Everyone knows of Coco Chanel as a fashion icon and style pioneer. She is justly respected for her vision, brilliance, and the way she changed the world of fashion. Yet, hardly anyone talks about the other side of the mirror, the Chanel who was the epitome of a cold opportunist, and an amoral, ethically challenged survivor who would claw her way to the top. If that meant — quite literally — sleeping with the enemy, then so be it. Even if that enemy was a Nazi. In fact, not only did Coco Chanel have a high-ranking Nazi lover before and after WWII, she was allegedly also a Nazi spy herself, code-named “Westminster.”

The whitewashing of history is a sore subject for me, and the case of Coco Chanel, in particular, has bothered me for a long time. Then, a few weeks ago over the recent Christmas holidays, I watched a French film about Chanel’s alleged affair with the famed composer, Igor Stravinsky, in 1920. “Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky” is a gorgeous but problematic account for a few reasons, not the least of which is whether or not there was an actual affair. (Coco Chanel insisted it occurred, Stravinsky’s main lover and second wife insisted that it did not.) Regardless, the story reminded me of the Chanel that so few talk about, the real Gabrielle Chanel, and it brought back all my old feelings.

I won’t get into the details of Chanel’s extremely difficult childhood, or the well-worn territory of her rise to power through the assistance of various lovers. Both periods of time have been amply discussed. I concede here and now, explicitly, that childhood traumas can shape us, determine our character, and are important in discussing a person’s motivations as an adult. Again, I repeat, I concede that point fully.

However, I firmly believe that there are lines, lines which cannot be excused by one’s opportunistic hungers or by an ingrained desire to survive. For me, Gabrielle Chanel crossed those lines, badly, and the cultish worship of Chanel as a fashion icon, woman and person needs to stop. There needs to be a more balanced, considered, and critical approach that takes into consideration the two faces of Gabrielle Chanel, a woman who I think resembles Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray.

The primary focus for the following discussion will be a book called Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War by Hal Vaughn. Mr. Vaughn (who passed away three months ago) was a former diplomat who was also involved with the CIA before he became a journalist. His book was released in 2011, relies heavily on recently declassified French and German documents, and garnered many rave reviews.

The issue of Coco Chanel’s anti-Semitism and war-time collaboration with the Nazis is widely known, though rarely discussed, but the book went much further than that. Based on those newly released documents, Vaughn revealed that Chanel was a Nazi spy. Yes, an actual spy. With a code-name referencing her British lover, the Duke of Westminster, who was another notorious anti-Semite.

PRE-WAR CHANEL:

A New York Times‘ book review on Sleeping with the Enemy provides a succinct chronological background to Chanel’s actions at the end of the 1920s, actions that lay the groundwork for some of the events that were to come to pass:

As her personal fortunes rose [in the late 1920s], she turned her attention to making serious inroads into British high society, befriending Winston Churchill and the Prince of Wales and becoming, most notably, the mistress of the Duke of Westminster, Hugh Richard Arthur Grosvenor (known as Bendor), reputedly the wealthiest man in England.

Bendor’s — and Chanel’s — anti-Semitism was vociferous and well documented; the pro-Nazi sensibilities of the Duke of Windsor and many in his circle have long been noted, too. All this, it appears, made the society of the British upper crust particularly appealing to Chanel. As Vaughan notes, after she was lured by a million-dollar fee to spend a few weeks in Hollywood in 1930 — Samuel Goldwyn, he writes, “did his best to keep Jews away from Chanel” — she found herself compelled to run straight back to England, so that she could wash away her brush with vulgarity in “a bath of nobility.” [Emphasis to names added by me.]

Coco Chanel wasn’t turned into an anti-Semite by her ducal lover. Many sources, including Vaughn, argue that her bigotry had deep roots, going back to her childhood at a convent where such views seemed commonplace amongst the nuns and villagers. What was more significant about the Duke of Westminster, the richest man in England and her lover for 6 years, was that he introduced Chanel to Winston Churchill. They became life-long friends, and it was a friendship that would serve her well when the time came down the road. In the meantime, she was living it up in Paris and was one of the wealthiest women in the world, thanks, in part, to the runaway success of Chanel No. 5.

