Well, it’s slowly happening. The EU finally seems poised to act, according to a new report by Reuters. The article is entitled “EU Commission proposes tighter regulation of perfume ingredients” and was written by Astrid Wendlandt and Pascale Denis. To be clear, nothing in the article involves anything new. All that is happening now are the first, slow, official steps on events set into motion back in 2012.

In a nutshell, the situation is analogous to a Senate Sub-Committee advisory report going to the Senate who took their time to study it and, finally, after a while, decided it may be time to act on it with actual legislation. Those future legislative enactments have not been passed into law — yet — but things are much closer to that point than they were before. So many people blame IFRA, but the real source of perfume regulation is the EU. Yes, IFRA began all this years and years ago with minor restrictions, but none of them were actual law or quite as wide-sweeping in nature. It has taken the EU to act and make them legal mandates, binding on all who want to sell within their territory.

A few years ago, the EU asked its advisory, scientific body to look into things further. It commissioned the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) to come up with a report on allergens from perfumery, and that report was published in July 2012. You can read more about the group’s findings and recommendations in my post, 2013, the EU, Reformulations & Perfume Makers’ Secrets. As the new Reuters article summarizes, the SCCS advisory committee made several findings and suggested proposals:

The report called for drastically reducing the use of many natural ingredients found in perfumes, on the basis that 1 to 3 percent of the EU population may be allergic or may become allergic to them.

The recommendations of the report, if adopted by the Commission, threaten to seriously damage the fragrance industry.

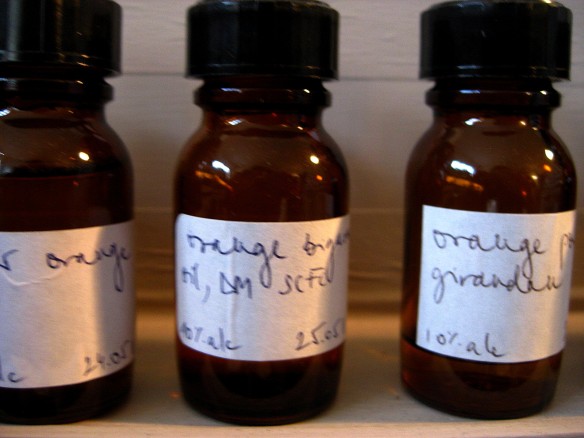

The report recommended restricting the concentration of 12 substances – including citral, found in lemon and tangerine oils; coumarin, found in tropical tonka beans; and eugenol, found in rose oil – to 0.01 percent of the finished product.

It also proposed an outright ban on tree moss and oak moss, which provides distinctive woody base notes in Chanel’s No.5 and Dior’s Miss Dior.

So, what is happening now? Well, the EU Commission is taking its first steps in acting on those suggestions. In essence, “the executive body” (as the Reuters article calls it) is giving its judicial response on the consultants’ 2012 findings. They are planning to follow the 2012 suggestions by proposing specific, upcoming action in a few areas:

- a ban of atranaol and chloroatranol, molecules found in oak moss and tree moss, two of the most commonly used raw materials because of their rich, earthy aroma and ability to ‘fix’ a perfume to make it last longer.

- ban HICC, a synthetic molecule which replicates the lily of the valley aroma and which has also been widely used by perfume makers.

- It is also proposing to significantly lengthen the list of molecules and ingredients perfume makers have to label on the packaging of their products to warn potentially sensitive users.

In short, the EU Commission appears to have flat-out accepted the proposed SCCS suggestion of banning oakmoss, but it is being more cautious with regard to its other suggestion of severely restricting 12 (or more) ingredients. What it is doing instead is what all legislative bodies do when confronted with more inclusive, drastic action: it is going to delay things further by asking for additional reports and investigation. The EU executive Commission has demanded

further research to determine what level of concentration should be used for those 12 ingredients and for another eight. These ingredients represent the spine of about 90 percent of fine fragrances, according to experts.

