I was recently granted the enormous honour and privilege of interviewing Serge Lutens. He was not in Paris during what had originally been intended to be a short stay on my part, so he kindly offered me a written interview. I cannot express my gratitude enough; even for someone as verbose as myself, there are truly no words to adequately express my appreciation, and how excited I was to receive the news.

Tag Archives: Serge Lutens

Serge Lutens Santal de Mysore

A taste of India. It’s hard not to talk about food when discussing Santal de Mysore, Serge Lutens‘ dark, gourmand tribute to that rare, precious Indian wood. Once abundant, Mysore sandalwood is so depleted and protected that it might as well be extinct for everyone but perfumers with the deepest pockets. In the case of Santal de Mysore, I think some clever olfactory alternatives have been used to recreate the dark, deep, spicy, smoky smell of Mysore sandalwood in a fragrance that is as much about food as it is about the precious wood.

Santal de Mysore is an eau de parfum that was created with Lutens’ favorite perfumer, Christopher Sheldrake. It was released either in 1991 or 1997, depending on what you read, and the only reason that is significant is because a special anniversary 50 ml bottle seems to have been issued at some point in time. The bottle is significantly cheaper than Santal de Mysore’s usual bell jar form, and is even discounted further on a few online retail sites. Normally, however, Santal de Mysore is considered one of Serge Lutens’ non-export Paris Exclusives that is only available at his Paris headquarters or at Barney’s in New York.

On his website, Lutens gives a brief description of the fragrance that hints at its notes and makes explicit its extremely spiced nature:

What incredible sandalwood!

This scent takes spices to the limit – they nearly cry out against the sandalwood base. One perceives saffron and, strangely enough, wild carrot.

Sweetness paves the way for a blast of heat!

The perfume notes are, as always, kept secret but the list — as compiled from Luckyscent, Fragrantica, Barney’s, and the Lutens statement — seem to include:

Mysore sandalwood, cumin, spices, styrax balsam, caramelized Siamese benzoin, saffron, cinnamon, rosewood, and wild carrot.

Santal de Mysore opens on my skin with a burst of spices. There is light curry, followed by leathery burnt styrax resin with a charred caramel aroma, saffron, a slightly herbal note that smells exactly like buttered dill, and a touch of sweetened carrots. I’m actually a little surprised by how the much-maligned curry note, noticeable as it is, feels so light. Perhaps a better description is to say that it doesn’t smell of the stale, cumin, body odor that I had so feared, or of really potent, yellow curry. Instead, for me, the strongest aroma is actually hot buttered dill and, specifically, a dill pilau or rice dish in Persian cuisine called Baghali Polo (or sometimes, Sabzi Polo). (There is a recipe for Baghali Polo with lovely photos at Cooking Minette.) Santal de Mysore is more than 75% Baghali Polo on my skin, right down to the little blob of melted saffron butter that some chefs put on top of mound. I really couldn’t believe it, but there is absolutely no doubt at all in my mind of the similarities.

There is a spicy wood note underlying it all, but it doesn’t smell like Mysore sandalwood to me. I’ve stopped hiding the fact that I’m a complete sandalwood snob, but that has nothing to do with it in this case. Santal de Mysore doesn’t smell of sandalwood in its opening minutes primarily because the curry, herbal, spiced accords overwhelm everything else in their path. This is a primarily a food fragrance on my skin, not a woody one.

Five minutes in, the styrax’s burnt, blackened aroma becomes less harsh, and the resin takes on a slightly tamer aspect. Now, it merely smells very dark, chewy, and balsamic, with sweetened leather, caramel and smoke swirled in. Flickers of cinnamon and saffron dance quietly at the edges, adding a spicy richness to the woody foundation, but I still think that this is “Mysore sandalwood” only by virtue of being built up by additives, instead of the real thing. My belief is underscored by a very definite whiff of something synthetic in the base which gives me a tell-tale pain behind my eye each and every time I take a very deep sniff up close.

So, I looked up sandalwood aroma-chemicals, and I would bet that Santal de Mysore uses Ebanol. Givaudan describes it as follows:

Olfactive note:

Sandalwood, Musk aspect, Powerful

Description:

Ebanol has a very rich, natural sandalwood odour. It is powerful and intense, bringing volume and elegance to woody accords and a diffusive sandalwood effect to compositions. Ebanol is highly substantive on all supports.

Givaudan also sells something called Javanol, and there are elements of something similar to its description which pop up at the final stages of Santal de Mysore. Javanol‘s description reads:

Olfactive note:

Sandalwood, Creamy, Rosy, Powerful

Description:

Javanol is a new-generation sandalwood molecule with unprecedented power and substantivity. It has a rich, natural, creamy sandalwood note like beta santanol.

I don’t know about Javanol due to the “rosy” description given above, but I wouldn’t be surprised if Santal de Mysore contained Ebanol. For one thing, the woody note in the fragrance smells extremely synthetic, but also dark and powerful. For another, have I mentioned just how rare it is for a fragrance to have true Mysore sandalwood these days? Finally, there is a support from another skeptic, Tania Sanchez. In her book with Luca Turin, Perfumes: The A-Z Guide, she diplomatically and tactfully writes:

Sandalwood oil from Mysore, India, was for a long time both fairly cheap and gorgeous — which is probably why it was overharvested to the point of needing government protection. I have a small reference sample of the real thing, with its inimitably creamy, tangy smell of buttermilk. I have no idea if Santal de Mysore manages to use any of it or if it depends on the Australian sandalwood (totally different plant and material) or synthetics, because it aims to cover any gaps with an overpowering coconut-and-caramel accord reminiscent of Samsara, a tropical fantasy of rum in oak barrels for armchair pirates.

I don’t smell coconut and I personally don’t see the similarities to Guerlain‘s Samsara, but I fully agree that Christopher Sheldrake must have sought to cover the gaps created by the use of synthetics in Santal de Mysore’s base by adding an overpoweringly strong spice and food element as a supplement. I may be a sandalwood snob, but that doesn’t change my impression that the “Mysore sandalwood” aroma is an artificially created construct, and it smells like it.

