tester strips dipped in scented, mostly clear liquid. The exercise tested their olfactory memories as they built on the more than 300 natural and synthetic odors they had memorized since the course began in late January. The task included identifying the scents’ compounds and family. […]

By the end of the yearlong course, which includes a mandatory internship at a fragrance company lasting several months, students will have acquired a lexicon of at least 500 raw materials; the rest of their creative arsenal, which eventually could include thousands of ingredients, will be developed in the field.

As for Viktoria, as that old article makes clear, lessons in building an olfactory memory bank sensitize the nose:

On a recent visit to a horse stable, Viktoria Minya had to hold her breath until she could step outside. And at home recently, the 27-year-old perfumery student has found she needs to take out the trash as often as three times per day. It’s a side effect of her developing olfactory organs: “I smell too much.”

The article also mentioned a few other interesting things:

“A perfume hides a story,” said Laurence Fauvel, a perfumer and one of the teachers at the school, which opened in February 2002. “To create something really new is very difficult.” […][¶]

An official at the school estimated that about [only] 20 star “noses” exist worldwide.

Mr. Fauvel’s comment reminds me of the common line in many writing classes about how every plot or novel has essentially been written before. It’s true, and I’m sure the same theme applies, broadly speaking, to perfumery as well. But, to bring things full circle to perfume notes, it certainly can’t help when IFRA and the bloody EU restrict your options even further in terms of quantity and type of ingredients. As Ms. Minya told me, there are no longer quite as many avenues for self-expression and artistic creativity.

Vincent Van Gogh, “Irises” (1889). Source: hdwallshub.com

She compared the situation to a painter being told that he cannot use certain paint colours on his canvas, while other colours are limited in amount. So, perhaps it’s more apt to talk about “vibrancy” instead of the broader terms of “originality” and “creativity.” If a painter is forbidden from using brown paint, if he can only use blue if it’s 0.7% of his overall creation, and if green is limited to no more than 0.1%, then how do you end up with Van Gogh’s Irises? You can’t. You get a watered down, diluted, much less vibrant composition that may be good — perhaps even very good, in some cases — but it won’t be the masterpiece that is the Irises.

Stephen Weller, IFRA photo, via The Scented Salamander.

In the faintest fig leaf to appearing fair, I suppose I should mention IFRA’s side of things. Stephen Weller, IFRA’s Director of Communication, has given a few interviews in France defending his organisation as the supposed savior of certain key ingredients. The blog, The Scented Salamander, states that Mr. Weller:

makes the particularly salient point in this exchange that without IFRA, a number of perfumery ingredients would have altogether disappeared from the palette of the perfumer as they have come under attack from the European Union and before that pressure groups voicing their concerns…

Weller explains in this new interview with Premium Beauty News how his organism permits a more nuanced approach to the dermatological and allergic risks presented by aromatic materials.

You can read more about his claims at the Scented Salamander, but they essentially include the argument that you should thank IFRA for saving oakmoss and other ingredients from complete eradication in perfumery. I can see his point in theory, but I have great difficulties with his attempts to portray IFRA as the purely protective, angelic and benevolent savior of perfumedom! And don’t get me started on the oakmoss. Yes, the EU is driving most of this, now, but, correct me if I’m wrong, I believe early IFRA regulations started all this.

More to the point, and to use a parallel, I don’t see manufacturing associations putting restrictions on factories who produce food items or on chefs in restaurants simply because there are some pressure groups who complain about nut allergies. Some of the EU proposals (like the ludicrous idea of possibly banning Chanel No. 5 that I’ve talked about in another IFRA/EU post) are akin to shutting down the Eiffel Tower simply because 1%-3% of the EU’s 503.5 million population may have vertigo. (It’s been estimated that “1 to 3 percent of the EU population… are allergic or potentially allergic to natural ingredients contained in fine perfumes, according to a report published in July by the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS), an advisory body for the European Commission.” [Emphasis added.])

And IFRA’s substantive actions don’t seem like true championship or defense of the perfume industry to me. For example, why aren’t warning labels enough? They put such warnings on cigarettes, and on pre-packaged food items that may have been prepared in a factory that had some nuts in it. Are perfumes actually more dangerous to people’s health than cigarettes??! Also, why are perfumes to be regulated with such ingredients as the amount of lavender or citrus oils, but massage oils are left alone? Presumably, that minuscule percentage of EU citizens who have allergic reactions — or just the mere potential thereof — might possibly decide to have a massage one day. Why are those oils fine, but the ones in perfumery — which allergic people can simply avoid using — subject to increasingly Orwellian, draconian measures?