One reason for the hesitation to take immediate action is the wide-ranging impact that the SCCS’s recommendation would have. IFRA has stated that toying with those 12 ingredients would result in the formulas for over 9,000 perfumes being changed.

Speaking of IFRA, in the past, the organisation has pretended that it is the champion of perfumers, and it is only thanks to their actions that oakmoss has not been banned completely. In my piece on Viktoria Minya, the world of a “nose,” and what it’s like to be a perfumer in today’s current EU/IFRA regulated world, I discussed claims made by Stephen Weller, IFRA’s Director of Communications. According to the European blog, The Scented Salamander, Mr. Weller has given a few interviews in France defending his organisation as the supposed savior of certain key ingredients. The Scented Salamander states that Mr. Weller:

makes the particularly salient point in this exchange that without IFRA, a number of perfumery ingredients would have altogether disappeared from the palette of the perfumer as they have come under attack from the European Union and before that pressure groups voicing their concerns…

Weller explains in this new interview with Premium Beauty News how his organism permits a more nuanced approach to the dermatological and allergic risks presented by aromatic materials.

Mr. Weller would have you believe that IFRA is firmly on the perfumers’ side, acting as the sole barrier between the lobbyists who he argues are really at fault, and the total eradication of oakmoss in perfumery. I give my responses to that utterly ridiculous contention in the Viktoria Minya piece, but if anything should show IFRA’s true nature, it’s their reaction to these new 2014 EU developments.

In my favorite part of the recent Reuters article quoted up above, the writers give a very astute, subtle dig at IFRA by first providing their enthusiastic response to the EU executive body, and then, in the next paragraph, explaining who really backs IFRA. Take a look at their exact phrasing:

“We broadly welcome the proposed measures,” said Pierre Sivac, president if the International Fragrance Association, the perfume industry’s self-regulatory body.

Since its creation in 1973, IFRA, which is financed by scent makers such as Givaudan, New York-listed International Flavors & Fragrances and Germany’s Symrise, has restricted natural ingredients for a range of health reasons, from worries about allergies to cancer concerns. [Emphasis added by me.]

Yes, I’m quite sure that Givaudan would welcome the banning of certain natural ingredients and the severe restrictions of 12 others which form the body of 90% of perfumes. I’m quite sure they would….

[UPDATE 2/21/14 — I would like to draw your attention to something that is critical in all this, which is the scientific basis for the regulations in the first place. I’m wholly unable to speak to this with any clear knowledge, but Mark Behnke is most certainly qualified, thanks to an advanced degree in chemistry. He is the former Managing Editor of CaFleureBon who now has his own new site called Colognoisseur, which is where he recently posted an editorial on this issue. There, he writes:

The data used to determine the allergen potential of these molecules is scientifically and statistically unsound. […] The studies these bans and restrictions have been based on were performed one time at one concentration on 25 patients with no controls, positive or negative! This is what makes me shake my head as this is not good scientific practice and the conclusions made are very preliminary and possibly incorrect.

An even bigger flaw is the idea that it’s really only 23 molecules, so what? If these single molecules are restricted and banned it will have a ripple effect throughout many more raw materials. A natural oil is not a single molecule it is a combination of as many as hundreds of individual molecules. Any one of which could be identified as one of the “bad 23” which would then make that natural oil unusable as well. […]

I urge you to read his piece in full.

On the medical front, there is also the information provided in the comments from “Colin,” one of my readers who I believe is a doctor. He talks about the unsoundness of the conclusions in terms of actual medical impact of these allergens, writing