It takes less than 20 minutes for Santal de Mysore to start to shift. The fragrance softens, and drops in projection surprisingly quickly on my skin. Yet, it’s still very potent — even a little sharp — when smelled up close. It’s an intense bouquet of dill, buttered rice and light herbal, cumin curry, followed by saffron, sweet carrots, and chewy, gooey, thickly resinous black sweetness atop a base of spiced, synthetic woods. It’s odd, unusual, very foodie, interesting, somewhat appealing, and somewhat off-putting — all at once. By the 90-minute mark, the green, herbal spiced elements feel even stronger as the styrax’s slightly leathery, burnt caramel aroma continues to soften.

I have to wonder if there is fenugreek in Santal de Mysore, along with something like dried leeks. There are whiffs of something in the fragrance that very much resemble bottles I have of both herbs in my kitchen. Whatever the specifics, the “curry” in Santal de Mysore smells to me like something green in nature, more than spicy red or yellow. To be specific, it’s more along the lines of a Saag than a Korma or Rogan Josh curry made with a possible Garam Masala base. The cumin is there, lurking below, but I truly don’t think it’s as predominant as the more herbal, green curry elements. Even stronger is the burnt caramel aroma that is perhaps the first real thing you smell from a distance.

By the end of the second hour, Santal de Mysore turns creamy, smooth, and much better balanced in terms of its spices. There is almost a floral nuance to the deep woods, but the synthetic element remains as well. On some spots on my arm, it’s even a little sharp. Around the 3.5 hour mark, the herbal notes feel almost solely like fenugreek and dried leeks, rather than the earlier buttered dill rice. The dominant bouquet, however, is of cinnamon mixed with burnt caramel. Santal de Mysore’s sillage drops even further, and the fragrance now floats a mere inch above the skin.

The perfume’s final dry down begins near the middle of the sixth hour. Santal de Mysore finally — finally — smells primarily of the eponymous woods in its title. It’s rich, deep, smoky, sweet, dark, and beautifully creamy. The woods are now the sole star of the show, though they coat the skin like a veil. The sandalwood probably isn’t real, given the way the woods smelled so synthetic earlier on, but the overall effect is definitely that of Mysore woods. I feel like singing Etta James’ famous song, “At Last.” The lovely drydown continues for another three hours or so, until the fragrance finally fades away as sweetened woods. All in all, Santal de Mysore lasted just shy of 10.25 hours on my skin, with moderate sillage that turned quite soft after a few hours.

How you feel about Santal de Mysore will depend on a few things: your thoughts on curry and cumin, and your patience. Whether your read the comments on Fragrantica or that of samplers/buyers on Luckyscent, it’s always the same issue. For many people, the fragrance is simply too foodie, with curry being the main problem. For a few, it’s the burnt caramel that is the issue. For others, however, the fragrance’s final drydown is worth it, and they urge patience with the early notes, arguing that they are short in duration and quickly mellow into beautiful sandalwood. To give one example, a Luckyscent commentator wrote:

i wish i could afford jugs of this stuff. it is a tricky one, though! at first, it smells gourmande — curry, black pepper, and butter. delicious to eat, but not so great to smell liek a kitchen. oooh, but wait for it… if you are a sandalwood lover, it is worth the wait. and you don’t have to wait long! on the skin, it mellows out (and warms up!) really quickly. the harsh foodie smells dissipate in maybe 5 minutes, and then the silky road down sandalwood lane begins. this sandalwood is deep, warm, rich, and buttery. it is maybe 2:1 sweet:spicy as sandalwood goes. but you know how some sandalwoods are lovely, but kind of mixed up with vanilla or amber scents? this one is subtly more smokey, spicy, and just enough of a sour or a bitter touch to balance out the sweet buttery parts so that they are not overwhelming. this is a rich, deep sandalwood, as long as you are not turned off by the weirdness of its first few minutes.

There are numerous opinions on the other end of the spectrum, however, and they are probably best represented by this Fragrantica review:

Great scent if you’re… an Indian chef ;), as it smells exactly the same as curry. Disturbing cloud of heavy cumin and nose-drilling curcuma. No trace of sandalwood or benzoin whatsoever. Literally spicy scent that is harsh and nauseating at the same time. A big no-no..

I’m afraid that Santal de Mysore isn’t for me. I simply don’t like foodie scents in general, and I would have great difficulty walking out of the house smelling of either Persian Baghali Polo or Indian Saag. If it were merely a matter of minutes, I could deal with it, but it was hours and hours on my skin. You may have substantially better luck, but, in all cases, you have to be able to withstand the curry aspects of the opening stage. If you’re one of those people who is utterly phobic about cumin in all its possible manifestations, then I would advise staying away from Santal de Mysore. If you love sandalwood above all else, and enjoy gourmand scents, then you may want to exercise some patience and see how things develop on you. One thing is for certain, Serge Lutens and Christopher Sheldrake truly give you an olfactory carpet ride to India.

DETAILS:

General Cost & Discounted Sales Prices: Santal de Mysore is an eau de parfum that comes in a discontinued 1.7 oz/50 ml size and in a 75 ml bell jar size. The retail price of the small 50 ml bottle is $200, while the bell jar costs $300 or €135. However, Santal de Mysore is currently discounted at FragranceX which sells Santal de Mysore for $164.50, and Bonanza which sells it for $167.57. Parfums1 sells Santal de Mysore for $180, with free U.S. shipping and no tax.

Serge Lutens: Santal de Mysore is offered only in the bell jar version on the U.S. and International Lutens website (with other language options also available), and costs $300 or €135.

U.S. sellers: Santal de Mysore is available in the 1.7 oz/50 size for $200 at Luckyscent and Beautyhabit. It is available in the $300 bell jar version from Barney’s with the following notice: “This product is only available for purchase at the Madison Avenue Store located at 660 Madison Avenue. The phone number for the Serge Lutens Boutique is (212) 833-2425.”