A little known fact is that Coco Chanel had Jewish partners, Pierre and Paul Wertheimer, whose descendents now control the entire Chanel empire. (As a result, the modern-day Wertheimer brothers are billionaires, with a combined net worth of over $19 billion dollars.) Chanel may have been an anti-Semite, but she was an opportunist first and foremost — and she badly needed the Wertheimer brothers in order to make her perfumes a success. I’ll rely on Pierre’s Wikipedia entry for the basic background details, though I’m fully aware that Wikipedia often has serious flaws and should only be used as a starting point in things. Still, the brothers aren’t the focus of this piece, and the Wikipedia account is supported by a site called Funding Universe. So, back to the Wertheimers. In the early 1920s, the two brothers were very wealthy, thanks to their father who founded the French makeup company, Bourjois. (It is still the cheaper arm for Chanel cosmetics to this day.)

In 1924, Chanel sought their financial backing in order to launch her perfume line and, most specifically, Chanel No. 5. In essence, the Wertheimers acted as venture capitalists in a new corporate entity called “Parfums Chanel,” in return for a whopping percentage of the rights and profits. As the Wikipedia entry explains:

In 1924, Coco Chanel made an agreement with the Wertheimers creating a corporate entity, “Parfums Chanel.”

Chanel believed that the time was opportune to extend the sale of her fragrance Chanel No. 5. to a wider customer base. Since its introduction it had been available only as an exclusive offering to an elite clientele in her boutique. Cognizant of the Wertheimer’s proven expertise in commerce, their familiarity with the American marketplace, and resources of capital, Chanel felt a business alliance with them would be fortuitous. Théophile Bader, founder of the Paris department store, Galeries Lafayette, had been instrumental in brokering the business connection by introducing Pierre Wertheimer to Chanel at the Longchamps races in 1922. […]

For a seventy percent share of the company, the Wertheimers agreed to provide full financing for production, marketing and distribution of Chanel No. 5. Théophile Bader was given a twenty percent share. For ten percent of the stock, Chanel licensed her name to “Parfums Chanel” and removed herself from involvement in all business operations.[4] Ultimately displeased with the arrangement, Chanel worked for more than twenty years to gain full control of “Parfums Chanel.” In 1935, Chanel instigated a lawsuit against the Wertheimers, which proved unsuccessful.[5]

Then, war came, and oh, what an opportunity it was for Mademoiselle Chanel. Up to that time, she had been living the high-life in a luxurious apartment at the Paris Ritz Hotel. While that part of her life didn’t change when the Nazis goose-stepped their way up the Champs-Elysees, they brought with them the convenient benefit of Aryanization laws that would target Jewish-owned business.

THE NAZIS & CHANEL:

“Chanel, age 56, photographed by George Hoyningen-Heune, 1939 (copyright Horst/ Courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery).” Source: Newyorksocialdiary.com

To quote a New Republic book review called “The Stench of Perfume“:

While her fellow countrymen starved and died, she lived like a queen in the Ritz, surrounded by Nazi officers and enjoying Nazi parties. Berlin ordered that the Ritz was “reserved exclusively for the temporary accommodation of high-ranking personalities,” meaning that Chanel must have made connections with some very powerful Nazis in order to stay there. And there is the matter of her anti-Semitism.

In addition to her collaborations, Chanel spoke loudly and vehemently against Jews, and even tried to take advantage of the Nazi seizure of Jewish businesses and property. Her world-famous perfume, Chanel No. 5, was owned and produced by the Wertheimers—a rich Franco-Jewish family. Chanel had always been paranoid that the Wertheimers were stealing from her (though her lawyer assured her of the contrary), and during the war, when the family had fled to America, she attempted to take full control of Chanel No. 5. But the Wertheimers had anticipated that the Nazis (or Chanel) might try to steal their company, and therefore they signed it over to a Frenchman for the duration of the war. Chanel couldn’t touch it. The Wertheimers also sent a spy, Herbert Gregory Thomas (under the pseudonym, Don Armando Guevaray Sotto Mayor), to retrieve the chemical formula to make Chanel No. 5 as well as collect all the necessary ingredients. He then brought everything back with him to America, so that the Wertheimers could continue to produce and sell the fragrance.

Chanel may have been thwarted in her attempts to use Nazi Aryanization laws to obtain control of the perfume company that bore her name, but the Nazis still made her rich. Very, very rich. The blog, MessyNessyChic, explains:

On May 5, 1941, Coco Chanel wrote to the government department in charge of the handling of Jewish financial assets.

These are her words in the letter:

Parfums Chanel is still the property of Jews … and has been legally ‘abandoned’ by the owners. I have an indisputable right of priority. The profits that I have received from my creations since the foundation of this business…are disproportionate.