I’m sorry, I got sidetracked and derailed in rather irrational rage, so let’s leave the issue of IFRA and get back to the realities of creating a perfume. There, even apart from ingredient limitations, there are other hurdles to originality, too. This time, however, they pertain more to the business tail-end of things for one who is a brand’s creator or founder. Take, for example, the simple, seemingly prosaic issue of a perfume’s name. Now, obviously, you don’t want to use another brand’s exact name for your new creation, but I wasn’t aware of just how tricky the issue might be for French perfumers. According to Ms. Minya, back in the 1980s, many French companies bought up the legal rights to a whole host of names — lots of them being common adjectives or phrases — for future use. Now, when you try to launch your new perfume, there is a good chance that they might sue you for using one of their vast stable of trademarked names.

Hedonist. Source: Parfums Viktoria Minya on Facebook.

I remember hearing this, blinking and having a light bulb moment when she explained that this old 1980s situation is the reason why so many French perfumes have some generic variation of “Rose de ___” or “Vanille de ____” as their name. To quote Ms. Minya: “This is why we have more and more names with numbers, botanical or common names of ingredients ( like “orange” ) and geographical names – because these cannot be trademarked by anybody.” I suspect this may be the reason why Neela Vermeire might have had to recently change the name of her upcoming Mohur “Esprit” to just plain “Mohur Extrait,” though I am just guessing. (I have not asked Ms. Vermeire, and I certainly don’t know for sure.)

While trademark concerns are hardly unique to France, the situation there seems a little more complicated for perfumers than for artisans or artists in other fields. Even if you can get the money to make a perfume, even if you survive the draconian IFRA/EU’s restrictions to make something good, even if you spend all the money for the further compliance minutiae, you still aren’t home scot-free. Now, you can’t even choose your perfume name without the risk of a lawsuit.

Yet, the real issue that I see is something much broader in reach: you need very big pockets to engage in the perfume game, and to survive. I’d like one day to explore the issue of perfume creation primarily from a perfume creator’s perspective, but it’s clear even now that the real bottom line is money and how hard it is for truly “niche” perfumers to flourish in light of so many minefields. Someone like Tom Ford — who is backed and owned by the Estée Lauder multi-national conglomerate — or Kilian Hennessey is obviously going to have a very different time of things than someone like Viktoria Minya, Andy Tauer, or Neela Vermeire.

To me, as a layman and outsider, each of the things discussed here seems to represent a noose tightening around the neck of a truly vibrant, creative, non-homogenous, flourishing perfume world where small voices have as much chance in the marketplace as the big behemoths. It’s a sad parallel to the overall conglomeratization of the world in general, from the media and entertainment industries to banking and the airlines. But the last time I checked, neither the banking nor airline worlds depended on creativity and the freedom of imagination, so it’s substantially worse when artistry is stifled in an industry like perfumery.

Size makes itself an issue for noses like Ms. Minya in some ways that surprised me. As promised, I’m going to spend a bit of time talking about the raw materials used in the perfume process. When I went into Ms. Minya’s actual perfume studio with its vast, impressive “organ,” I gasped. As far as the eye could see, there were bottles of ingredients. Everywhere! Not just the organ, but filling whole bookcases and even in a fridge. As I was exclaiming about the endless varieties of orange blossom, iris, or rose accords, Ms. Minya mentioned how obtaining some of the ingredients wasn’t easy. Apparently, some companies are extremely unwilling to sell in the sort of small order sizes appropriate to a small, individual perfumer or nose. I didn’t ask if the companies countered things by charging much more for orders that aren’t in bulk, because I never like to talk about money or intrude into someone’s financial matters, but I assume that it’s a frustrating hassle and obstacle at the very least.

So, let’s drop money, and move onto the actual ingredients in question. First, we should probably begin with the basic difference between a perfume oil and an essential oil. Now Smell This has an easy explanation that puts it much more succinctly than I could ever manage:

Essential oils are volatile, fragrant liquids extracted from plant leaves, bark, wood, stems, flowers, seeds, buds, roots, resins and petals, usually through steam distillation. In other words, they are raw materials that can be used to create perfumes. They are highly concentrated […].