Outside the U.S.: In Canada, you can find Santal de Mysore at The Perfume Shoppe for what may be US$200, but I’m never sure about their currency since it is primarily an American business with a Vancouver store. They also offer some interesting sample or travel options for Lutens perfumes. Elsewhere in Europe, it’s extremely hard to find the old 50 ml bottle, leaving your only real option to trek to Paris to get the bell jar. I couldn’t find any UK retailers. However, France’s Premiere Avenue has the 50 ml bottle and sells it for €106. I believe they ship world-wide, or at least through the Euro zone. In Australia, the 50 ml bottle of Santal de Mysore is sold on BrandShopping for AUD$160.95 and on HotCosmetics for AUD$217. In Russia, I found what appears to be SergeLutens.Ru which sells Santal de Mysore in the 50 ml bottle, but I don’t think Serge Lutens has a Russian website. It’s clearly a vendor of some kind, though.

Samples: You can test out Santal de Mysore by ordering a sample from Surrender to Chance where prices start at $3.99 for a 1/2 ml vial. There is also a Five Lutens Bell Jar Sample Set starting at $18.99 where you get your choice of 5 non-export Paris Exclusives with each vial being a 1/2 ml.

Serge Lutens Profile – Part II: Perfumes, His Inspiration & The Search for Identity

In Part I of this two-part series, we looked at the life of the visionary who is Serge Lutens, a lonely man, born in war, unwanted by many in his family from the time of his birth, whose very existence was considered to be “a problem,” but who went on to revolutionize the worlds of fashion, beauty, photography, and perfumery. Now, in Part II, we’ll talk about his philosophy and approach to perfumery, as well as the sources of his inspiration. We’ll address the issue of inaccessibility and exclusivity, and his views on such issues as whether perfumes are aphrodisiacs, what he thinks about fragrances being unisex, and how his creations are ultimately about the search for identity. (You can also turn to my exclusive interview with Serge Lutens himself if you are interested in learning more about the man.)

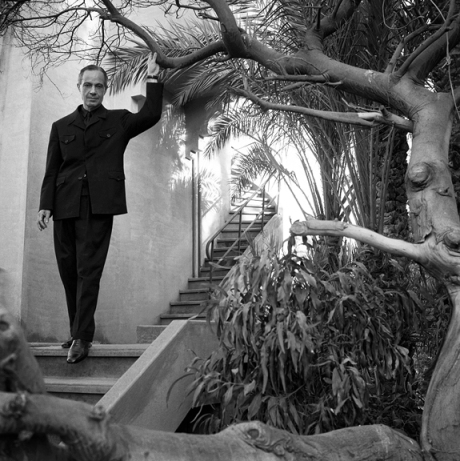

Photo: Marco Guerra, taken at Serge Lutens’ Marrakesh villa. http://marcoguerrastudio.com/?projects=portraits

SERGE LUTENS & PERFUMERY:

Like every artist, Serge Lutens reveals a little about himself in each of his creations. For example, Tubereuse Criminelle shows his love for Baudelaire (who is my favorite poet as well), while De Profundis reveals, depending on your interpretation, either a spiritual appreciation for the Psalms or his enjoyment of Oscar Wilde. Yet, Serge Lutens’ intellectualism is clearly drawn to the darker things in life. Baudelaire, after all, is known for Les Fleurs du Mal, a compilation of poems about death, sex, decay, hedonistic excess, and finding beauty in the darker parts of human existence.

De Profundis is an extension of the same theme, finding beauty in death. In a telling bit of symbolism that would have Freud salivating, Serge Lutens’ strange backstory for the fragrance includes the line: “Clearly, Death is a Woman.” Oh dear. The rest of the story, as provided by Fragrantica, isn’t any cheerier:

When death steals into our midst, its breath flutters through the black crepe of mourning, nips at funeral wreaths and crucifixes, and ripples through the gladiola, chrysanthemums and dahlias.

If they end up in garlands in the Holy Land or the Galapagos Islands or on flower floats at the Annual Nice Carnival, so much the better!

What if the hearse were taking the deceased, surrounded by abundant flourish, to a final resting place in France, and leading altar boys, priest, undertaker, beadle and gravediggers to some sort of celebration where they could indulge gleefully in vice? Now that would be divine!In French, the words beauty, war, religion, fear, life and death are all feminine, while challenge, combat, art, love, courage, suicide and vertigo remain within the realm of the masculine.

Clearly, Death is a Woman. Her absence imposes a strange state of widowhood. Yet beauty cannot reach fulfilment without crime.

Hard as it may be to believe, De Profundis’ backstory is (in my opinion) almost joyful, relatively speaking, as compared to that of La Fille de Berlin. Contrary to some people’s belief, that fragrance has nothing to do with Marlene Dietrich or the decadent excesses of Weimar Germany. When I was writing my review right before Valentine’s Day, and during my research, I stumbled upon a YouTube video in which Serge Lutens read the story behind the fragrance. I also found a brief interview he gave to the New York Times. The two things made abundantly clear that La Fille de Berlin was focused on the struggles of a German woman or women in Soviet-occupied, post-war Berlin. It is a story that is filled with implications of rape and, even, perhaps murder, to the point that I can’t really bear the perfume itself, even to this day.

At the time, I couldn’t help but wonder, “Who is this man?!” Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, the bleak backstory about the beauty of Death for De Profundis, and now, rape by Soviet occupiers, the transformation “of murder into a masterpiece,” and a woman’s lips covered by “the blood of Siegfried”?

Now, however, with all the things which I have learnt and which are discussed in Part I of this series, now, I get it. It’s about survival through the very worst of human suffering, through the greatest of all pain, even through the most traumatic aspects of war. It’s about the triumph of survival. And, ultimately, it’s about his triumph, and that of his mother (with her own wartime experiences) as well.

This ability to take the wounds of the past and see them as something more positive is reflected in his comments to The Independent in the interview discussed in Part I:

In one breath Lutens states, “You have to create your own happiness, we are the key to our own happiness,” while in the next he says, “It’s very dangerous to believe in such a cliché”. What he means, of course, is that happiness should not be confused with material wealth, beauty or success. “Even if society thinks you’re a mistake, you need to come to terms with it,” he says without sadness. “Maybe be happy about it, rejoice. Sing it as a song, clothe it, perfume it and close it to yourself.”

