1899 is the year of Ernest Hemingway‘s birth, and also the name of the newest fragrance from Histoires de Parfums, a French niche perfume house founded by Gérald Ghislain. It is a company whose perfumes are often entitled simply with a date in history, the year in which a legendary figure was born. This fall, they tackled Ernest Hemingway. I absolutely loathe the man for his personal life and character, but I was intrigued by how his essence might be encapsulated on an olfactory level. So when I saw a bottle of 1899 while visiting Jovoy Paris, I eagerly tested it on paper. My initial impression was far from favorable, but scented strips rarely tell an accurate tale, so I asked for a sample. I thought things might change upon a proper test. They did not, in large part. While I now see more to 1899 Ernest Hemingway than I did then, I’m still not particularly enthused.

1899 is the creation of Gérard Ghislain, and is an eau de parfum. Histoires de Parfums’ full description for the scent, along with its notes, is as follows:

The top notes of Italian bergamot, juniper and pepper are intended to be the aperitif that sparks the conversation and awakens the palate in anticipation of the meal. Following “Papa” from Spain to Italy with Mediterranean scents that evaporate to leave place to a darker mood, where the amber and vetiver mixed is reminiscent of the waxed wood of a Cuban bar top. The exotic meets the familiar, the tropical heat is cooled off by a glass of scotch.

Top Note: Italian bergamot, juniper, black pepper

Heart Note: Orange blossom, Florentine Iris, Cinnamon

Base Note: Vanilla, Vetiver, amber

1899 Hemingway opens on my skin with a cocktail of salty sea crispness and hesperidic citrus freshness. First and foremost is juniper, yielding a green, pungent, pine-y, very outdoorsy aroma. It is infused with fruits, perhaps from actual juniper berries themselves, but also with crisp, lemony bergamot. I tested 1899 three times and, on the last occasion, juicy oranges were also quite noticeable, adding a fruited, sweet touch to juniper’s foresty, green, spicy, peppered aroma. Seconds later, black pepper, green vetiver, and a touch of floral iris join the mix.

1899 Hemingway has the initial profile of a very masculine cologne, but with greater heft and less thinness in its body. It is a profile that I struggle with, if I am honest. Juniper is not something that will make me jump up and down in ecstacy, and neither do black peppercorns or iris. Still, it’s a very rugged, outdoorsy, masculine aroma and I can see why they chose it for Hemingway.

Five minutes in, other elements become noticeable. Hints of orange blossom flit about with a slightly bitter, dark, pungent and piquant undertone that resembles neroli more than any indolic, lush, white floral bomb. In 1899’s depths, the vanilla slowly starts to stir. Up top, the vetiver becomes much more pronounced. It’s not earthy, damp, and rooty at all. Actually, when combined with the sharp, fresh citruses and the piney, almost cedar-like aroma of juniper, the vetiver feels very green. To me, the three notes together create the mineralized accord of the vetiver in Terre d’Hermès, only with a much more Alpine feel. During his first marriage, Hemingway went often to Switzerland, and there is something of that clean, fresh, crisp mountain air in 1899. You can almost see the vast forests of Switzerland before your eyes, only these are not snowy but dotted with orange and lemon trees as well.

1899 is a very well-blended fragrance that doesn’t always develop in the exact same manner. In my three tests, some of the notes varied in strength or in the order of their appearance. Take, for example, the iris. During my first test, it was barely a factor for most of 1899’s lifespan, popping up only occasionally at the perfume’s edges but without any substantial heft whatsoever. In my second test, it was quite pronounced in the end, adding a powdery touch to the perfume’s sweet final stage. In my third one, however, the iris suddenly appeared noticeably right from the start, adding its floral coolness to the Alpine meadows. Another note that seemed to vary in its character was the orange blossom which consistently seemed more fruited than floral, except the first time around when it manifested itself in both ways.