Most people who may be allergic to perfumes or specific scent chemicals have a skin reaction which is not dangerous or life-threatening in any way. A brief review of medical literature reveals only two, yes that is TWO, reported cases of anaphylaxis, which is the severe, life-threatening kind of allergic reaction. One occurred in a health care worker when a patient sprayed her directly in the face with 3 sprays of perfume (I’m completely serious, look it up–Lessenger JE. Occupational acute anaphylactic reaction to assault by perfume spray in the face. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:137-40). The other occurred when a mother sprayed her 2-month infant in the face with cologne. Neither of these would be considered by anyone to be a customary use of fragrance. Incidentally, in the case of the infant, the cologne contained menthol which was the ingredient the authors suspected to have been the main factor in triggering this response. Is menthol even on the list of ingredients of concern? Should any chemical be regulated if, in the recorded history of humanity, there have been but 2 cases recorded of any anaphylactic reaction and in both cases the perfume was being misused? 3 percent of a population is not a trivial number and would be potentially worthy of public health initiatives if that population were at risk. 2 cases out of the billions and billions of people in the world? Seriously? What a ridiculous waste of time and effort. This is why no reputable major health organizations are militating for any of these regulations. Banning a chemical because some people in the vicinity might get a migraine or the person applying it might get a rash makes little sense.

In short, on both the scientific and medical fronts, the empirical reasons for these regulations are faulty to begin with, never mind where the whole thing may go once the EU actually passes the complete 2014 laws.]

There is a charade playing out in all this, a charade in which we — perfume lovers — are the only losers. Only 1% to 3% of the entire EU suffers from perfume allergies, most of which are quite minor in nature. The European Commission claims that it truly cares about that tiny fraction of its citizenry, but it also firmly insists that it wants to avoid hurting the perfume industry.

“We have to find a way of ensuring security of consumers but also avoid causing damage to the industry,” said a spokesman for Neven Mimica, European Commissioner for Consumer Safety. [Emphasis added by me.]

Avoiding damage to the industry? Forgive me while I snort. In Grasse, the true home of perfumery with its vast fields of natural resources, the producers are so desperate over the SCCS proposal and the effect of any action by the EU that they turned for help to UNESCO. Yes, EU business concerns are turning to help to the bloody UN and to its UNESCO branch, a group better known for assisting Third World countries in dealing with poverty (!!!) or protecting historical treasures.

You think I’m joking, or that is hyperbole? Consider an article in Euronews from June 2013 discussing the panic amongst the producers of the natural ingredients of perfumery:

There are 2,500 lavender producers in France, covering 20,000 hectars. Grasse is considered by many to be the “capital of perfumes”. It is close to the lavender flower growing regions and home to Robertet, a world leader in natural fragrance production and perfume design. Their 22 branches worldwide turnover 400 million euros a year.

Robertet workers were shocked at the SCCS report with its long list of allergenic substances to declare, limit or ban. To adapt, the French perfume industry would need to pay up to 100 million euros, according to one of the directors. The cost to Robertet would be approximately five million euros.

Francis Thibaudeau, Deputy Manager Fragrance Division, Robertet told euronews: “Allergenic substances are part of perfume products. All the major perfumes would disappear if the SCCS proposals are implemented. Entire branches of perfume-making would be doomed. It would be the death of the industry… we could no longer use jasmine, ylang ylang sandalwood, or bergamotte. Those ingredients and essential natural products would no longer be used…” […][¶]

Meanwhile the tiny village of Montségur-sur-Lauzon is at the very heart of French lavender flower production. The summer air smells different. Fragrant. Here, Kriss, a young distillery manager, and a tractor driver nicknamed Mirabelle share the same fears: the thunderstorm forecast for later today, and the storm brewing over the European Commission’s apparent attempt to limit the use of coumarine, an allergenic substance naturally present in lavender flowers…

Kriss told euronews: “This European law on allergenic substances under discussion would be a catastrophe for all professions dealing with natural raw materials. Such a law would limit the use of those substances on a very low level. 90 percent of existing natural raw materials from plants could not be used any longer. The perfumers would have to change all their formulas…it would be like the debate to ban peanuts in Europe all over again. It’s just stupid.”

Meanwhile, the city of Grasse wants UNESCO to designate its local perfume tradition as World Heritage status. Lavender producers have the same idea: UNESCO should protect them against the ‘bad boys’ of Brussels. [Emphasis added by me.]

Yes, an entire city in the European Union is turning to a UN charitable organisation for help. I think that rather destroys the EU’s pretense of caring so much about the business industry.