Serge Lutens has certainly clothed his past in perfume, and used it as a source of happiness. Yet, you may be surprised to learn that he does not actually see himself as a perfumer at all. According to the FAQ section of his website, he sees himself merely as a storyteller whose fairytales or fables are expressed through flowers and wood.

It is a process that takes time, and one whose inspiration often lies at the junction of “scent and memory.” He elaborated on both issues for The Independent:

“Sometimes it takes 12-17 years [to create a new perfume],” he says. “Sometimes it takes one year – that is the minimum – and then I will say that’s it. Then I’m not interested any more, I’ve said what I had to say.”

Although the inspiration for each creation comes from a different source, Lutens believes that through his work he is “trying to determine an identity, find a new language”. He shares his philosophy of scent and memory that underpins all his work: “It is an exercise of the memory, of your sensitivity. By the time you turn seven, this is what we call in French the reasonable age, you are going to, so to speak, record 750,000 odours in a box. Your nose is not made by these fragrances, but is there to assess whether you like, or you love, or you hate. These odours are going to create an interlace of paths going in all directions. From these odours you’re going to smell millions more, and only say ‘I love’ when you recognise something, not discover something. What you can recognise is nothing else but yourself. So around this [identity] I am trying to make the perfume recognisable. If I am using wood I want the perfume to smell like wood.”

Indeed, wood marks the beginning of Lutens’ fragrance journey. In the past he has attributed his first trip to Marrakech in 1968 as his moment of epiphany. At a small wood-workers’ studio in the souk he found a piece of cedar, “a quite attractive and a captivating type of wood; tasty, very sweet but also musky”. So overwhelmed was he by the scent that Lutens knew he had to make a perfume from it.

The impact of Morocco on Lutens went far beyond the mere appreciation for cedar. The country, its history, and its culture have become the source of much of his perfume inspiration. A good chunk of the Lutens line is oriental, after all, with clear references to the Middle East. Yet, Morocco has also become something more. It’s become this very solitary, lonely man’s sanctuary, his peaceful haven, and the place where he purposefully goes into self-imposed exile for much of the year. In my research into Lutens’ life, I stumbled upon a detailed photo series of his stunning, elaborate villa in Marrakesh, and, honestly, if it were my home, I’d probably never leave either!

The site, Kontraplan, features a photo-series called Casbah Confidential that shows Serge Lutens’ hideaway. I was so completely staggered by the sight of various rooms, I decided to include a few of them below. In order to give full credit to the site, all photos have the Kontraplan link embedded within, so clicking on them will take you to their article:

It’s quite something, isn’t it? Can you blame me for straying from the issue of perfumery? And can you imagine living in such Oriental opulence?! (On a side note, I wouldn’t be surprised if that militaristic room played some inspirational role in his development of either Sarrasins or Cuir Mauresque!) But we should return to the topic of actual perfumery.

In the FAQ section of his website, Serge Lutens shares a few of his thoughts on everything from the question of whether perfume can be an aphrodisiac, the issue of “unisex” in perfumery, and the purpose of fragrance. Please accept my apologies in advance for the wonkiness in the formatting, as the Lutens code and WordPress’ system seemed to be at war for much of the time. (And HTML coding is not my thing!)

- What is your current philosophy with regard to perfume?

- Perfume resides at the very heart of us. It is a means of self-expression. It is the dot on our “I”, a way of contemplating ourselves and sensing who we really are. It is also, in some ways, a weapon which seduces more by consequence than design. Perfume exists in the first person.

- Do you think that perfume can have an aphrodisiac effect on the people around us? What makes a perfume seductive?

- To be precise, there’s no such thing as an aphrodisiac perfume only aphrodisiac people. Wearing perfume doesn’t make you seductive. Being seductive is the result of being alive; being loved for who we are is what is important and not trying to be someone else!

- What is your opinion of unisex perfumes?

- Ask the perfume what sex it is. Who knows if an oak is male or female, or whether a rose is a he or a she? A watch is made for telling the time, isn’t it? It doesn’t matter whether it’s large or small, so long as you can read the face clearly so that you’re on time for a date! Are there CDs for men and CDs for women?! Absurd! Perfume is a product aimed at the senses not a particular gender.

- What are your favourite perfumes? Are they the most successful ones?

- The only favourite I have is the one I’m working on at any given time. It’s impossible to choose. Some of them marked the start of a new period, such as Féminité du bois which introduced the theme of “identity”, or Ambre sultan, which was the point of departure for my Arab period. Those two perfumes obviously made an impact but, as far as I’m concerned, they’re just as important in this respect as Serge noire or De profundis. They create short circuits and express emotions through fragrance. They serve as reference points or “repères” in French (notice how that word contains the word “père” or father). What interests me is going further, not into the perfume, but deeper into myself, exploring my innermost depths to extract darkness from light, and make it just as visible. [Emphasis added.]

- What perfumes do you hate? What ones do you wear and why?

If I hate a perfume, it is only because of the person wearing it, whom I either can’t stand or who makes me feel that we inhabit different worlds and that it would be impossible for us to find any common ground! I could love the most ordinary or revolting perfume if it were worn by someone I found attractive! Personally, I rarely wear perfume and, when I do – and I do so advisedly – I wear Cuir mauresque, applied liberally so you can tell what I’m wearing. I go for this one as much because of its name as because of its fragrance, which is a leathery scent, like Cordoba leather tanned over acacia. [Emphasis added.]

As a side note, I recall reading somewhere that his choice of perfume is not Cuir Mauresque, but Serge Noire. It is one of the more challenging perfumes from his export line, in my opinion, and a fragrance that reportedly took ten years to create. I can see the fragrance suiting him because, for me, Serge Noire is the story of a phoenix with a two-sided, almost Janus-like duality. And, as this peek into his history may show, Serge Lutens is definitely a phoenix in some ways. Still, if he wears Cuir Mauresque, I’m even more glad as it is one of my absolute favorite fragrances from his line. It is a scent that I think oozes classic sex appeal, a fragrance that would suit Ava Gardner, just as much as the man who began his career by celebrating female beauty at places like Vogue and Dior.

