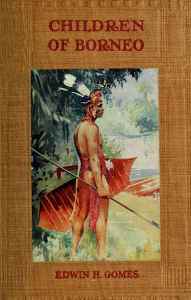

Serge Lutens wants to take you on journey to the heart of 19th century Borneo, an island on the equator, north of Java, and which now consists of Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. He wants to take you on the Dutch trading ships with their bales of raw silks and cocoa as they traversed the exotic seas on their way to the shops of Europe. And he does it via Borneo 1834, a perfume created with Lutens’ usual cohort in olfactory adventures, the famous nose Christopher Sheldrake. It was released in 2005 and, until 2010, was exclusive to Lutens’ Paris salon as part of the “non-export” line. At the moment, however, it is available worldwide via the Lutens website.

Fragrantica classifies Borneo 1834 as an “oriental woody” and lists its notes as:

patchouli, white flowers, cardamom, galbanum, french labdanum and cacao.

Bois de Jasmin, however, also adds in camphor and cannabis resin. The latter led me to some Google searches, with extremely amusing results, on what constitutes the exact smell of cannabis when in resin form. (My conclusion is that some people lead very… interesting… lives.)

On his website. Lutens explains his choice of name and the theory behind the scent:

Why did I pick 1834? That was the year Parisians discovered patchouli. In those days, it came wrapped in silk.

Imagine a woman of that time wearing a patchouli fragrance: she awaits her carriage, draped in her sable stole.

The famous perfume expert and critic, Luca Turin, provides even more explanation in his book, Perfumes: The A-Z Guide. In his four-star review of the fragrance, he says:

The famous perfume expert and critic, Luca Turin, provides even more explanation in his book, Perfumes: The A-Z Guide. In his four-star review of the fragrance, he says:

Apparently Lutens has determined that the first olfactory point of contact between Europe and the Far East took place there and then, in the form of the patchouli leaves used to wrap bales of silk. The patchouli was intended to keep moths away from the precious fabric (insects hate camphoraceous smells), but when the silk reached Western shores, elegant ladies wanted more of the smell. In other words, patchouli’s career in perfumery is a rise from bug repellent to luxury goods, a trajectory meteorically traced in the opposite direction by many contemporary fragrances. As often happens with Lutens-Sheldrake creations, the first sniff comes as a complete shock: the overwhelming impression is one of dark brown powder. Seconds later one realizes that this nameless dust is made of two components, patchouli and chocolate, skillfully juxtaposed (how?) so that neither the earthiness of patchouli nor the familiarity of chocolate prevails. Borneo 1834 is like Angel in reverse: instead of jumping out at you, it sucks you into its shadowy space. All the materials used are firmly rooted in the “orientalist” (aka hippie) style, yet the size, grace, and complexity of the overall structure make it the direct descendant of orientals proper like Emeraude and Shalimar. [Emphasis added for the names.]

The opening blast of Borneo 1834 on my skin is glorious. I absolutely love it. There is wonderfully resinous, boozy, sweet patchouli with bitter chocolate. The latter is more like the small, dark, cocoa nibs that you find in baking. There is a faint hint of camphor, but it’s light and plays off well with the smokiness of the patchouli and labdanum. It’s not the sort of smoke that you find in incense but, rather, a sweeter, much nuttier smoke accord. It makes me think of siam sesin, only amplified and combined with patchouli and cocoa. (You can read more about siam resin, along with labdanum, galbanum and some of the other notes in Borneo 1834 in my Glossary.) The patchouli has a great earthiness, almost like rich, black earth — moist, loamy and heavy. There is a faint hint of a musky, animalic note, too, almost like the sort of body funk that you would get from civet.

I don’t smell cardamom or the white flowers to any noteworthy extent. There is a floral note there, faintly peeking its head over the mighty patchouli, but I don’t think “white flowers” would really come to mind. If there is a floral note, I’d think of a pale rose more than white flowers, but it doesn’t really matter as the note is so faint as to be barely noticeable.

As for the notes given by Bois de Jasmin, I have never smelled a fresh, growing cannabis plant, let alone cannabis resin, so I set off to do some research. Google informs me that the former smells like slightly herbal, sweet, cut grass, while the latter can supposedly smell of anything from skunks to motor oil. I don’t smell fresh, sweet grass in Borneo 1834, and definitely nothing even remotely resembling skunks. I suppose one could say that there is a faint scent of car oil, but I think that the tarry, black note is more typical of a dirty, black patchouli or labdanum. Overall, the scent is dry in its sweetness, not cloying or synthetically sharp.