Ultimately, Chanel was awarded the wartime profits from the sale of her perfume, including share of two percent of sales which amounted to the equivalent of $25 million a year in modern currency. This made her the richest woman in the world at that time– thanks to the Nazis.

“The young Baron von Dinklage circa 1935 at the German Embassy in Paris when he was working for the Gestapo, already a close friend of Chanel.” Source: NY Social Diary. http://www.newyorksocialdiary.com/node/1907697/print

Chanel was equally successful in satisfying her voracious sexual appetites. There’s nothing wrong with that, but my disdain stems from her choice of lovers: Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage, a senior officer for the Abwehr or German Military Intelligence, who reported directly to Goebbels. Dincklage, who was much younger than Chanel, ended up being the last great love of her life.

Chanel didn’t stop at merely taking on a high-ranking Nazi lover. She became an actual Abwehr spy, with her own number: Abwehr Agent 7124. Her code name was “Westminster,” harkening back to her anti-Semitic ducal lover in England. The basis for Vaughn’s argument: those newly declassified documents from French and German authorities, as well as Nazi documents taken by the Soviets back to Russia and similarly released by that government in recent years.

Chanel and her Nazi lover sought to recruit wealthy Europeans to the Nazi cause, and Chanel had two actual missions. To be fair, some of Chanel’s wartime efforts were an attempt to secure the release of those she cared about. One mission to Madrid was done partially to secure her nephew’s release from a German POW camp. Some people try to justify her meeting in Berlin with the SS‘s intelligence chief, General Walter Schellenberg, and Himmler‘s right-hand man in the same way. (Yes, she met with Nazis who were that powerful!)

The reason for that meeting was “Modellhut” (or “model hat”). That was the codename for her second mission for the Nazis, which took place in 1943, and sought to counter the turning tide of the war by using Chanel’s friendship with Winston Churchill to achieve a peace with terms that wouldn’t hurt Germany. As a Washington Post book review of “Sleeping with the Enemy” puts it:

When Germany began to falter, the Nazis came to believe that Chanel might be useful in contacting her old friends Churchill and the Duke of Westminster and brokering a possible peace. She didn’t disappoint. She did what she was told to do and, in 1944, she wrote Churchill a letter, referring obliquely to her German connections.

[It didn’t work, but] Chanel continued to live at the Ritz, rub shoulders with Nazis and dine on poularde rotie, even as French families dug through the city’s garbage, trying to fend off starvation. […]

Parisians foraging for food, via NewYorkSocialDiary.com. http://www.newyorksocialdiary.com/node/1907697/print

As the war ground on and Dincklage came and went from Berlin, convincing his bosses that she was trustworthy, thousands of French Jews were herded to sure deaths in Poland and Eastern Europe. But the glamorous woman with the deft needle and acid tongue was safe. The good life at the Ritz continued to roll on. There were legions of women of courage and derring-do throughout Europe, working hard to outwit the Nazis. Chanel was not among them.

THE LIBERATION OF PARIS & CHANEL:

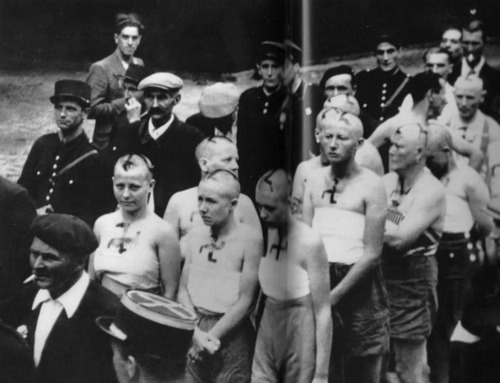

In the final days of August 1944, after Paris was liberated, retribution for the “collabos” or those who collaborated with the Germans was harsh. Some say about 30,000 to 40,000 people were executed. “Horizontal collaborators” or women who merely slept with the Germans suffered as well, though it was primarily humiliation and ostracism. The punishment was swift and brutal, even though none of them were actual Nazi spies who went to Berlin to meet with Hitler’s spy chief. An excerpt of “Sleeping with the Enemy” in the New York Times gives you a small idea of what happened:

A thirst for revenge gripped the nation in the last days of August. Four years of shame, pent-up fear, hate, and frustration erupted. Revengeful citizens roamed the streets of French cities and towns. The guilty — and many innocents — were punished as private scores were settled. Many alleged collaborators were beaten; some murdered. “Horizontal collaborators” — women and girls who were known to have slept with Germans — were dragged through the streets. A few would have the swastika branded into their flesh; many would have their heads shaved. Civilian collabos — even some physicians who had treated the Boche — were shot on sight. The lucky were jailed, to be tried later for treason.

