Marlene Dietrich

“The Agony and the Ecstasy.” I had heard so much about Tubereuse Criminelle, but the Perfume Shrine’s reference to the Irving Stone classic in the context of sadomasochism and Marlene Dietrich made me sit up just a little bit higher and pay strict attention. Elena Vosnaki, the award-winning editor and expert behind The Perfume Shrine, wrote about “fire and ice” and described T/C as “felonious,” before concluding: “Like Marlen Dietrich’s name according to Jean Cocteau, but in reverse, Tubéreuse Criminelle starts with a whip stroke, ends with a caress. For sadomasochists and people appreciative of The Agony and The Ecstasy. A masterpiece!!” (Emphasis added.)

Good Lord! My jaw dropped. I had to try it, and I had to try it immediately. Like any self-respecting tuberose lover, I own (and love) Fracas, created in 1948 by Robert Piguet and now, the benchmark for all tuberose scents. But perfumistas of all stripes — regardless of how they feel about classique tuberose fragrances — are also aware that today’s modern masters have sought to take tuberose and flip it upside its head. To transform it from the powerhouse legend that so many adore and that a small portion tremble before in abject horror and fear. Serge Lutens was the very first to do that in 1999 with Tubereuse Criminelle, followed thereafter by Frederic Malle in 2005 with Carnal Flower.

The Perfume Shrine’s review, along with that of numerous others, made me determined to try both modern takes on my beloved Fracas right away. (Plus, the “ice” part sounded bloody good to one suffering the horrors of a Texas summer.)

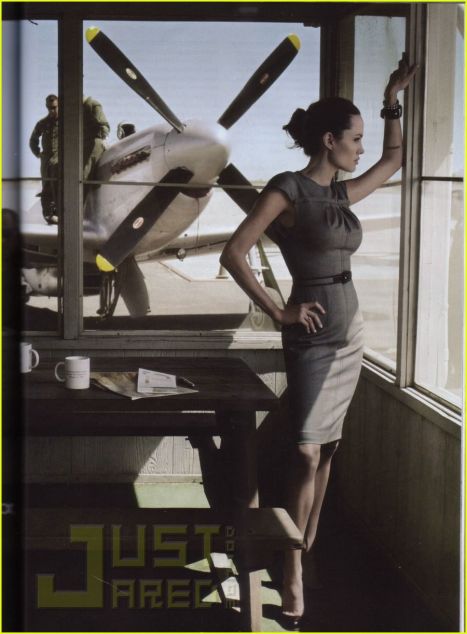

Marlene Dietrich’s legendary legs, once insured by Lloyds of London.

I did my best to overlook the numerous references to “mouth wash,” “gasoline,” “Drano,” and metholated rubber. I focused instead on “sadomasochism” and “The Agony and the Ecstasy” (a book I’d loved and a movie that isn’t bad either). Or other comments like, “criminally genius,” “subversive” and “transformative” (the latter usually said by those who previously felt ill at the mere thought of tuberose.) But, really, it was the Perfume Shrine’s review. Would you pass up the chance to feel “felonious”or to be like Marlene Dietrich cracking a whip?

While waiting impatiently for my sample bottles to arrive, I read up on Tubereuse Criminelle. Uncle Serge (as he is often affectionately called) worked with his favorite perfumer, Christopher Sheldrake, and their final product was exclusive to their Palais Royal store in Paris.

The bell jar of Tubereuse Criminelle.

It was one of the famous “bell jar” fragrances — a reference to the shape of the bottle. As a Palais Royal exclusive, it was also not available for export and was considerably more expensive than the regular, export Lutens line. (In the US, the Lutens website currently offers the bell-jar form for $300 for 75 ml or 2.5 fl. oz in eau de parfum form. However, it also offers the regular 1.7 oz/50 ml rectangular bottle for $140.)

Being one of Lutens’ “non-export” Paris exclusives just added to the mystique but, finally, in mid-2011, Lutens agreed to export the scent world-wide. Allegedly, Tubéreuse Criminelle was reformulated to comply with certain export regulations and was weakened in strength. There is no official confirmation of that; perfume houses rarely admit it. So, thus far, it is merely anecdotal references based on people’s experiences with the original Palais Royal salon perfume. But there have been a lot of those anecdotes with regard to several Lutens perfumes that are now available as exports.

I think a 2011 interview with Serge Lutens makes it pretty clear that some Lutens fragrances have definitely been reformulated for one reason or another. In an interview with Fragrantica, Lutens was asked explicitly about whether he had ever reformulated a scent to comply with those bloody IFRA regulations.