The contradiction in his personal perfume choices matches the contradiction within the man himself. The interview in The Independent emphasizes more than a few times that Lutens can be, as they put it, “contrary”:

On the one hand, he talks dispassionately, almost disparagingly, about people who declare their work a passion, but then declares that if he did not create he would die. To him, the message is important, the medium only secondary: “The passion of fragrance does not exist. You go inside something, you’re pulled to something you can’t resist despite yourself. But that’s not a passion for a fragrance; it would be ridiculous to call it that.”

Or take his view that perfume should be “inaccessible.” It is a philosophy that Lutens seems to have intentionally tried to render concrete in the most literal, geographic, physical sense possible: you can’t get to his Salons directly from the street, but, instead, you have to enter from the gardens of the Palais Royal. The Independent article has more on the issue of inaccessibility, the concomitant aspect of exclusivity, and the paradoxes within Lutens’ view:

[His store’s] inaccessible location was apparently chosen by Lutens to “attract a clientele of connoisseurs, not casual customers”. […][¶]

Originally sold only through the Palais du Royal, his creations are now slightly more widely available, with selected stockists including specialist perfumery Les Senteurs and Harvey Nichols. The complexity of the blends, the narrative behind each scent and the formulation of cosmetic means that this is a brand that appeals to aesthetes. “Perfume is just molecules,” he says in his contradictory way. “The best perfume-maker was the wind, rivers and pollens…”

Lutens does not believe perfume should be accessible, nor that it should be worn every day. To him, if you wear perfume, “you are giving yourself arms, weapons. Transforming a weakness into a strength, protecting yourself by making a stand. This is the main purpose of my perfumes – strengthening your inner self”. Indeed, he explains that he only wears his own fragrance of choice, Cuir Mauresque, very rarely: “I wear it because it makes me feel good on this particular day”.

His philosophy of “perfume as weaponry” differs vastly from my own views of the purpose or nature of perfumery, but I’m fascinated by the psychological layers behind it. And, ultimately, I’m even more fascinated than I originally was by the man himself.

In the past, I set out to systematically answer the question — “Who is this man?!” — by exploring the side of “Uncle Serge” that he’s shown in his olfactory creations. This new journey into his biographical past has been a further attempt to understand the man whom I admire and respect like few others in the perfume world. Nonetheless, I always knew one could determine only the tip of the iceberg, and little else, from second-hand accounts. Even so, this journey has left me simultaneously more perplexed, more awed, more confused, more illuminated, more impressed, and more at a loss of what to make of Monsieur Lutens than I was before.

Perhaps that is how it should be. Genius is complicated. Visionaries can be contradictory, and their core essence sometimes elusive. Serge Lutens is a quiet, complex, unbelievably talented, utterly brilliant man with a painful past, a vast range of interests, an enormously inquisitive intellectual mind, and a unique creative vision. One can’t neatly tie up such a man in a well-ordered package, and stick a bow on him. If his perfumes show anything, it is an infinite capacity for metamorphosis, and more layers than an onion. In that, and in their sophisticated, multi-faceted, sometimes difficult, contrary nature, they are the ultimate representation of the man behind their invention.

So, perhaps the best one can do in trying to decipher the enigma that is Serge Lutens is to remember that his olfactory art is really a search for identity, an identity he himself does not always understand:

“I don’t know what I am really, but by creating my own weapons and talking about them I provide them to you. Some people are going to recognise my fears. I do not want to be recognised or famous, I don’t really care about having my name in big letters, the point is to recognise who you are. All I’m talking about is identity – that is all I’ve been talking about my whole life.”

[UPDATE: you can read my exclusive interview with Serge Lutens here in which he talks more about his intellectual interests, his artistic loves, his philosophy, and his aesthetic approach to perfumery.]

Serge Lutens Profile – Part I: His Childhood, His Early Years & What Drives Him

A lonely man, born in war, unwanted by many in his family from the time of his birth, whose very existence was considered to be “a problem” and who later went on to revolutionize the worlds of fashion, beauty, photography, and perfumery. It is the story of a visionary called Serge Lutens.

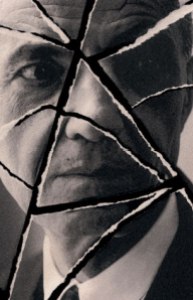

“Solitude has hard teeth.” – Serge Lutens. Photo taken in Morocco by Ling Fei. Source: Le Monde Magazine. http://www.lemonde.fr/style/portfolio/2012/05/11/la-vie-en-images-de-serge-lutens_1699467_1575563.html

He may be the darling of the perfume world now, just as he was once the rising young star in both the fashion and beauty industry, but Serge Lutens’ origins are shrouded in some mystery. It is surprising, for even though he is, by all accounts, an intensely private man, he is also an incredibly famous one. In fact, his accomplishments from the 1980s to today are so well known that I found it unusual that there was rarely much talk about his early years or his background, especially on a personal level.

His official biography on the Lutens website wasn’t much help in terms of such details, so I was utterly stunned to find an article, tucked away in the absolute bowels of the site, in which Monsieur Lutens talked about his childhood and his family. The article is entitled “Serge Lutens: Conversation” by Pierre Lescure for the RM Exhibition in France (hereinafter referred to just as the “Lescure article“), and it explains so much about the man who we know and love today as “Uncle Serge.” That Lescure piece was the impetus for me to dig deeper into the famous legend, his past, and what drives him.

I ended up discovering more than I had expected, including the extent of his difficult childhood, the scars he bears, his genius and his accomplishments, but also many things about his philosophy to perfumery. So, this will be a two-part series with Part I focusing on Serge Lutens’ background and biography: his childhood, early years, and the events that have shaped him. Part II will focus on perfumery and his philosophy towards it. It will cover such things as, for example, his views on whether perfumes are aphrodisiacs, what he thinks about fragrances being unisex, and how his creations are, ultimately, the search for his own identity.

I’ve always been a die-hard admirer of Serge Lutens, but I was rather awed by all I learnt, as well as a little heartbroken for him. I hope you enjoy the story of the solitary visionary who brushed off his painful origins and persevered like a triumphant Sisyphus to take the worlds of beauty, art, photography, and perfumery by storm, before transforming them all forever.