Nonetheless, 1899 does have some uniform aspects to its development. About 10 minutes in, the fragrance turns warmer and starts to lose its cologne-like sharpness. A touch of cinnamon appears, the amber awakens from its slumber, and the vanilla starts its slow rise to the surface. Warmth and sweetness slowly start to creep over 1899, like a wave inching up a sandy beach. The amber, vanilla and cinnamon may not be noticeable in any profound, individual way, but they have an indirect effect on the other notes. They make the orange blossom lose some of its piquant, bitter, neroli-like undertone, and soften the sharpness of the juniper, while adding a touch of spice. At times, the overall effect is almost like Viktor & Rolf‘s Spicebomb, but not quite.

Suddenly, 25 minutes in, the warm notes flood the surface and 1899 changes into a much different fragrance. Gone is the purely cologne-like scent with its crisp, citrus, woody, masculine profile. Now, there are oriental and floral touches. First up is the orange blossom which stops feeling purely like a ripe, juicy, sweet fruit, and more like the actual white flower. It adds a sensuous touch to Hemingway’s face, like a warm, seductive caress across his unshaved whiskers redolent of his woody, piney, vetiver, lemon aftershave. While the main note remains the peppery, spicy juniper, it’s now been infused with cinnamon and amber as well.

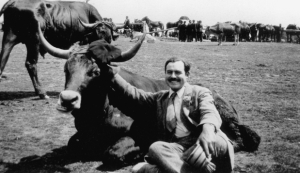

1899 Hemingway’s shift is complete at the 40-minute mark when the vanilla bursts onto the scene like a white bull running into a Pamplona arena. From Switzerland, we’ve suddenly landed in Spain where Hemingway spent so much time in the 1930s. The land of Seville oranges, orange blossoms, groves of green, dry warmth, and languid sensuality — it’s all here, under the top layer of rugged, outdoorsy juniper-lemon cologne. I know Histoires de Parfums gives the perfume’s geographic trajectory as Spain to Italy to Cuba, but I’m sticking with Switzerland to Spain, with crisp Alpine forests taking on a more Mediterranean sensual warmth. I have to say, I find the olfactory symbolism quite impressive on an intellectual level.

I just wish I liked the actual smell. For me, the opening was too much like cologne, but uninteresting cologne. The juniper was too sharp and turpentine-like at times, and didn’t even have the appeal of a gin-and-tonic. I liked even less 1899’s new combination of vanilla with crushed juniper needles, trailed closely by cinnamon, then by orange blossoms, oranges, lemons and amber. Honestly, it made me feel queasy, each and every time. Something about the combination felt cloying in its sweetness, somewhat odd in its polar opposite parts, and simply not appealing at the end of the day. Perhaps I’m simply not a fan of juniper mixed with vanilla, gooey oranges, unctuous orange blossoms, and cinnamon. It is the main profile of 1899 Hemingway for hours and hours, and I really wanted it to stop.

1899 Hemingway brought to mind two other Histoires de Parfums’ scents, but for very different reasons. Like many from the line, the fragrance is not revolutionary or edgy, but has a gracefulness about it — regardless of whether you like the notes or not. Like its siblings, 1899 is potent at the start, while also being incredibly airy in weight and very well blended. In that way, it resembles Ambre 114. Yet, at its core, 1899 is thematically quite close to 1725 Casanova in its transition from masculine to soft, unisex, and almost gourmand in nature. It’s that powerful vanillic base that both fragrances share, after a very crisp start. However, 1899 is significantly more masculine in my opinion, even at its end, thanks to the woody juniper. 1725 Casanova is smoother, more truly unisex with its lavender, more gourmand at its base, and much better balanced in my opinion. It never felt cloying, or a war of extreme, opposite notes.

That brings me to what may be my fundamental issue with 1899 Hemingway: it doesn’t know who it wants to be. It took me a while (and three tests) to suddenly realise that the perfume is trying to be all things to all people. It straddles so many different genres: masculine cologne, oriental, woody outdoorsy, gourmand, and many hybrid versions thereof. But it can’t seem to make up its mind. I don’t have a problem with the fact that Histoires de Parfums has made a fragrance with a commercial, mainstream character — some people on Fragrantica think that 1899 is like Spicebomb — but I struggle with the perfume’s fragmented, confused identity. Perhaps that makes it very Hemingway after all; the writer was known to be a complex set of contradictions with a highly insecure, sometimes utterly neurotic side. (I am trying so, so hard to be polite about the man!)