Serge Lutens

He answered as follows:

Laws are a force from which one cannot escape. They are even applied hypocritically, through the circumventing of them or, as with all the world of perfumery (if it wants to be in compliance with these laws), by replacing the forbidden with other elements… which will themselves be prohibited a few months later. However, I do not like to retrogress: what’s done is done, and it is not certain that a perfumery such as mine can continue in the future. (Emphasis added.)

The Tubereuse Criminelle entry on the Lutens website states simply:

“Les Fleurs du Mal,” Charles Baudelaire.

“Baudelaire was right. Let’s give the flowers back to evil.”

And I think he and Christopher Sheldrake achieved that to a large extent, via the ingredients. The notes for Tubéreuse Criminelle are:

jasmine, orange blossom, hyacinth, tuberose, nutmeg, clove, styrax (also known as benzoin), musk and vanilla.

But the transformative key to Tubéreuse Criminelle — the thing which made it so revolutionary as a tuberose perfume — is menthyl salicylate which is a natural organic compound found in tuberose. It creates a very medicinal, almost mentholated or camphorous eucalyptus smell that evokes “Vicks Vapor Rub” for some, but minty mouth wash for others. It can also create varying impressions of gasoline/petrol, rubbery or leather.

Tubéreuse Criminelle opens with a burst of sweet jasmine and, yes, eucalyptus and menthol. It is a much sweeter opening than I recall from when I first tried this scent this summer. Perhaps the heat amplified the menthol notes then but, today, all I smell is heady, narcotic, luxurious, sweet jasmine and, then, only in second place, the menthol. There is a muscle rub smell that is not, on me, Vick’s Vapor Rub but an almost sugared, sweetened version of Tiger’s Balm. The faintly medicinal edge is much softer than I had remembered but, at no time, has it ever been that burst of ice that I read about in the Perfume Shrine’s review. The narcotic-like headiness and warmth of the jasmine round out the notes far too much for them to be a blast of chilly ice. It is, as one person on Basenotes noted so aptly, ” “a lively cooling sharpness.”

A faintly rubbery note soon emerges. It’s not burnt rubber, but an almost thick, viscous, rubbery richness that is oddly sweet. Indolic flowers can often have a rubbery element to the narcotic richness at their heart; and this perfume contains two of the most indolic flowers around – jasmine and tuberose. (You can read more about Indoles and Indolic scents at the Glossary.) Yet, the cool freshness of menthol that cuts through the heady fumes of the flowers in a really clever way, reducing any potential cloying, over-ripeness. I am really enjoying the extremely unusual, novel, unique smell.

Perhaps that’s because I don’t smell many of the terrible notes that Tubéreuse Criminelle’s detractors repeat so frequently. Some of the comments from the negative reviews on Basenotes include the following:

- A fur coat in mothballs, wrapped in plastic. Shag carpet recently steamed with an industrial strength cleaner and still wet. The open-casket funeral of a wealthy great-aunt. Wow.

- Starts out with a strong note of iodine followed by the sharp rubber scent of brand new steel belted radial tires. […] Smells like I’m in the tire store one minute and then in a hospital testing lab the next.

- I love tuberose…but not when it’s mixed with Denorex coal tar shampoo. [..] I don’t want someone to catch a whiff of my expensive perfume and assume that I have a severe dandruff problem!!

- It smells like hot asphalt, antiseptic, rubbing alcohol, and tuberose.

- first contact- menthol, toilet bowl cleaner, fake flowers- cannot get my nose far enough away from my wrists.

- performance art more than perfume.

For the sake of balance, I should point out that Basenotes has 5 negative reviews, 7 neutral ones, and 23 very positive ones. I’m relieved that I smell few of those things that so plague the negative reviewers — or, at least, not to any comparable degree. (And I most definitely do not smell asphalt or grandma’s mothballs!) I do, however, completely understand the comparison to brand new tires. It’s extremely faint on me, but it is there. And I like the smell as a whole. I definitely consider it to be a work of genius, especially intellectual, and I enjoy certain aspects of it a lot. I’m just not sure I would reach for it, let alone frequently.