What did Coco Chanel do? She hurriedly ran out into the streets to give bottles of Chanel No. 5 to American GIs! (You have to almost admire her nerve.) A few days later she was arrested, but Winston Churchill made a phone call, and she was soon released.

Chanel got off scot-free, and for reasons that went much further than Winston Churchill’s intervention. With the help of influential friends, including her ex-lover the Duke of Westminster, she successfully orchestrated a cover-up. She lied about pretty much everything and to everyone. She even went so far as get a former collaborative ally arrested by the French Partisans and, later, to bribe the ailing Nazi spymaster to keep her secret. To quote the New York Times review that I referenced at the start:

She tipped off the poet and anti-Nazi partisan Pierre Reverdy, a longtime occasional lover, so that he could arrange the arrest of her wartime partner in collaboration, Baron Louis de Vaufreland Piscatory; she paid off the family of the former Nazi chief of SS intelligence Gen. Walter Schellenberg when she heard that he was preparing to publish his memoirs. (It was Schellenberg who had given her the “model hat” assignment.)

Chanel and Dincklage. in 1951 at Villars sur Ollon, Canton de Vaud, Switzerland. Source: fashionatto.literatortura.com via Paris Match &

Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs, Paris, France/ Archives Charmet/ The Bridgeman Art Library

God only knows what the partisans did to a French traitor like the Baron, but it can’t have been anything good. In the meantime, mere days after her questioning and release, Chanel fled to Switzerland. There she remained for 8 years, until 1954, with her Nazi lover, living in style and in the height of luxury. Oh, and taking drugs while she was at it as well. Chanel was a hard-core morphine addict, relying on it daily until she was well into her 70s.

Throughout it all and until her death, she was coldly unapologetic for her actions, which is one of the things that bothers me the most. She may have done some things to survive, but I think she went too far, and, worst of all, she never once felt any regret.

Instead, when asked in later years about her Nazi ties, she coolly responded, “I don’t ask my lovers for their passports.” As for the French, a Portugese site, Fashionatto, quotes her as saying, “The French got what they deserved” and “Not all Germans were bad guys.” No, not all Germans were bad, and yes, the French behavior during the Vichy Government was abominable, but Chanel’s callous dismissal of the details goes a step too far. One of the things that irritates me to no end is her sheer indifference to anything other than herself. There is narcissism, and then there is megalomaniacal narcissism — I’m trying to decide there should be an entirely separate category reserved solely for Gabrielle Chanel.

As even The New York Times puts it,

Gabrielle Chanel — better known as Coco — was a wretched human being. Anti-Semitic, homophobic, social climbing, opportunistic, ridiculously snobbish and given to sins of phrase-making like “If blonde, use blue perfume,” she was addicted to morphine and actively collaborated with the Germans during the Nazi occupation of Paris. And yet, her clean, modern, kinetic designs, which brought a high-society look to low-regarded fabrics, revolutionized women’s fashion, and to this day have kept her name synonymous with the most glorious notions of French taste and élan.

CHANEL’S POST-WAR COMEBACK & THE WERTHEIMERS:

One of the strangest parts of this whole sorry tale is the behavior of the Wertheimer Brothers after the war. They paid for Chanel to live in the lap of luxury, from her exile in Switzerland until her death in Paris in 1971 at the age of 87. Their generosity boggles my mind. I can understand why they would finance her reestablishment in French society and the re-emergence of Chanel as a business success; that benefits them indirectly and financially. It was a business decision about a corporate entity. But her personal bills? All of them, and until her death? Despite her collaboration and despite how she had treated them personally? That takes the milk of human kindness to levels that I simply cannot fathom. (Yes, I am a much less forgiving person.) Meanwhile, Chanel grabbed the money, and then declared that Pierre Wertheimer was “the bandit who screwed me.”

There seems to be the suggestion that Pierre Wertheimer was a long-time admirer of Chanel, and perhaps had a crush on her, but that didn’t prevent the two of them from having a little perfume war while Coco was in exile. There is a site called Funding Universe which has a detailed history of Chanel and her company, and which talks about the conflict over “Parfums Chanel“:

[After the war ended,] Pierre Wertheimer returned to Paris to resume control of his family’s holdings. Despite her absence, Coco Chanel continued her assault on her former admirer and began manufacturing her own line of perfumes. Feeling that Coco Chanel was infringing on Parfums Chanel’s business, Pierre Wertheimer wanted to protect his legal rights, but wished to avoid a court battle, and so, in 1947, he settled the dispute with Coco Chanel, giving her $400,000 and agreeing to pay her a 2 percent royalty on all Chanel products. He also gave her limited rights to sell her own perfumes from Switzerland.

