A lot of people rely on a perfumes’s list of notes to figure out if it’s something that they’d like or even want to test out. But, sometimes, it’s not so easy. Some terms are less familiar or obvious than “rose” or “vanilla.” For example, I highly doubt the average person has ever heard of “opoponax,” let alone know what it is or smells like. As perfume houses increasingly seek the latest new thing, and as synthetic compounds continue their sharp rise in use, perfume notes are getting much more complicated to figure out at a quick glance.

We’re not all experts and we all have to start somewhere. I’m no exception to the need for some refreshers or definitions from time to time, so I thought I’d give a list of terms to help out. They will be basic, nutshell explanations with a simple description of what the ingredient is supposed to smell like. (I owe much gratitude to the experts at NST, Fragrantica and elsewhere whose explanations, knowledge and definitions I’ve learnt from and have quoted frequently below.) I will constantly update the list or add to the descriptions, so it will be a work in progress in some ways.

GLOSSARY OF TERMS:

Malaysian Agarwood.

Agarwood. (Also referred to or known as Aoud or Oud.) Agarwood is an extremely ancient element found in the East. No-one explains its heritage, characteristics and its current usage half as well as the experts at CaFleureBon, so I will just link to their marvelous, brilliant analysis of it here. To make a long story short, however, Fragrantica states that Agarwood ”is reputed to be the most expensive wood in the world” and that Oud is the “pathological secretion of the aquillaria tree, a rich, musty woody-nutty scent that is highly prized in the Middle East. In commercial perfumery it’s safe to say all ‘oud’ is a recreated synthetic note.” Its scent ranges from freshly bracing or crisply cool, to vegetal, and, in many cases, quite medicinal. Almost like bandages. (For more information on what it smells like, you can read my post on Oud fragrances.)

Aldehydes. Aldehydes are essentially organic compounds. Chanel No. 5 became famous for having the greatest percentage of aldehydes (fatty aldehydes to be specific), but almost all perfumes have it to some degree or another. On me, the smell is something intensely soapy with floral and lemony undertones. The varying definitions or explanations are either too simplistic or far too complicated (and with too much chemistry), so I’ll just rely on the best one I’ve found which is from Bois de Jasmin: “Aldehydes are organic compounds present in many natural materials (eg. orange rind, rose, cinnamon bark). Various aldehydes can also be synthesized artificially. There is hardly a fragrance without some type of aldehyde in it; however, it is the vividness of aliphatic aldehydes (a specific subgroup of the aldehydes family) that gives Chanel No 5, Lanvin Arpège, Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche and other floral-aldehydic fragrances their characteristic impressionist sparkle. Their scent ranges from metallic, starchy and citrusy to green, fatty and waxy (for instance, aldehyde C-11 commonly found in rose and cilantro smells like metal and dirty hair to me, but in tiny quantities it adds an impressive lift and freshness to fragrances.) […]Chanel No 5 became famous for its unprecedented overdose of several different aldehydes (a total of almost 1%.)” Common descriptions of aldehydes range from: “a champagne-like, sparkly, fizzy odor that makes the fragrance fly off the skin” to a waxy, citrusy or rosy aroma, like snuffed-out candles” — but it’s usually a bit more complicated than that. (See, Perfume Shrine, here.)

Ambergris. Essentially, sperm whale vomit. No, I’m not joking. NST explains as  follows: “Ambergris: a sperm whale secretion. Sperm whales produce it to protect their stomachs from the beaks of the cuttlefish they swallow. Ambergris was traditionally used as a fixative, but in modern perfumery, ambergris is usually of synthetic origin (including the synthetic compounds ambrox, ambroxan (see), amberlyn). Ambergris is described as having a sweet, woody odor. Today, the term “ambergris” is used nearly interchangeably with ‘amber.’” To replace natural ambergris, a synthetic compound was created called Ambroxan.

follows: “Ambergris: a sperm whale secretion. Sperm whales produce it to protect their stomachs from the beaks of the cuttlefish they swallow. Ambergris was traditionally used as a fixative, but in modern perfumery, ambergris is usually of synthetic origin (including the synthetic compounds ambrox, ambroxan (see), amberlyn). Ambergris is described as having a sweet, woody odor. Today, the term “ambergris” is used nearly interchangeably with ‘amber.’” To replace natural ambergris, a synthetic compound was created called Ambroxan.

Ambroxan. A synthetic compound created to replace Ambergris. (See above.)

