Chilled iciness and warmth, silvered light and black darkness, thickness and airiness, herbal crispness with gourmand chewiness, all swirled together in one. That is Eau Noire, a surprisingly gourmand fragrance from Dior with almost a fractal juxtaposition of textures, notes, and sensations.

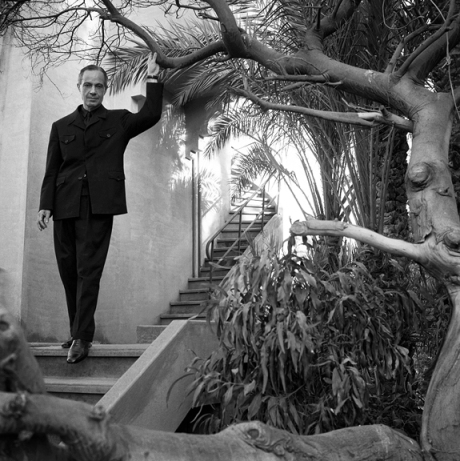

Eau Noir is part of Dior’s prestige line of fragrances called La Collection Privée. (The line is sometimes called La Collection Couturier on places like Fragrantica and Surrender to Chance, but I will go with the name used by Dior itself on its website.) The eau de parfum was one of the very first Dior Privée perfumes, and was released in 2004. Unlike most of its siblings, it was not the creation of François Demarchy, the artistic director and nose for Parfums Dior. Instead, it was created by the then-young perfume prodigy, Francis Kurkdjian, who went on to found his own perfume house, Maison Francis Kurkdjian, to great acclaim.

Dior categorizes Eau Noire as an “oriental aromatic,” and provides the following description:

An elegant gala spirit in an intense evening fragrance, swathed in mystery. This interpretation of Lavender in chiaroscuro reflects the atmosphere of the Château de la Colle Noire, an estate owned by the Designer, which is located in the Provence region.

Dior’s very limited — and I would argue, very incomplete — list of notes include:

White Thyme, Lavender, Liquorice, Vanilla Bourbon, and Virginia Cedar.

Fragrantica adds coffee, leather, spiced sage, and violets as well. And everyone includes immortelle, that tricky note that can smell of maple syrup, curry, and several other things as well. I definitely agree with a lot of those additions. So, in my opinion, the full note list looks more like this:

White Thyme, Lavender, Liquorice, Coffee, Immortelle, Vanilla Bourbon, Leather, and Virginia Cedar.

Eau Noire opens on my skin with the blackness of its name. It is a potent blast of licorice that is chewy and thick, almost resinously meaty in its depths, and, surprisingly, very chilled in feel. It’s followed by hints of thyme, coffee, vanilla, and a brief, transient pop of thick, yellow, spiced curry. It’s such an odd combination of iced, herbal, spiced and sweet notes that you have to blink. To be honest, the forcefulness of the licorice — so concentrated and thick that it feels like the distillation of every black anisic candy on the planet — is a bit alarming for someone like myself. Until just ten years ago, the mere smell of licorice would make my stomach heave and, though I now enjoy eating fennel/anise, I still won’t go near black licorice.

Nonethelesss, Eau Noire is oddly mesmerizing. I feel almost paralyzed and transfixed by the scent which becomes increasingly more nuanced and complicated. An unexpected floral note darts about, though it’s not immediately identifiable, at this point, as anything in specific. Then comes the immortelle, coffee, and caramel. The coffee is lovely, potent, and black, just like a freshly brewed cup combined with the scent of freshly ground expresso beans, and it works beautifully with the licorice.

The real key to Eau Noire, however, is the Immortelle (or Helichrysum) which must be in Eau Noire by the bucketfuls. Francis Kurkdjian has created a multi-faceted note, because the fragrance reflects almost all of immortelle’s various characteristics: dryly herbal floralacy; maple syrup; dry woodiness; and the curry that popped up that for a brief moment at the beginning. (No fenugreek, thank God.) I think that Eau Noire’s strong caramel note must stem from the combination of the immortelle’s maple syrup aspect with the Vanilla Bourbon. By the same token, if the coffee is not an actual, separate note, then I suppose it may be the result of the licorice mixed with the vanilla. Either way, Eau Noire is a fascinating blend of chewy, dense black licorice, sweet caramel, maple syrup, strong coffee, with flickers of herbs and a subtle undercurrent of rich vanilla.

Ten minutes in, Eau Noire feels warmer, sweeter, and more gourmand. The lavender keeps trying to brush his way onto the stage, only to get elbowed back to the sidelines by the other notes. Still, he tries valiantly, his little purple head darting up and down every five minutes above the big, blokey shapes of the licorice and maple syrup. The name “Eau Noire” feels almost misleading for a scent that is so much like a rich, unctuous, almost cloying dessert. It certainly wasn’t what I had expected.