Coco Chanel never made any more perfume after the agreement. She gave up the rights to her name in exchange for a monthly stipend from the Wertheimers. The settlement paid all of her monthly bills and kept Coco Chanel and her former lover, von Dincklage, living in relatively high style. It appeared as though aging Coco Chanel would drop out of the Chanel company saga.

At 70 years of age in 1954, Coco Chanel returned to Paris with the intent of restarting her fashion studio. She went to Pierre Wertheimer for advice and money, and he agreed to finance her plan. In return for his help, Wertheimer secured the rights to the Chanel name for all products that bore it, not just perfumes. Once more, Wertheimer’s decision paid off from a business standpoint. Coco Chanel’s fashion lines succeeded in their own right and had the net effect of boosting the perfume’s image. In the late 1950s Wertheimer bought back the 20 percent of the company owned by Bader. Thus, when Coco Chanel died in 1971 at the age of 87, the Wertheimers owned the entire Parfums Chanel operation, including all rights to the Chanel name.

Pierre Wertheimer died six years before Coco Chanel passed away, putting an end to an intriguing and curious relationship of which Parfums Chanel was just one, albeit pivotal, dynamic. Coco Chanel’s attorney, Rene de Chambrun, described the relationship as one based on a businessman’s passion for a woman who felt exploited by him. “Pierre returned to Paris full of pride and excitement [after one of his horses won the 1956 English Derby],” Chambrun recalled in Forbes. “He rushed to Coco, expecting congratulations and praise. But she refused to kiss him. She resented him, you see, all her life.”

There is an interesting interview with the author of “Sleeping with the Enemy” in The New Yorker, where he answers some questions about the Wertheimers, talks about Chanel’s return from exile, and why there is so little discussion about Chanel’s past.

[Q.] As your title makes clear, the book emphasizes Coco Chanel’s wartime life. Why has this story not received much attention over the years?

I have no idea. I can’t figure it out. Either people didn’t want to know or chose not to deal with it. Of course, this story will not please the Wertheimers, one of the richest families in the world. Other than that, I have no idea why not.

[Q.] After the war, Chanel moved to Switzerland. How was it possible that she would ever be able to reëstablish herself in France, as she did in the mid-nineteen-fifties?

The simple answer is Wertheimer money: Chanel was backed by the Wertheimers. But really there was also the fact that, by 1954, most French people didn’t give a damn about who collaborated and who didn’t. De Gaulle had decided that all Frenchmen had been resisters, and all this collaboration business was behind them. And let’s not forget that Chanel was also tremendously talented.

[Q.] After everything Chanel had done to Paul Wertheimer, why did he ultimately agree to finance the reëstablishment of her couture house in 1954? And why did he consent to pay all her expenses—large and small—for the rest of her life?

From the point of view of the Wertheimers, the decision was extremely logical. What they were doing is not buying a business but rather an empire for a lifetime, and indeed that’s what it’s been. Here we are in 2011—can you go to any major city without seeing a Chanel store? It’s the unique mark in the world today.

[Q.] Especially in France—a nation still grappling with the legacy of collaboration—how is it possible that the Chanel brand today bears almost none of the stigma assigned to other brands often associated with Nazi complicity

The work of Robert Paxton never quite rubbed off on our memory of Chanel—and for a simple reason. She is essentially a hard-currency machine. Chanel is an icon, an idol in France—never mind the details of her life, her anti-Semitism, her dealings with the Nazis. Interestingly enough, I should mention that the French have not bought my book—at least not yet. It’s coming out in America and in Britain and in Germany. It’s been translated in Portuguese and translated into Dutch. But the French have yet to buy the book.

[Q.] Given Coco Chanel’s wartime past, what do you make of the prominence and popularity of the Chanel brand today? Should anyone still wear Chanel?

I have no feelings against Chanel. You can’t put someone like Klaus Barbie and Chanel in the same category: she didn’t kill anybody; she didn’t torture anybody. Madame Gabrielle Labrunie—Chanel’s grand-niece—said something to me that I found fascinating. She said to me: “You know, Mr. Vaughan, these were very difficult times, and people had to do very terrible things to get along.” Chanel was, very simply put, an enormous opportunist who did what she had to do to get along. [Format “Q.” insertions added by me for sake of clarity.]