THE MAN & HIS LIFE:

Serge Lutens was born during WWII, on March 14th, 1942 in Lille, in northern France. He was not wanted, at least not by his father or his grandparents. In fact, it seems the tiny baby was born from adultery which is something that makes absolutely no difference today, but it did back then, especially in Pétain’s Vichy France where women (but not men) could be severely punished under the law. In the Lescure article, Serge Lutens’ painful childhood is laid bare — and it’s not easy to read:

Serge Lutens was wanted by his mother. But she was the only one who wanted him. His father didn’t want her to keep the baby. The grandparents wanted nothing to do with “this woman” for their son. But she stood her ground, despite Serge’s father, despite a new husband, despite Pétain’s law that targeted women for adultery. A courageous mother, liberated in fact, despite her lowly station in life, despite everything.

Soon after his birth, at just a few weeks of age, baby Serge was removed from his mother, and put into what would be the first of several foster care homes. That fact is borne out not only by the official biography on the Lutens website, but also by a 2013 interview with the British newspaper, The Independent, entitled “Master perfumer Serge Lutens: ‘I don’t want to be recognised or famous‘.”

There, the famously shy Lutens opens up a little about his difficult childhood and how “the lack of a maternal figure had a profound effect on him.”

“I was born in the midst of the Second World War,” he says. “At the time, my mother was married and it was a complex situation. She was unfaithful to her husband.”

“My dad is not German,” he jokes. “Let me just be clear about that. But my mum had to give me up because if she hadn’t, the laws at the time meant she would have been punished as an adulteress. She did it in order to protect me and protect herself. My mum didn’t abandon me, but it means that I didn’t see her that much and I didn’t have a motherly character in my life. My personality was influenced by that.”

Lutens has spoken previously of his “blurred identity”, partly influenced by his illegitimacy. It is a subject that he has only spoken of in a veiled way before, but in person he shrugs it off. “It’s just a normal story,” he says. “All these things are seen through the light of your own experience.”

“All my life I went from one foster family to another, and this great instability provided a great opportunity for me to be able to work on myself, to write life in a way that wasn’t planned originally.”

Despite being constantly shuttled around, and the loss of a real home or mother figure, it would seem that the very young Lutens did see his mother on occasion as a toddler. According to, the Lescure interview with Monsieur Lutens, it might have been more of an on-and-off-again thing in the early years, perhaps due to a mother’s natural fear for her baby during the terrifying time of war and Nazi occupation.

At the very least, he saw her on one occasion in 1943, in an incident he recounted to Pierre Lescure and whose painful, traumatic memories have even been rendered concrete in the architectural structure of his Paris headquarters today:

At the center of the boutique gallery, anchored in the floor, at the heart of the Royal Palace, is a massive spiral stairway that seems to spin into infinity. It takes us up to the floor. The deep, intimate, violent and artistic relationship Serge Lutens had with his mother was forced in a stairwell in Northern France in 1943 under a Nazi bombardment. “There was a warning siren. I can still see my mother’s empty eyes — empty of everything but fear. For me and for herself. We go down to a bomb shelter. I’m very small, but the memory is very precise. Everyone squeezes together. And I literally lose my mother. I am squashed by grownups. At the all-clear, I see myself being jostled and bumped, climbing this interminable rusty staircase, hanging onto the honeycomb-like surface of each step. We found each other, but the terrifying vertigo of the stairway for me is the loss of my mother.

Serge Lutens may have been only a year old or 18-months at the time of that event in 1943, but it clearly left a mark. (For those of you who wonder about how a child so young may have such a detailed memory of an incident, there are apparently some studies from child psychologists and neurologists on “event memory,” which claim that toddlers can indeed recall deep trauma, even if they can’t verbalize it at the time. I’m am wholly unqualified to speak on either issue, and am merely quoting Lutens’ comments to the interviewer.)

Whatever the precise nature of his memories, I think the issue of his mother is the key to understanding Serge Lutens. As the Lescure article makes clear, it is the context for everything that drives him:

Serge Lutens’s discoveries since the early 60’s have become historic land-marks in womens’ beauty and womens’ lives. “In this woman’s life,” Serge insists. He hates when you talk about women. That says it all. For him, it’s “this woman,” his own double, whom he reinvents in every photograph, dress, makeup, makeup design, or perfume.

And “this woman” is really just his mother. As Pierre Lescure emphasizes throughout the article, Serge Lutens’ mother is his ultimate muse and source of creativity. He is never far from her, mentally and emotionally, and has always sought to keep her near. In a moment of philosophical and Freudian symbolism, Monsieur Lutens told the journalist, “I invented her so I could exist.” She is the one whom he is ultimately and symbolically always capturing — regardless of medium, whether it is photography, makeup, fashion, or perfumery. Thus, he, “whom his father always more or less intentionally melded with his mother” has now explicitly and defiantly melded himself with her.

According to Lescure, “[t]hese fragile beginnings, the solitary path, the double life, he and she makes him a sort of anti-Lagerfeld.” Which may explain, in part, why the fashion visionary to whom Lutens feels most connected is Yves St. Laurent. “Like Yves, Lutens ‘started as a problem.'” And like St. Laurent, Lutens worked incredibly hard from an extremely young age to start on his road to success.

In 1956, at the age of 14, Lutens was sent off to work “at a bourgeois hair salon in [Lille, in] northern France.” He hated it. The official biography on his website states,

he was given a job against his will – he would have preferred being an actor – in a beauty salon in his native city.

Two years later, he had already established the feminine hallmarks that he would make his own: eye shadow, ethereally beautiful skin, short hair plastered down. He also became known for the colour black, from which he never deviated. He confirmed his tastes and his choices with the female friends of his whom he photographed.

There, in that beauty salon, the teenage apprentice hair-dresser absorbed everything like a sponge, and took photographs all the while. To quote from the Lescure piece:

He observes authentic versus fake elegance, learns how to do everything, and how to adapt everything. Like an extension of his arm and his eye, his simple little camera is always with him.