Getting back to the perfume’s development, there really isn’t a lot more to say. Until its end, 1899 remains a scent that is primarily vanilla, juniper and some form of orange (or orange blossom) infused with a hint of cinnamon, all atop an amber base. At the 1.5 hour mark, its sillage drops, the perfume feels thinner, its edges blur, and the notes are not easily separable in a distinct, individual way. Three hours in, 1899 hovers just barely atop the skin. The sillage isn’t impressive as a whole with 1899 unless you apply a lot. Eventually, 1899 Hemingway fades away in some sort of sweetness and with an average lifespan of about 7.5 hours.

“Shades of Leaves,” abstract photography by Bruno Paolo Benedetti. Source: http://imagesinactions.photoshelter.com/gallery-image/abstract-impressionist-photography/G0000LzIQxYEISEo/I0000rdtpLoFmVPU

The very end, however, seems to differ in terms of its olfactory specifics from wearing to wearing, perhaps as a result of the quantity applied. In one test, using 3 average sprays from the small atomizer, 1899 ended just after 7 hours in a blur of woody, juniper and vanilla. In another test, using 2 tiny sprays, it took a mere 6 hours for 1899 to die, ending in a powdery, floral, iris-y vanilla blur. In my last test, using 4 big sprays, 1899 lasted longer, just under 9 hours, before fading away with orange-y sweetness and nothing else. The atomizer’s hole is very small, so the quantity applied is probably much smaller than from an actual bottle. It would probably range between 1.5 big smears from a dab vial to about 4 very small, narrow ones.

1899 Ernest Hemingway is too new for there to be comparative reviews that I can show you. The fragrance’s Basenotes entry (on the old Huddler Archive) doesn’t have any comments from those who have tried it. Fragrantica‘s early discussion thus far seems to focus on the extent to which it is like Spicebomb. Some think it’s a much better version. One person (“deadidol“) thinks 1899 Hemingway is well-done, but largely a bore. I agree with parts of his assessment:

More often than not, this brand misses the mark for me, and Hemingway’s a bit of a snooze. When HdP step outside they box, they truly innovate, but too many of their scents strike me as pleasant, run-of-the-mill affairs that are solid value for money, but aren’t contributing anything new. This is a mildly boozy oriental with a powdery iris note and a hefty amount of spices. There are some floral undertones that are met with a dry fruit note to spin the scent as opulent, but it’s linear and doesn’t really do anything to distinguish itself from the more powdery offerings of Dior, ByKilian etc. Also, the connection to Hemingway is a total mystery as there’s nothing rugged, troublesome or even narratalogical at work here, and it’s certainly not very masculine or virile. With that said, it’s a practical addition to the line as it’s big and amiable, bearing notable similarities to Bois d’Argent, but it’s not going to have much appeal for those who are hoping for another Petroleum, Marquis de Sade, Ambrarem, or Ambre 114. Durable and great value (another one of HdP’s strong points), but ultimately too pleasant, too powdery, and too prosaic.

I think 1899 Hemingway is much more rugged and outdoorsy than he does, but I do agree that the fragrance is merely a pleasant, “run-of-the-mill” scent with some “amiable” features. Just how amiable will depend on what you think of the central juniper note, and its interaction with the vanilla and spices. It’s not my cup of tea.

Nonetheless, I have to agree with another Fragrantica commentator in giving kudos to Histoires de Parfum for avoiding the usual, traditional clichés about Hemingway. It would have been all too easy to make a fragrance centered on cigars and rum. And, in my opinion, the company has actually succeeded in encapsulating parts of Hemingway’s life and contradictory character. They’ve created a perfectly pleasant fragrance that will probably be very sexy on some men’s skin. Unfortunately, I find it hard to sum up enthusiasm for more than that.