I very much agree with him. I think the primary, driving characteristic of Gabrielle Chanel was opportunism, followed closely by a ruthless hunger to succeed at any or all costs. She was petty, avaricious (she was reported to be notorious for not paying her seamstresses as much as others, and treating them harshly), narcissistic, coolly calculating, and pragmatic. In my opinion, if she had her heart set on something (or someone’s husband), she would stop at nothing to get her way. She would sup with the devil, if need be, and she would do it all without a second thought.

The same thing applies to the consequences for that behavior. If she could get away with something, she would do everything to ensure it, no matter what the cost to others. And Chanel never seems to have paid for anything. By 1954, she undoubtedly realised that passions had cooled and a prosecution would be too risky. Too many unpleasant truths would come out about too many powerful people. Far better to drop it all, and pretend that none of it had happened, much as the French did for other dirty memories of those years. By the 1960s, she was dressing the wife of the French President, Madame Pompidou, and re-emerging as a success.

Yes, she was an anti-Semite, but she never seemed to let that get in the way of making money or climbing the social ladder. That is one reason why I laugh at the company’s attempted defense of Chanel. They weakly offer the “Jewish friends” argument, whimpering that she would not have ties to the Rothschilds or some Jewish friends if she were really an anti-Semite. The Rothschilds, the legendary and supremely, galactically wealthy Rothschilds?! Of course she would be their friend! Good God, Chanel would probably have peed in public while standing on her head if the Rothschilds had asked her to. That doesn’t mean that she wasn’t a bigot. I personally happen to believe that she did agree with a number of Nazi beliefs. The idea of a “super man” would very much fit how she saw herself, as well as her snobbish disdain for anyone without power, money, lineage, or some combination thereof. As a whole, though, I think Chanel’s only real, unwavering belief was in the currency and religion of Coco Almighty. Does that excuse her actions? Hardly.

Two things need to be stated clearly. First, there are very few people alive today who are in a position to truly judge the situation of those wartime years. I did not go through the utter hell that was Nazi occupation, and I cannot know what I would do if I were in Chanel’s shoes. War and desperation can make us do terrible things. I recognize all that, and yet, I can never forgive Gabrielle Chanel her actions. Whenever I read people gushing over her admittedly exquisite taste, her glamourous life, and her luxurious apartments, I think about who she used, slept with, or betrayed. When people talk admiringly about her strong-willed passions and how fabulous she was, I grit my teeth. When people swoon over her exciting love affairs (e.g., a Romanov Imperial Grand Duke, among others), I think instead of her Nazi lover. I simply cannot get past what a vile and loathsome human being she really was.

Second, I want to preempt what is the inevitable response to all this: “genius can be terrible, but it’s still genius.” It is what I call the “Wagner Argument,” and often takes the subtext of “They were a genius, so it’s okay. We can excuse it, or still enjoy their accomplishments.” Perhaps, but I don’t think it’s actually okay. What I want is a more critical, balanced perspective of Gabrielle Chanel that doesn’t white-wash or excuse her. In short, I want the blind, whole-sale, positively cult-like worship of Gabrielle the woman to stop, even if people continue to enjoy the products or things that she achieved. And yes, I don’t think there is anything wrong with buying something with the name “Chanel” on it.

For me, the corporate entity that exists today has nothing to do with Gabrielle Chanel, and hasn’t in decades. That is one reason why I will never stop reviewing her perfumes or buying Chanel products. Certainly, “Parfums Chanel” was largely owned by everyone but Chanel since 1924. She had a mere 10% stake in the company from its birth, and lost even that after the war. Furthermore, she never made a single perfume herself after 1947; the Wertheimers did. Chanel is a multi-billion conglomerate that capitalizes on the personal mystique and legend of Gabrielle Chanel, and they would be foolish not to. It’s only business, as they say.

Nonetheless, the next time you admire something about Chanel, the woman and person, I hope you will remember the other side of the mirror. She was Janus, with one face that reflected a fashion and stylistic trailblazer, a pioneer whose achievements in those particular, narrow fields has to be terribly admired. I certainly do — enormously. But the Roman god, Janus, also has a second face. In the case of Gabrielle Chanel, it rather resembles Dorian Grey’s portrait in the attic: maggot-ridden, venal, ulcerous, oozing internal decay, and thoroughly diseased with amorality, cruelty, corruption, and the blackest of ethics.