Aoud. (See Oud below or read my post on Oud fragrances.)

Aromatic Fougère. (See also, Fougère.) “Aromatic Fougère” isn’t an ingredient but a sub-set of the Fougère category of perfumes. To quote Wikipedia, fougère “is one of the main families into which modern perfumes are classified. […] The class of fragrances have the basic accord with a top-note of lavender and base-notes of oakmoss and coumarin. Aromatic fougère, a derivative of this class, contains additional notes of herbs, spice and/or wood.”

Artemisia Absinthium

Artemesia. (Also known as Wormwood.) Acording to NST, Artmesia refers to a “category of diverse family of plants, so named because at one time they were used to prepare worming medicine. The latin name is artemisia, and in perfumery, wormwood and/or artemisia often refers specifically to artemisia absinthium, one of the key ingredients of Absinthe.” Artemesia is supposed to smell pungent, extremely green, sharp and bitter. Some say it smells like tarragon concentrated to the umpteenth degree. It is said to bring down the cloying nature of some notes, like civet, but it can also be extremely pungent by itself. Basenote commentators say that it acts like a filter to diffuse out some stronger, sweeter notes and to let you smell the more subtle ones, especially when it is used in perfumes with an oakmoss, leather and/or patchouli base. It is a strong feature in many classic scents, particularly chypre perfumes, and is one of the key characters in such scents as Robert Piguet’s Bandit, YSL’s Kouros for men, and Krizia Uomo.

Balsam. Balsam is the dark, oozing secretions from a tree that differs from “resin” mainly in terms of its form and method of preparation. When something is referred to as being Balsam-like or Balsamic, it means the scent has the aroma is like a resin which can range from sweet, amber-y and vanilla-like, to vanilla, cinnamon, though usually of a slightly woody nature. Degrees of sweetness, bitterness and/or smoke may vary depending on the type of tree that is used.

Bergamot. The smell of bergamot falls between orange and lemon, and is most closely associated with Earl Grey tea. It can turn a little woody and some people can occasionally smell hints of lavender lurking around.

Benzoin. When perfume notes list “Benzoin,” they really mean Benzoin resin. (See below) Technically and scientifically, there is a difference, since “Benzoin” is an organic compound that is not used in perfume. So, when you see “Benzoin” listed, they are really referring to a type of residue from a tree.

Benzoin Resin. (See also Styrax.) Benzoin is a type of resin and, as such, evokes the scent of amber. Depending on the type of resin, it can be both sweet and smoky, or just incense-y and slightly woody. Types of Benzoin resins are, for example, Siam Resin or Sumatra Resin. Wikipedia states the following: “Benzoin resin or styrax resin is a balsamic resin obtained from the bark of several species of trees in the genus Styrax. It is used in perfumes, some kinds of incense, as a flavoring, and medicine.” Bois de Jasmin explains further: “Benzoin has a clear vanillic fragrance (it contains vanillin, just like vanilla beans) as well as a hint of cinnamon. It is one of the most versatile notes among other balsams, and it is used in most amber, vanilla and oriental accords. It also can be found all over the fragrance wheel, from citrus colognes to woody blends. I especially love its sweet vanillic note in Chanel Coromandel and Serge Lutens Vétiver Oriental, where paired with incense, it creates a gilded, plush sensation.

The berries, buds and leaves of the Black Currant plant. Source: Perfumed Shrine.

Black Currant or Black Currant Buds. Also known as Cassis, black currant has a scent that is tarter some of its sweeter fruit companions (like plum). Depending on what parts are used, it can also come off as greener. The Perfume Shrine has a good explanation of the scent as well as the occasional tendency for some people to smell sour, almost urine-like ammoniac notes: “[c]ompared to the artificial berry bases defined as “cassis,” the natural black currant bud absolute comes off as greener and lighter with a characteristic touch of cat. Specifically the ammoniac feel of a feline’s urinary tract, controversial though that may seem. Black currant absolute comes from the bud… but also from the distilled leaves of the plant … and is extracted into a yellowish green to dark green paste that projects as a spicy-fruity-woody note retaining a fresh, yet tangy nuance, slightly phenolic.” Black currant or its buds are featured in a number of extremely popular, famous fragrances. A few examples are: Black Orchid by Tom Ford, Chamade and Champs Elysees by Guerlain, Gucci Rush II by Gucci, Escape by Clavin Klein, First by Van Cleef & Arpel, Beautiful by E.Lauder, In Love Again by YSL, Fan di Fendi by Fendi, and Rock & Rose by Valentino. (Source: Fragrantica.)