Perfume oils are fragrance components, natural or synthetic, in an oily base rather than an alcohol base, and can be used directly on the skin.

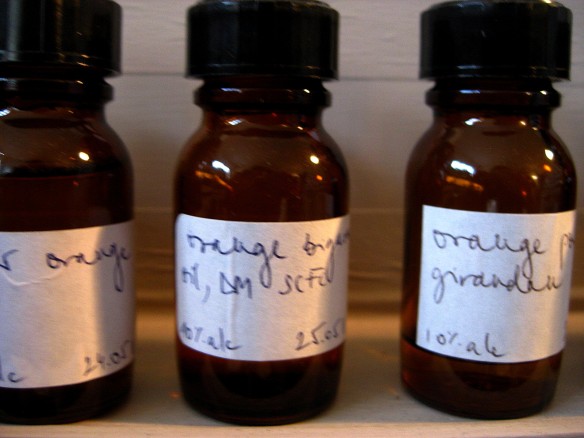

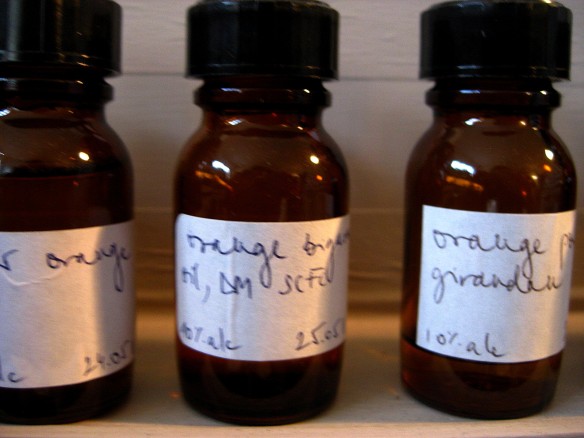

Now, here’s a glimpse of some of the things in Ms. Minya’s arsenal:

Perfume oils distilled in 10% alcohol. You can see various types of orange-related oils on the top shelf, rose on the middle, and things like vetiver on the bottom. Remember, this curves all the way around.

A fridge filled with fragile perfume oils, or oils of the weakest strength and diluted in 1% alcohol.

As you can see from these photos (which you can click to expand even more), there are two separate categories of ingredients. One are the oils on her curving, circular “organ” which are ingredients diluted in a 10% alcohol base. The other photo shows bottles in a fridge, and that’s where my memory failed me. All I could really remember is that the latter are very expensive and have a very fragile shelf-life, so they are usually kept in a fridge to ensure that they last longer. So I wrote to Ms. Minya to ask for help in clarifying the differences between the various bottles, and this was her response:

what perfumers are working with are what we call “raw materials”, some of them are liquid ( like most essential oils ), some are powders ( like vanillin – molecule present in vanilla, I am using the very expensive Natural version of it), some are resins ( like peru balsam or mimosa absolute). Every perfumer has their different habits, but I like to work with them in a 10% solution form, they are called 10% solution or 10% solution of … ( any given raw materials ). This helps me to directly smell the “end product” after formulation.

Oils like grapefruit and guaiac wood on the top row; magnolia and mandarin on the bottom.

Oils distilled in 10% alcohol. Here, orange bigarade and what Ms. Minya tells me is a “different origins orange oil.”

The raw materials in the fridge are simply weaker, more diluted solutions of some raw materials ( so like 1% or 0.1% solutions ) OR fragile raw materials, like rose oil, the citrus oils like bergamot, mandarine, orange, lemon and lime, or spices like nutmeg and safran, etc. [Emphasis added.]

More of the almost diluted 1% oils in the fridge such as Ylang-Ylang, Osmanthus and some sort of Sandalwood.

More of some of the delicate but weakest “finishing” ingredients. You can see Narcissus Absolute is one of the ones in the first row to the left.

[As a whole and generally,] the raw materials comes from the producers in “pure”. Then we dilute it with alcohol. 10% solution means 1 GR of rose oil -let’s say- and 9 GR of alcohol in a 10 ml bottle ( the ones you saw on my perfume organ ). 1% solution means 0,1GR of rose oil and 9,9GR of alcohol in a 10 ml bottle. The 1% solutions are for “fine-tuning”, sometimes it is to give a small aspect of a certain material, other times the given raw materials are very strong and we like to give just a tiny amount into the creation.