War, unfortunately, had not finished with Serge Lutens. This was France in the late 1950s, after all, and the Algerian war was raging on. It was a conflict which I studied quite a bit at one time, and you cannot begin to imagine its impact on France. It was a war that threatened to ignite the country into a civil war, and there was almost a military coup which sought to topple the French government. Like all young men, Serge Lutens was subject to national military service; in 1960, at the age of 18, he was called up. The crucible of violence had its impact, and when his one-year period of conscription was over, Serge Lutens decided to forever change his life. Around 1961 or so, he left his hometown of Lille, and made his way to Paris.

Helped by a friend, and carrying large photos that he had taken with his tiny camera, Serge Lutens sought to make it big in the capitol. It wasn’t easy at first; the official bio on his website states, elliptically and obliquely, that he experienced a time of “insecurity and need.” Then, in 1962, at the age of 20, he contacted Vogue. “For him, this magazine represented the essence of beauty: a sort of convent that he mythologised.” And, thanks to those photos and his little Instamatic that he had taken everywhere with him while working as a teenager in Lille, he got the attention of Vogue’s legendary Editor-in-Chief, Edmonde Charles Roux. To quote from the Lescure piece:

His Instamatic would wind up opening some of the very best doors. He comes to Paris in ’62. He is 20. He brings his photographs to the great Edmond [sic] Charles Roux’s Vogue, at Place du Palais Bourbon. At Elle, the […] very young Lutens would be called upon whenever there was an emergency: a photo, the perfect jewelry to complete a shoot, the Christmas edition going to press in 3 days… Quick, quick, Serge, we need an idea! The man in black would become indispensable.

A 2012 article on the Lutens’ website entitled Mysteries of Beauty by Karim Moucharik for Dalia Air Magazine elaborates further:

At the age of 20, he entered French Vogue – whose editor-in-chief was then academician Edmonde Charles- Roux – with a portfolio in hand. He contributed to it as a photographer, along with great names like Guy Bourdin, Richard Avedon or Helmut Newton.

Actually, the young Lutens was such an instant star, that he worked with everyone, not just Vogue. All the magazines came calling, from Elle to Jardin des Modes and Harper’s Bazaar. He collaborated with the most famous photographers, while also pursuing his own art. It wasn’t just Richard Avedon, Guy Bourdin, or Helmut Newton, but also Bob Richardson, the great Irving Penn, and every other photo legend.

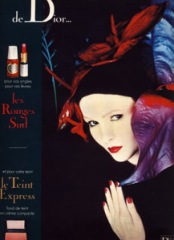

Serge Lutens wasn’t done yet. There were new worlds to conquer, and he did so when Christian Dior came calling. It was 1968, and though Serge Lutens was very young, his genius and versatility were clear to all. So, when one of the most prestigious fashion houses of all time decided that they wanted to expand into a new venture called “make-up,” they entrusted it to a 26-year old photographer and hairdresser.

Yes, it is Serge Lutens who is responsible for the invention of fashion house “makeup” as we know it today. He had already created such a buzz that, as the Lescure article makes clear, Dior and the legendary Mark Bohan turned over their entire plan “to ‘create’ make-up,” along with the development of an entire range of products, to Paris’ young, new star. Ironically, despite his love of black and his insistence on wearing nothing but black like his other heroes, Chanel and St. Laurent, Lutens would be most successful in white. According to the Lescure piece, it was the use of that unexpected colour in makeup which made the Lutens line so revolutionary. The result was a blockbuster hit, for the both of them, and a life of “Travel, luxury, airplanes, Rolls-Royces.”

In the 1970s, Lutens continued his meteoric rise. The famous editor-in-chief of American Vogue, Diana Vreeland, was unstinting in her enthusiasm and put his face on Vogue’s cover with the headline: “Serge Lutens, Revolution of Make-up!” To quote his official bio on the Lutens website, “His success was resounding. Serge Lutens became the symbol of the freedom created through makeup, for a whole new generation.”

It still wasn’t enough. Lutens started to explore different artistic ventures, and succeeded brilliantly each and every time. In 1972, according to Wikipedia, his series of photographs (inspired by such famous painters as Claude Monet, Georges-Pierre Seurat, Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani) was impressive enough to be shown at the prestigious Guggenheim Museum in New York. In 1974, he made several short films based on his passion for movies and the legendary actresses in them. They were good enough to get shown at the famous Cannes Films Festival.

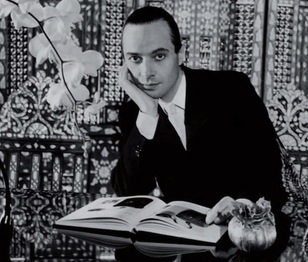

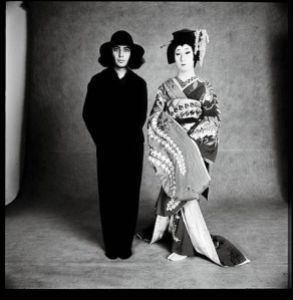

Serge Lutens 1971. Source: Serge Lutens Archives, via Le Monde style magazine. http://tinyurl.com/qj2hke6

During this time, he also travelled widely, especially to Morocco and Japan, two countries whose very different cultures would impact him enormously in years to come.

The 1980s mark the start of the period in Lutens’ life which most people know about today. It was the beginning of his Shiseido era. As his official biography explains:

in 1980, […] he signed on with Shiseido for a collaboration that was to enable the Japanese cosmetics group, until then unknown on the international scene, to establish such a powerful visual identity that it became one of the world’s leading market players in the 1980’s and ‘90’s.

Lutens created makeup for the company, designed its packaging, took photographs, and sought to reinvented Shiseido’s entire image, while also expanding their business into foreign markets. It is all thanks to Serge Lutens that Shiseido, today, is a market force and beauty giant. However, his success wasn’t limited just to beauty, marketing, and business development. Throughout the 1980s, he also shot various advertising campaigns and films for Shiseido. He was so brilliant, he won two ‘Lions d’Or‘ at the International Advertising Film Festival.