Bulgarian Rose: Bulgarian roses belong to the damask rose category which usually have a heady, richer, darker element to them than something like a tea rose or a Moroccan rose. (To my nose, at least.)

Calone. According to NST, calone is “an aroma chemical that adds a ‘sea breeze’ or marine note” to perfume. It was first used in large quantities in Aramis New West (1988). Some of the many perfumes that contain calone are: Davidoff’s Cool Water, Dior’s Dune, L’eau d’Issey, Kenzo Homme and Calvin Klein’s Escape.

Cassis. The French term for black currant. (See above.)

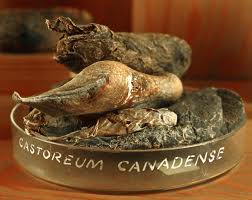

Castoreum. Castoreum is the excretion from the anal sacs of beavers. Again, I am not joking. I couldn’t possibly attempt to describe or define this one on my own, so I will  simply quote large chunks of an article on it from Beauty.About.Com: “Used by the animal during scent marking and mating, this bitter, strong-smelling, orange-brown secretion is dried, ground and put into alcohol to produce the aromatic castoreum resinoid used in perfumery. The undiluted secretion from the beaver is said

simply quote large chunks of an article on it from Beauty.About.Com: “Used by the animal during scent marking and mating, this bitter, strong-smelling, orange-brown secretion is dried, ground and put into alcohol to produce the aromatic castoreum resinoid used in perfumery. The undiluted secretion from the beaver is said  to have a perisistent, bitter and penetrating odor. In its resinoid form, as a perfume ingredient, castoreum imparts an animalistic note that approximates the scent of dried leather.” For animal cruelty reasons, I’m sure that the scent used in modern perfumes is all synthetic. If the thought of beaver anal sacs has completely put you off, you might be surprised at the list of extremely famous fragrance names which use Castoreum. In women’s perfumes: Chanel Cuir de Russie, Coty Emeraude, Lancome Magic Noire, Givenchy III, Guerlain Shalimar, Jean Patou 1000, Guerlain Jicky, Frederic Malle Une Rose, Juliette has a Gun Midnight Oud, Paloma Picasso Pure Parfum, and Robert Piguet Bandit. “A selection of men’s fragrances starring castoreum include Profumo Castoreum, Le Labo Labdanum 18, Chanel Antaeus, Amouage Epic Man, Caron Third Man, and Estee Lauder Aramis.”

to have a perisistent, bitter and penetrating odor. In its resinoid form, as a perfume ingredient, castoreum imparts an animalistic note that approximates the scent of dried leather.” For animal cruelty reasons, I’m sure that the scent used in modern perfumes is all synthetic. If the thought of beaver anal sacs has completely put you off, you might be surprised at the list of extremely famous fragrance names which use Castoreum. In women’s perfumes: Chanel Cuir de Russie, Coty Emeraude, Lancome Magic Noire, Givenchy III, Guerlain Shalimar, Jean Patou 1000, Guerlain Jicky, Frederic Malle Une Rose, Juliette has a Gun Midnight Oud, Paloma Picasso Pure Parfum, and Robert Piguet Bandit. “A selection of men’s fragrances starring castoreum include Profumo Castoreum, Le Labo Labdanum 18, Chanel Antaeus, Amouage Epic Man, Caron Third Man, and Estee Lauder Aramis.”