The genius of Tubéreuse Criminelle is that it has essentially deconstructed the tuberose flower down to its molecular essence, then separated those notes, and put them all together as individual prisms that — somehow — manage to make the whole even more intense than the original flower. Apparently, there is an organic compound called menthyl salicylate in tuberose (as well as some other plants) which is the basis for oil of wintergreen. So, in short, tuberose naturally produced a medicated wintergreen note, albeit a subtle one. Given that tuberose is also considered to have a very rubbery element to its heart, it’s clear that Lutens and Sheldrake have intentionally sought to emphasize the individual components of tuberose.

The perfume is, thus, like a shattered prism where each broken piece is then put back together to create an even richer, but slightly “off”, sum total. A good example of this is the opening where I smell jasmine and a few other notes, but no actual tuberose. None! At least, no tuberose the way it is in scents like Fracas, Michael Kors by Michael Kors, and most other white flower scents. I smell all the separate and individual components of tuberose, but not the flower itself. That comes later.

After the first 30 minutes, the menthol recedes, and the tuberose emerges along with a definite touch of orange blossom. After another hour, Tubéreuse Criminelle is all soft, creamy and (to my nose) heavenly tuberose. There are hints of hyacinth and lingering traces of the jasmine, but any alleged Marlene Dietrich-like black whip has now turned into the gentle caress of white flowers.

The duration of Tubéreuse Criminelle and the shortness of each developmental phase is much worse on me that it seems to be on others. On my skin, that revolutionary, hugely contradictory and very “off” opening of heady narcotic flowers and wintergreen soon fades. I think Uncle Serge simply does not design florals for my perfume-consuming skin chemistry. An hour and a half in, Tubéreuse Criminelle is white flowers with mere touch of what was once much, much more forceful “lively coolness.” I hear varying reports of just how long those opening notes last on people; those who despise the perfume obviously feels it lasts an eternity, while those who love it lament its short death. All I know is that the perfume’s truly metholated opening lasted only about 20-30 minutes on me. The first full 1 to 1.5 hours on me, it was a mix of faint wintery coolines and heady flowers. Then it became pure white flowers (with the hyacinth becoming much more dominant) and a faint touch of vanilla from the styrax/benzoin.

One type of the styrax tree which creates the resin used in Tubereuse Criminelle.

In terms of sillage or projection, it’s quite impressive at first. Tubéreuse Criminelle only started to fade about 2 hours in, which is a hell of a lot more than what I can say for Serge Lutens’ A La Nuit. I would place T/C closer to Serge Noire in terms of sillage and longevity on me, than to some of his other perfumes. Tubéreuse Criminelle became close to the skin about 3.5 hours in, which is again impressive for a Lutens, in my experience. And the whole thing lasted about 5.5 to 6 hours on me.

The best way I can really sum up my personal Tubéreuse Criminelle experience is in photos. I expected it to evoke this:

Claudia Schiffer for Vogue.

And I expected to respond like this:

Naomi Campbell by Steven Meisel.

Instead, it opened for just a short 20 minutes like this:

before turning much more into this:

And, by the end, I felt like this:

There is nothing wrong with any of that. In fact, it makes Tubéreuse Criminelle a much more approachable tuberose scent for those who previously feared anything to do with the flower.

I think that I’m absolutely in awe of the genius behind Tubéreuse Criminelle’s almost avant-garde deconstruction of the underlying flower and of its prismatic construction. Intellectually, the theory behind this makes me adore it. In real life, and for actual wearing… not so much. Beyond the sheer brilliance of its creation, it’s intriguing, yes, and there is something about that opening which makes it stay in at the back of your mind. But, ultimately and in its final moments, it’s really not all that interesting. If I owned a bottle, I’d wear it — on occasion. I simply can’t see myself reaching for it like a drug addict in need of his one pure solace.

I see nothing about fire and ice, I see no dominatrixes (not even in those first 20 minutes), and I certainly don’t see Marlene Dietrich with a whip. (Oddly, however, I actually could see her wearing this on occasion, but it wouldn’t be the first scent that came to mind when thinking about that legendary icon.) In some ways, I feel almost offended by the comparison to Les Fleurs du Mal. Baudelaire is one of my favorite poets and he would scoff at the Lutens’ website line of “let’s give the flowers back to evil” after smelling Tubéreuse Criminelle. There is nothing evil about the perfume — not the way it is on my skin. Metholated white flowers don’t arise to the level of almost malevolently decaying inner rot; and there is too much sweetness, warmth and light with the jasmine, hyacinth and the other notes. But Tubéreuse Criminelle is revolutionary. And it is also complete genius.

This review is for my brave friend, Teri, who is always an explorer of the senses and who foolhardily buys $300 Bell Jars without even a review!