All these conquered worlds, but it still wasn’t enough for the versatile, seemingly restless genius. Lutens now decided to venture out to explore a totally new area of beauty and art: perfume. He became Shiseido’s Master-Perfumer, and released their first fragrance. Everyone has heard about his famous 1992 creation, Feminité du Bois, for the company, but what some people don’t realise is that the very first Lutens fragrance actually came a whole decade earlier. To quote his website biography, in 1982, “he conceived Nombre Noir, his first perfume, dressed in lustrous black on matte black, a concept that foreshadowed the ubiquitous codes of the 1990’s.”

Nombre Noir was a masterpiece, according to all who spoke about it to the Independent for their Lutens profile (linked up above):

[It] “burnt a hole into everyone’s collective memory”, according to Chandler Burr, former New York Times perfume critic, in his book The Emperor of Scent, which chronicles the work of ‘nose’ Luca Turin. Turin, for his part, classifies Nombre Noir “just too wonderful for words, one of the five great perfumes of the world”. No longer in production, but still a favourite among fragrance-lovers, a 60ml bottle is listed on eBay for $999 (£614) at the time of writing.

In 1992, Serge Lutens established his perfume headquarters at Les Salons du Palais Royal, but he was still working under Shiseido’s umbrella. Then, in 2000, with Shiseido’s financial backing and blessing, he went independent and launched his own, eponymous, niche brand. In all cases, however, whether it was perfume for Shiseido or creations for his own house, the effect was the same: he revolutionized the field of perfumery just as he had done decades before in beauty. By 2007, the range, depth, and impact of his decades-long work across various artistic platforms resulted in Serge Lutens being awarded the title “Commandeur des Arts et Lettres” by the French government.

In 1992, Serge Lutens established his perfume headquarters at Les Salons du Palais Royal, but he was still working under Shiseido’s umbrella. Then, in 2000, with Shiseido’s financial backing and blessing, he went independent and launched his own, eponymous, niche brand. In all cases, however, whether it was perfume for Shiseido or creations for his own house, the effect was the same: he revolutionized the field of perfumery just as he had done decades before in beauty. By 2007, the range, depth, and impact of his decades-long work across various artistic platforms resulted in Serge Lutens being awarded the title “Commandeur des Arts et Lettres” by the French government.

No matter which world he conquered, the emotional truth seems to be that he did so not for all women (plural), but always just for “‘this woman‘.” According to Pierre Lescure, Serge Lutens hates it when people talk about “women’s lives,” and corrects them to talk about “this” woman, singular. And that abstract, unnamed, representative, singular woman really seems to be one, very real, flesh-and-blood woman: his mother. Everything he has done seems to be in homage to her, in an attempt to symbolically meld himself, through different artistic mediums, to the one woman from whose arms he was ripped away in infancy. It is all for her, a woman “of great silences” who told him at some unstated, undetermined time: “‘Now it’s your turn. You must go on without me.'”

No matter which world he conquered, the emotional truth seems to be that he did so not for all women (plural), but always just for “‘this woman‘.” According to Pierre Lescure, Serge Lutens hates it when people talk about “women’s lives,” and corrects them to talk about “this” woman, singular. And that abstract, unnamed, representative, singular woman really seems to be one, very real, flesh-and-blood woman: his mother. Everything he has done seems to be in homage to her, in an attempt to symbolically meld himself, through different artistic mediums, to the one woman from whose arms he was ripped away in infancy. It is all for her, a woman “of great silences” who told him at some unstated, undetermined time: “‘Now it’s your turn. You must go on without me.'”

I’m not a psychologist, but it’s hard to escape the feeling that Freud would have had a field day by Serge Lutens’ symbolic attempts to return to his mother’s womb through the exploration of every possible artistic medium concerning women. Even that great spiral staircase in Les Palais Royale has Freudian meaning, particularly in light of Serge Lutens’ stairwell trauma that night back in 1943. Please don’t think I’m making judgments; I am not. We all bear childhood scars, but some of us have suffered more than others. And, frankly, my heart goes out to Monsieur Lutens for what clearly seems to be an emotionally devastating childhood.

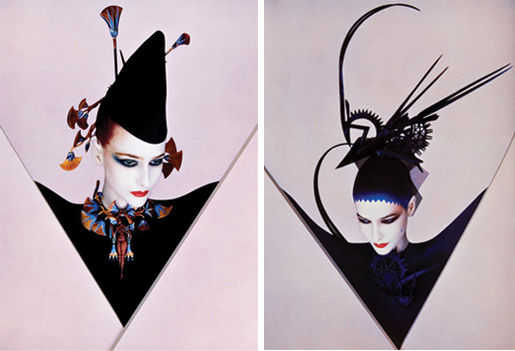

Whatever the past or the source of his inspiration, there is no doubt that Serge Lutens’ artistic homage to the famous abstract “woman,” singular, results in work that is absolutely stunning. From the Shiseido ads of the 1990s that reference modern art (and Dada-ism), to his stylistic endeavours and marketing, he has a style that is incredibly powerful, eye-catching and provocative. Take a look, for example, at some of his work in the 2012 Dalia Air Magazine piece hidden in the bowels of the Lutens website, the photos shown on the website of the French newspaper, Le Monde, or any of the Shiseido ads easily found on the web:

Whatever the past or the source of his inspiration, there is no doubt that Serge Lutens’ artistic homage to the famous abstract “woman,” singular, results in work that is absolutely stunning. From the Shiseido ads of the 1990s that reference modern art (and Dada-ism), to his stylistic endeavours and marketing, he has a style that is incredibly powerful, eye-catching and provocative. Take a look, for example, at some of his work in the 2012 Dalia Air Magazine piece hidden in the bowels of the Lutens website, the photos shown on the website of the French newspaper, Le Monde, or any of the Shiseido ads easily found on the web:

CONCLUSION:

We are all shaped by our past and, as Thomas Hardy once wrote in Tess of the d’Urbervilles, “experience is as to intensity and not as to duration.” Serge Lutens began his life in war and emotional trauma, but he used those experiences as a wellspring from which to draw strength and to overcome all obstacles. A prodigy and genius, he took the beauty and fashion world by storm, changing their face forever, before eventually setting his sights on the world of perfumery. In Part II, we will explore that world and his fragrance philosophy.