By the end of the first hour, Eau Noire changes. The lavender is very prominent now, and there are hints of something woody in the base. The fragrance, as a whole, is a more modulated, balanced, and smoother blend that is equal parts licorice, coffee, and lavender. The dominant trio is trailed lightly by caramel, vanilla, occasional hints of maple syrup, and the lingering, muted traces of an intangible, abstract floral. The licorice fascinates me in its dense potency. Sometimes, it has a distinctly icy feel. At other times, there is a very subtle but unmistakable leatheriness to the note. At all times, however, it is chewy and almost resinous in feel, conjuring up images of something like a thick, black brownie, only made of pure licorice.

For the next few hours, Eau Noire remains largely unaltered in its core essence. The only differences are one of degree, not of kind, as there are subtle changes in the order, priority and strength of the various notes. The lavender waxes and wanes in strength, as does the power of the licorice, coffee, and caramel. Each one takes its turn leading the brigade, and sometimes, they all share equal time on stage in a well-blended swirl.

Dior’s description for the fragrance references the term “chiaroscuro,” an interplay of contrasts, and Francis Kurkdjian certainly succeeded here. For the first six hours, Eau Noire is a constant play on opposites: chilly iciness; silvery lightness; warm blackness; airiness and dense chewiness. The texture or depth of Eau Noire follows suit, because the visual feel of black, unctuous denseness is juxtaposed with the fragrance’s surprisingly airy weight. Don’t mistake me, Eau Noire is not weak in sillage — quite the opposite, actually — but the fragrance doesn’t feel opaque or heavy. Instead, it billows around you like a very forceful cloud with at least half a foot in projection from just 2 large smears. This is not a fragrance to overspray with reckless abandon if you work in a conservative office environment.

One thing I found interesting was how Eau Noire appeared from afar. Around the third hour, as the fragrance wafted all around me, I would catch little trails of it in the air. I’ll be honest, my mouth watered a little at the aroma, despite not generally being a fan of gourmand fragrances. There is something about Eau Noire that is utterly entrancing from a distance where it smells almost like a chocolate-coffee-caramel mix, and I found it much prettier than up close where you can separate out the notes into chewy, black licorice with lavender, coffee, and vanilla.

Another point is the impact of different temperatures on the scent. I tested Eau Noire this summer, and found it both cloyingly sweet and largely dominated from the start by the maple syrup aspect of immortelle. Though my tests always take place indoors under extremely cool air-conditioning, as well as outdoors, it was hot enough this summer that even short periods outside made Eau Noire’s sweetness really explode. I don’t generally believe in seasonality when it comes to wearing fragrances, but I think Eau Noire is much prettier in cooler conditions where its various accords blend in better harmony and it’s not quite so sweet.

Around the start of the fourth hour, Eau Noire starts to change again. At first, it’s merely a subtle difference in the base where flickers of a smoky woodiness start to stir, as the cedar attempts to make itself heard. More importantly, however, the immortelle reverts back to its maple syrup character instead of the primarily caramel facet it had shown up to now. It also starts to become increasingly more prominent in the fragrance’s composition. At the same time, the lavender starts to weaken, and the licorice loses some of its shape. The latter feels as though it has infused or melted into every other element in the fragrance. It also starts to feel extremely leathery in undertone, instead of just plain licorice.

Increasingly, Eau Noire becomes primarily an immortelle fragrance in nature. Maple syrup dominates, followed by leathery licorice. The lavender pops up and down like a Jack in the Box, but it’s no longer an equal partner with the other notes. The coffee has vanished, along with the vanilla bourbon. The cedar is barely noticeable, even in the background. At times, Eau Noire feels mostly like maple syrup with caramel, though it’s somewhat drier than those terms would suggest. Actually, I’m surprised that the fragrance has as much dryness as it does. On my skin, Eau Noire isn’t a fragrance that is oozing sugary syrup, though it is sweet. I suspect the cedar may be working indirectly from the base, along with the leathery undertones of the licorice, to keep some of the sweetness in check.

Eau Noire’s sillage also starts to change. At the start of the sixth hour, the fragrance loses some of its powerful projection, and hovers only an inch or two above the skin. It is still quite potent when smelled up close, but it no longer sends little trails out into the air around you. At the end of the eighth hour (!), Eau Noire finally becomes a skin scent, radiating primarily maple syrup with a faint hint of black licorice. In its final hours, the fragrance is merely a blur of sweetness. All in all, Eau Noire lasted an astounding 14.5 hours on my perfume consuming skin. Most of Dior’s Privée line has exceptional longevity, but Eau Noire exceeded all the ones that I’ve tried thus far.

I think Eau Noire is a very well-made, intriguing, and rather mesmerizing scent on some levels, but I have mixed feelings about it personally. As a whole, its dark sweetness was much more attractive than I had expected from its opening moments, especially once I got over the shock of that much licorice. Yet, despite how entrancing Eau Noire can smell from afar, I’m not hugely tempted to get a bottle. For one thing, I struggle with gourmands. In light of that fact, even if I had a bottle, I’m not sure how often I could wear such a fragrance. Eau Noire is lovely as a “once in a blue moon” sort of fragrance, but, with Dior’s increased prices and out-sized bottles, do I really want to spend $170 for the “small” 4.5 oz bottle just for occasional wear? For me, it doesn’t seem worth it, but I’m sure that a gourmand lover would find Eau Noire to be worth every penny.