Chypre. Chypre is one of the main categories or families of perfumes. Chypre scents are usually (but not always) considered to be women’s fragrances. They begin with citrus top notes, have labdanum as one of their middle notes, and conclude with oakmoss (in conjunction with other ingredients) as their base. The oakmoss is key and a signature part of chypre perfumes, but the base also often includes musk or some sort of animalic note. The NST website states it best and most succinctly: “Chypre: pronounced ‘sheepra’, French for ‘Cyprus’ and first used by François Coty to describe the aromas he found on the island of Cyprus. He created a woodsy, mossy, citrusy perfume named Chypre (launched by Coty in 1917). Classic chypre fragrances generally had sparkling citrus and floral notes over a dark, earthy base of oakmoss, patchouli, woods and labdanum. Modern chypre fragrances usually use less (or no) oakmoss because of regulatory restrictions; sometimes they use synthetic substitutes.” Wikipedia adds, “Chypre perfumes fall into numerous classes according to their modifier notes, which include but are not limited to leather, florals, fruits, and amber. Modern chypre perfumes have various connotations such as floral, fruity, green, woody-aromatic, leathery, and animalic notes, but can easily be recognized by their ‘warm’ and ‘mossy-woody’ fond which contrasts the fresh citrus top, and a certain bitterness in the dry-down.” As Wikipedia notes, the basic notes usually consist of: citrus (bergamot, neroli, lemon or orange); oakmoss (woody and mossy); patchouli; and musk (sweet, powdery and animalic). The overall “composition is usually enhanced with a floral component through rose and jasmine oil.” The chypre family includes some of the most famous scents in the world, from such fruity chypres as Femme by Rochas and Mitsouko by Guerlain, to leather chypres like Bandit by Robert Piguet, floral chypres like Knowing by Estée Lauder, and green chypres like Givenchy III.

Cistus. Cistus really refers to Labdanum. The small cistus shrub is native to the  Mediterranean and Middle East, and the distillation of its leaves produces a dry resinous, faintly woody smell that is called labdanum in perfume. Essentially, labdanum is another resin like amber, but it has more of a masculine toughness to amber’s sweetness. Labdanum can be dirty, animalic and almost reminiscent of sex at times, while other compositions can bring out a more leather-like smell. It is also known as

Mediterranean and Middle East, and the distillation of its leaves produces a dry resinous, faintly woody smell that is called labdanum in perfume. Essentially, labdanum is another resin like amber, but it has more of a masculine toughness to amber’s sweetness. Labdanum can be dirty, animalic and almost reminiscent of sex at times, while other compositions can bring out a more leather-like smell. It is also known as  Rockrose. One perfumer and research scientist described it as follows on her blog, Perfume Project NW: “Some people think it smells like goat. Others think it smells like ambergris, or leather, or pine rosin, or musk. Yet others think it smells like strange, rotten fruit. Some people think it must be the smell of heaven, and others think it’s the smell from hell. Everyone seems to have a different reaction to rock rose, otherwise known as Cistus ladaniferus (also spelled ladanifer).”

Rockrose. One perfumer and research scientist described it as follows on her blog, Perfume Project NW: “Some people think it smells like goat. Others think it smells like ambergris, or leather, or pine rosin, or musk. Yet others think it smells like strange, rotten fruit. Some people think it must be the smell of heaven, and others think it’s the smell from hell. Everyone seems to have a different reaction to rock rose, otherwise known as Cistus ladaniferus (also spelled ladanifer).”

Clary Sage. Clary sage is a herbaceous plant, and not the same sort of sage that you  use in cooking. According to a helpful discussion on Basenotes, the regular sage that you use in cooking is called Dalmatian sage. A number of people find clary sage to be sweeter, fresher and with a hint of peppermint, while Dalmatian sage is more bitter, biting and aromatic. Clary sage is also said to have elements of lavender in its odor profile and, sometimes, even of green tea. Fragrantica, however, describes the plant as having a “bracing herbaceous scent that smells like lavender with leathery and amber nuances, thus very popular from old times for perfumed products.”

use in cooking. According to a helpful discussion on Basenotes, the regular sage that you use in cooking is called Dalmatian sage. A number of people find clary sage to be sweeter, fresher and with a hint of peppermint, while Dalmatian sage is more bitter, biting and aromatic. Clary sage is also said to have elements of lavender in its odor profile and, sometimes, even of green tea. Fragrantica, however, describes the plant as having a “bracing herbaceous scent that smells like lavender with leathery and amber nuances, thus very popular from old times for perfumed products.”

Coumarin. (See also, Tonka Bean.) Wikipedia states that Coumarin is a fragrant plant substance, found in many plants in the grass family and found in particularly high concentrations in the tonka bean. It goes on to explain that: “[t]he name comes from a French word, coumarou, for the tonka bean. It has a sweet odor, readily recognised as the scent of new-mown hay, and has been used in perfumes since 1882.”