Just like the perfume you get from a boutique is a concentrate of pure mixture of raw materials which then is diluted with alcohol.

So, to simplify things if you’re a dodo like me, a 10% solution in Ms. Minya’s case has really just 1 gram of actual perfume oil, while a 1% solution has a mere 0.1 gram of the raw material.

Speaking of materials, Ms. Minya mentioned something just in passing that made me almost fall off my chair: there is apparently a whole, lurking black market for some ingredients! Guess in what context this issue arose? The thing about which I’m the greatest snob: sandalwood. It seems that my beloved Mysore sandalwood is so rare that some people — not all, but a tiny, unethical few, and primarily in the Far East or the Middle East — resort to the black market to obtain it. I imagine that this is an issue which applies more to some small-time or experimental perfumers who may not have the access to the very few places which still hoard have small quantities of Mysore sandalwood to sell at outrageous prices. It certainly seems related to the issue of how some companies selling raw ingredients are unwilling to fulfill small orders. Again, however, I do not like to discuss money, so I did not ask follow-up questions, but it is certainly something that gives one pause. A black market? Seriously? Who knew that perfumery could involve secret cloak-and-dagger skullduggery of the highest order?!

While I was absorbing this tidbit, Ms. Minya quietly assembled a little surprise for me: a blind testing of some of the concentrated perfume oils. She had actually just returned from Hungary where she’d given a lecture on the issue of perfumery, and had a lot of bottles previously prepared for a similar sort of demonstration. I can’t recall the precise percentage of what she made me sniff on strip after strip of the paper mouiellettes, but I believe it was the 10% stuff.

And it was quite an experience…. A number of notes that I’m very familiar with in actual perfume were wholly unrecognizable to me in essential form. Granted, I’ve never been particularly good at detecting the nuances of things from a mere paper strip and it’s a whole other matter on skin, but still! In a number of cases, I could detect the notes after the paper strips had time to breathe and develop, or, perhaps, to decrease from their concentrated opening moments. In other cases, however, the usually familiar notes smelled quite alien to my nose. Aldehydes? I wouldn’t or couldn’t have guessed correctly if you’d put a gun to my head. (In fact, I’m still finding it hard to believe that that odor was aldehydes!) Incense, one of my favorite notes? Forget it. I was absolutely convinced it was some type of wood, if my hazy memory serves me correctly. (Ms. Minya now tells me it was myrrh, but all it smelled like to me was dry wood.)

To my relief, and to avoid the complete destruction of my ego, some of my guesses at least hit upon the adjacent characteristics of a note. One of the first ingredients that Ms. Minya made me try smelled to me of smoke, amber, leather and wood. Well, all those things are either used with the ingredient, or are subset nuances of the note — which turned out to be….. patchouli. After she told me, it seemed somewhat obvious, but I have to emphasize the “somewhat” part of that statement. In reality, for me, the essence of one of my favorite ingredients really did NOT have the exact same smell as it did when mixed in with other stuff in an actual perfume. And this was the case quite often. (The one exception was the synthetic, Safranal, which smelled precisely as it did in some saffron-oud perfumes, was so strong that a mere drop on a mouiellette completely overwhelmed all the other paper strips, and thereby explained a whole host of overly intense, hotly buttered saffron perfumes that I’ve wondered about….)

On another test, Ms. Minya let me smell a concentrated perfume oil that I thought was a spicy geranium. It turned out a type of rose oil. Well, geranium in essential oil concentration has an odor that is rose-like, so… I was close?? Still, I can’t get over the aldehydes and incense myrrh being completely unrecognizable. (Have I mentioned that none of this was particularly great for the ego?!)

Joking aside, I truly loved every minute of it, and it was pretty hard to drag me away from the lure of those bottles. Each one seemed to contain a whole new world of smells that was different from what I had previously experienced. I’ve had a few cheap oils that I’ve used to add to scented heaters, candles and the like, but nothing quite like the hardcore oils I smelled in her studio! If I lived in Paris, I would definitely avail myself of the opportunity to take one of the classes or workshops that Ms. Minya offers.