Of course, that assumes that the notes wouldn’t go terribly south on your skin. Eau Noire doesn’t seem to be the easiest fragrance for some people, due to the immortelle. In fact, Fragrantica is littered with comments about some of Eau Noire’s odder manifestations: curried lavender; “curried creme brulée” mixed with cedar; “curry meets caramel;” a “sinister affair of spices and herbs… that reminds me of cough syrup;” and more. One woman thinks Eau Noire is best on a man, while a male commentator thinks it’s a woman’s fragrance.

On the other side are those who are ardent admirers. One commentator thinks it’s the most “sublime” lavender fragrance ever, with spices and a touch of leather, calling it a “real masterpiece of subtlety and spice.” A number of people had the same experience I did with the interplay of contrasting notes. To give you just one out of many similar accounts:

EN is an olfactory maze of ying-yang scents. It is warm and cold, sweet/spicy and woody/leathery, bright and obscure, simple and complex. Indeed, its name says it all: black water. You don’t know what you might get or what to make of it when you wade in it. The key here is to relax and take it in. Just breath in every punch that is thrown at you with your eyes closed and take in each aroma and you may start valuing the grand bal of scents that dance together here. It is a mary-go-round composition where each note underneath the core licorice and lavender combo decides to jump in randomly, show up for a moment, and then suddenly be replaced by another. You will not get bored with this polytonal composition.

Ultimately, I think that you will like Eau Noire only if you adore immortelle in all of its various characteristics (including the potential curry note), along with gourmand scents in general. If so, then Eau Noire will probably be true love for you. Take, for example, the Candy Perfume Boy, a blogger known for enjoying a number of gourmand perfumes, and who has said flat-out that, for him, Eau Noire is “a holy grail fragrance.” In his review, entitled “Eau My God!“, he writes, in part:

The first blast of Eau Noire is somewhat of a baptism of fire […] I find it to be a totally joyful experience, and unlike anything else that has come into contact with my nostrils.

Things fall into place pretty quickly and the top notes are very much about lavender and liquorice, two aromas that are very much intertwined. Each brings out the dark anisic, herbal, and sugary qualities of the other and the overall vibe is neither floral nor gourmand, it sits somewhere comfortably between.

Possibly the most striking aspect of Eau Noire is the HUGE amount of imortelle within the heart. […] Personally I love imortelle, it is perhaps one of the most complex and pleasing smells around, it smells like sweet maple syrup, burned sugar and curry. Much to my pleasure, Eau Noire seems to showcase each and every one of the imortelle flower’s wonderful facets in perfect proportion. […][¶]

I keep trying to think whether I have smelled a fragrance as damn good as this recently, and I really don’t think I have! Eau Noire is everything that a good fragrance should be; distinct, unusual, well proportioned and exceptionally blended, beautiful and of obscenely high quality. Bravo Dior!

It is the ultimate accolade from a man who knows (and loves) his gourmands. And he’s not alone in his passion for Eau Noire. A number of its fans talk about its beauty in this Basenotes thread discussing a possible Eau Noire clone, J’S Extè Man, from an Italian company. On the official Basenotes review post for Eau Noire, the fragrance has a total of Four Stars, with 67% of the 57 reviews giving it a full five stars and making such comments as: “Pure perfection. Completely flawless creation.”

On the other hand, 23% or 13 commentators give Eau Noire just one star, and the main reason almost each time can be summed up as “maple syrup and curry.” I cannot emphasize enough that you have to love immortelle in ALL its potential aspects to love Eau Noire. There may have been just a single, momentary pop of curry on me, but then, my skin has almost never brought out that side of immortelle. (Thank God!) Clearly, I’m one of the lucky ones, but you may not fare so well.

As a side note, a number of people have compared Eau Noire to Annick Goutal‘s Sables, perhaps the ultimate benchmark for immortelle fragrances. I haven’t tried it to know how it measures up, but one commentator in that Basenotes thread, “alfarom,” has a useful comparison. He states that Sables “pushes to the very limit the boldness of Helichrysum by introducing a massive dose of amber, [while] Eau Noir focuses on its gourmandic/syrupy aspect adding a liqorice effect and a strong vanilla base[.]”

As you can see, again and again, the issue comes back to immortelle and gourmands. If you share the gourmand sensibilities of The Candy Perfume Boy, and if you love both immortelle and licorice, then I strongly encourage you to give Eau Noire a sniff. If you love gourmands but immortelle doesn’t always work on your skin, then you should hesitate and perhaps consider a test. But if you loathe immortelle, licorice and/or gourmands, then run very, very far away. Eau Noire may make you utterly miserable.