That said, if there is a business that the EU wants to help, I’m not sure who it is. It’s too easy to claim that they are in the pocket of Big Business, but such conspiracy theories don’t hold up to a closer examination of the facts. LVMH is practically losing its mind over all this, and it’s certainly bigger, more powerful, and wealthier than either IFF or Symrise, two of the main manufacturers of aromachemicals and fragrance ingredients. The multi-billion dollar, privately owned Chanel corporation also has its panties in a twist, though as my earlier piece on the EU makes clear, L’Oreal (whose fragrances contain a lot of cheap crap) is quietly saying nothing. (No, L’Oreal, I will never, ever forgive you for what you’ve done to YSL fragrances.) Neither is Coty, apparently. (As a side note, IFRA President, Pierre Sivac, was formerly a powerful Coty executive. He also worked at Unilever, another big, beauty industry player that is not exactly known for its prestige fragrances.)

In my earlier piece on the EU, I quoted a discussion on the big split in the perfumery industry:

The proposals have also revealed schisms in the perfume industry – a lack of unity that makes it harder to lobby with one voice.

Brand owners such as Chanel and LVMH and scent-makers such as Coty, L’Oreal, Procter & Gamble, Givaudan and Symrise all have different goals.

LVMH, which owns Dior and Guerlain, and Chanel are lobbying Brussels to protect their perfumes, many of which were created decades ago.

“It is essential to preserve Europe’s olfactory cultural heritage,” LVMH told Reuters in an emailed statement.

So, again, if one has conspiracy theories about the EU being in the pocket of Big Business, then who is the business group who would actually be helped? Not the Europeans themselves, perhaps. In the opinion of one of the people quoted in the June 2013 Euronews article on Grasse, EU restrictions “would open up the doors of the European market for Indians and Chinese who would profit from European over-regulation and conquer our market shares…” I’m not quite sure how that would happen in Europe, given that anyone buying from the alleged Indian and Chinese profiteers would still have to abide by EU perfume laws, but it would certainly benefit producers and perfume manufacturers in the growing markets outside of Europe.

All these contradictions and competing interests really makes one wonder, yet again, why is all this happening? I honestly don’t know. To me, it simply isn’t logical. As I wrote in the Viktoria Minya piece, I don’t see the EU or manufacturing associations putting restrictions on factories who produce food items or on chefs in restaurants simply because there are some pressure groups who complain about nut allergies. Some of the early EU advisory suggestions (like the ludicrous idea of possibly banning Chanel No. 5 that I’ve talked about in another IFRA/EU post) are akin to shutting down the Eiffel Tower simply because 1%-3% of the EU’s 503.5 million population may have vertigo. (It’s been estimated that “1 to 3 percent of the EU population… are allergic or potentially allergic to natural ingredients contained in fine perfumes, according to a report published in July by the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS), an advisory body for the European Commission.” [Emphasis added.])

If the real concern is truly allergic reactions and not Big Business, then why aren’t warning labels enough? They put such warnings on cigarettes, and on pre-packaged food items that may have been prepared in a factory that had some nuts in it. Are perfumes actually more dangerous to people’s health than cigarettes??! Also, why are perfumes to be regulated with such ingredients as the amount of lavender or citrus oils, but massage oils are left alone? Presumably, that minuscule percentage of EU citizens who have allergic reactions — or just the mere potential thereof — might possibly decide to have a massage one day. Why are those oils fine, but the ones in perfumery — which allergic people can simply avoid using — subject to increasingly Orwellian, draconian measures?

Again, I have to emphasize that the new Reuters article is merely outlining the EU executive body’s first official, judicial response to earlier proposals. It is just like the Senate finally acting on a sub-committee advisory report from a few years before. With the exception of the Lily of the Valley proposal which I hadn’t heard of before or, more likely, had merely forgotten about, all of this has been on the table since 2012. However, now, the EU is finally taking the first slow steps to actually do something about it.

It is only a matter of time. Or perhaps it has already started. As the article notes, “industry sources say major perfume makers have already started modifying their formulas accordingly.”