Thirty minutes in, the dark cocoa is on equal footing with the patchouli, and the light camphor note has vanished. There are times when the final result almost smells a bit like mocha coffee. It is too rich a smell to be considered “cozy,” especially as that is a word which I associate with softer scents that wrap themselves around you like cashmere or that make you want to snuggle under a blanket. Borneo 1834 is too dark for that. It is also too dry to be an edible gourmand scent, but it has some mystery and layers, especially in its opening. I truly adore those opening notes of patchouli which make me think, “this is what patchouli should smell like more often!”

I’m much less thrilled with the middle stages and the dry-down. Two hours in, the musk and animalic notes start to become much more pronounced. It is at this stage that the sillage lessens a little, though it is still somewhat noticeable. (Three hours in, the perfume becomes close to the skin, though there is still great longevity.) The animalic notes become more and more prominent with every hour, and the final dry-down stage is almost entirely earthy, slightly intimate body funk.

It’s hard to explain the scent here. It’s not intimate like someone’s private parts, it’s also not exactly musky, and it’s most definitely not like ripe, extreme, unwashed body odor. It’s sort of a mild variation of the two, a “skank” note like that from a very warm, faintly sweaty, slightly sweet, almost musky body after a long session at the gym. Perhaps, musk and sweet “dried sweat” may encapsulate some of it, but only a portion of it. Either way, there is a linearity and earthy singularity in the middle and final stages which is fine, if you like animalic notes. I don’t. Which is why I much preferred that absolutely lovely opening with its boozy notes evocative of siam resin, its luscious patchouli and its dry cocoa.

That dark, black, and faintly bitter, cocoa accord is just one of the things that separates Borneo 1834 from Christopher Sheldrake’s other patchouli creation: Coromandel (for Chanel‘s Les Exclusif line). Created with Jacques Polge, both perfumes share chocolate and patchouli notes, which is probably why they are so frequently discussed in the same breath. To me, however, Coromandel is an extremely different scent. In fact, I’d consider them to be like night and day. I found Coromandel to be all burning smoke, white cocoa and powdery vanilla, resembling a chai latte at times. The strong incense and frankincense notes dominated the sweet patchouli; it was a frankincense and incense perfume first and foremost. At its heart though, Coromandel is a cozy scent with powdered vanilla and tonka; it is light and somewhat multi-faceted. Borneo 1834, in contrast, is a dark powerhouse of patchouli, bitter cocoa dust and earthiness, and it’s not extremely complex. In fact, I’d say that it only has two stages, each of which is quite direct: patchouli chocolate with some camphor, resin and smoke; and earthy, animalic notes.

Freddie from Smelly Thoughts, a great perfume blog, loved the perfume throughout all its stages and didn’t seem to note any animalic body funk. His review is useful, especially as it compares Borneo 1834 to Thierry Mugler‘s infamous Angel:

So patchouli + chocolate = Angel? Not quite. The patchouli here is lavishly sleek, whilst being familiar in its dank, deep scent – it remains tame and completely in control. The sweetness in Borneo, unlike the Mugler, is also in complete control, richer – more exotic, with a delicate camphor laying over the top – adding an almost medicinal astringency to the patchouli and cocoa. The camphor is far from the intensity of Tuberuese Criminelle (for example), and instead has the sheer, sharp aspect that some great ouds have. It adds an age and a chilling subtlety to the foggy atmosphere.

I get a very subtle tobacco, as well as a liquorice note – in the same, but more toned down, style of Parfumerie Generale’s Aomassai. All intermingled with the cocoa and bitter patchouli, Borneo 1834 is dark and perplexing whilst being light and delicate on the skin.

The fragrance remains relatively linear, with a wonderful resinous base acting like a dark, sticky veil. The resins give off that breathy/slightly sweaty feel that they sometimes do (I normally get this with myrrh), I’d almost have thought there was the tiniest bit of cumin in here, but the fragrance isn’t spicy at all.

I think Freddie’s reference to cumin indicates that he may have smelled some animalic funk too, but obviously, it was in no way as extreme on him as it was on me during those final hours. All in all, Borneo 1834 lasted about 9 hours on me, with the animalic funk being a large part of the last (low sillage) 6.5 hours (and all of the final 3 hours). It is the main reason why I didn’t love the fragrance, though it’s an absolutely gorgeous scent in its opening notes.

Borneo 1934 is a scent that is definitely well-suited to winter and, if you love patchouli, well worth a sample sniff. If you try it, let me know what you think. I’m particularly curious to know if you have a similar experience as I did during the final hours.