Actually, at the time of my visit, I didn’t know that Ms. Minya actually teaches this stuff to dolts like myself! The other day, while doing my research preparation for this post, I noticed a section of the Parfums Minya website listing the services she offers as a nose. For example:

courses range from beginner level to levels tailored to the talents of more advanced candidates. The most popular themes are as follows:

• Main Olfactory Families

• Exclusive Natural Raw Materials

• Basic Formulation / Accords

• Perfume Creation

All course can be easily adapted according to clients’ specific needs. [¶] Price: Starting at 220 EUR ( five session course )

She also offers a cheaper workshop that let’s you create your own perfumed product, be it a fragrance, a candle, or a body product:

For those clients who would like to experience the joyful moment of perfume creation without going through the advanced studies of raw materials and ingredient classification, we propose a facilitated perfume creation workshop where clients will be manipulating fine essential oils and fragrance accords to go home with their own crafts.

The most popular themes are as follows:

• Perfume Creation Workshop

• Scented Candle Creation

• Scented Personal Care Creation (lotions, bath balls, etc. )

Price: 90 EUR for individuals. Starting price for groups: 50 EUR / person.

Hedonist in its handmade wooden box that is “fashioned to capture the sleek look and feel of snakeskin leather.”

Despite some of the issues mentioned up above, things are hardly doom and gloom for Ms. Minya. Her debut perfume creation, Hedonist, sold out in just a few months, and there is already a long list of pre-orders. Apparently, that does not happen very often, especially for one’s first fragrance. In the meantime, Ms. Minya is being kept busy as a nose for clients, but also in travelling to give lectures on perfumery-related issue.

The future looks bright too, with two new perfumes being slated for release in 2014. While they are works in progress and the details were kept secret, they are apparently going to be in the style as Hedonist with the same sort of philosophy of using “the most noble raw materials and giving them an indulging edge.” When pressed for a little hint or two, Ms. Minya merely smiled and said that the perfumes are centered around “the two most expensive flower essences existing in perfumery.” Aha! Iris! One of them has to be an iris scent!

Photo: my own. It does her beauty absolutely no justice at all!

I have to thank Ms. Minya for many things. One is for being a lovely hostess, but, more importantly for really taking the time to explain the technical and basic details of what is involved in perfume creation. More importantly, however, I want to thank her for pulling aside the curtain and giving us all a peek into a world that is often shrouded in some mystery. You and I, we buy perfumes; few of us know anything about the process of actually making them. Things like the building block steps, the basic procedural tasks of how to dilute the pure oils and in what amounts — those are a foreign world for the vast majority of us. Ms. Minya took the time to explain it to me not only in her studio where she welcomed me with warmth, but also in subsequent follow-up emails where she patiently answered my bewildered questions on what must be the equivalent of the “A, B, C” for her.

Just as importantly, she was open and candid throughout. As she wrote to me, “I think some brands are totally mystifying perfumers on purpose for the public. They say the magic goes away if people find out about the small details of our work, I disagree, I think the magic starts whenever they are let to have a look behind the curtains!!!”

I really hope you saw some magic today. I certainly did when I was in her studio. And, it turns out that the Wizard of Oz actually and truly is a bit of a magician. A very beautiful, incredibly sweet magician with gorgeous eyes and the warmest smile.

Note: Photos of Ms. Minya’s studio are all my own. Other photo credits or sources are as noted within the individual captions.

FURTHER DETAILS:

For additional information on Ms. Minya or Hedonist, you can check out her website, Parfums Viktoria Minya. If you’re curious about Hedonist and how it smells, you can read my extremely positive review here. Hedonist retails for $195 or €130 for 45 ml of eau de parfum. Hedonist can be pre-ordered directly from Viktoria Minya with shipment going out in November. (I assume that means that the new stock will arrive then, and so pre-orders will not be necessary for anyone who reads this post much later in time.) In the U.S., however, the perfume is currently stocked and available for purchase at Luckyscent. Samples are available from Luckyscent or from Surrender to Chance, which sells vials starting at $6.49 for a 1/2 ml vial. I think Ms. Minya has always offered a much better deal on samples, in terms of a cost per size basis: it’s €5 for what is almost 2 ml, if memory serves me correctly and I think there is free shipping.