Elemi. Elemi is a type of tree from the Philippines that is closely related to those which give us Frankincense and Myrrh. Surrender to Chance says: “[w]hen the leaves sprout, it exudes a natural resin that yields an oil and stops when the last leaf sprouts.” Elemi resin is pale-yellow with honey-like consistency and initially has a lemony aroma that later gives way to something that is variously described as either a nutmeg-like scent or (more commonly) to something like pine needles. It is sometimes called “the poor man’s Frankincense” because it definitely has an incense component to its aroma. The Perfume Shrine states: “The overall scent of elemi can best be typified in perfume lingo as ‘terpenic‘, an aroma typified by fresh pine needles, clean, green with citrusy and coriander undertones. It’s therefore not unusual to see it featured in the context of ‘pine’ compositions or in masculine fragrances, as well as in incense blends.” There appears to be a difference in aroma between the oil — which is more lemon-y and fresh — and the resin which is more peppery and smoky. The Perfume Shrine says: “elemi resinoid on the other hand has the spicy peppery and woody-grassy facets more pronounced making it pair perfectly with pepper, woods (patchouli and vetiver especially), and sweet grass, while its constituent elemicin is shared with nutmeg.”

Fougère. Fougère isn’t an ingredient but a category of fragrance. Fragrantica states: “Name of the olfactive group ‘fougere’ derives from French word ‘fougere’ or ‘fern’. Coumarin can be found in the center of compositions. Perfume-originator of this group is Fougere Royal by the house of Houbigant, created by Paul Parquet in 1882. The perfumer extracted the synthetic component coumarin and used it in perfumery for the first time. Coumarin can be found in nature in several plants, such as Tonka beans, and it possesses intensive scent of freshly mown grass. Fougere compositions include notes of lavender, geranium, moss and wood. This group primarily includes perfumes for men.”

Frangipani. Frangipani is also known as plumeria, a flower common to tropical climates like Mexico or South America but also to such exotic islands as Fiji, Tahiti and Hawaii. It has a very heavy, heady, lushly ripe, extremely sweet scent similar to magnolia, gardenia and tuberose. It can also bring to mind coconuts. Frangipani is often described as an “indolic” scent, meaning heady, narcotic and, sometimes, over-ripe, sometimes to the point of decay. (See entry for “Indolic.”)

Frankincense. (See also, Olbanum.) According to NST, frankincense is “a gum resin from a tree (genus Boswellia) found in Arabia and Eastern Africa. It is harvested by making an incision in the bark; the milky juice leaks out and is left to harden over a period of months before it is collected.” It smells dark, and smoky, and was often used as incense in religious ceremonies. It has some similarities to Myrrh but, to my nose, myrrh is softer and sweeter, not as sharp and dark. For a great article on the two and their history, you can go to CaFleureBon and read their analysis here. In general, however, the smell of frankincense encompasses a wide range: woody with pine and sometimes lemon undertones; sweet and nutty; thick, sticky, very dark and heavy, like an old, somewhat dusty church where a lot of incense was used; earthy, sharp, peppery and dusty; or some combination of the above.

Galbanum

Galbanum. Galbanum is a gum resin from certain Persian plant species that resemble large fennel or anise plants. The perfume site, I Smell Therefore I Am, has an excellent, extremely helpful explanation of its scent: “With its penetrating, pine-like top note and slightly bitter, woody base, galbanum makes green pop, as if one of the green chypres had slapped you hard in the face with a chunk of bundled stems. […] Part frankincense, part vetiver, its leafy terpenoid astringency ventilates the pastures of Carven’s Ma Griffe, Cellier’s Vent Vert, Ivoire de Balmain, Pheromone, Devin, Chanel No. 19 and, most spectacularly, Estee Lauder’s Aliage, which is more gale force than languid breeze. […] Galbanum is mercurial, effecting compositions in subtly different ways. It smells modern, though, along with aldehyde, it was the previous generation’s equivalent to the fruity accords which buoy contemporary florals to varying degrees and towards often vastly different ends. The smell is intensely, viscerally green, smelling of grass and aromatic weeds and herbs. It penetrates your consciousness and roots there, a vivid inhalation of the great Out There.”

Guaiac Wood – one of the hardest woods in the world.

Guaiac. Guaiac (or Guaiac Wood) is the heartwood of a Palo Santo (Bulnesia sarmienti) tree. Fragrantica states: “Odor Profile: Exotic wood note that has tar-like, phenolic facets, imparting smoky, tarmac notes.” A Basenotes commentator agrees, stating that Guaiac wood has a: “rosy, honeyed-sweet and slightly smoky and waxy-oily slightly rubbery aroma. It is used often in tobacco scents.” Another thinks it smells like “pepper and burning leaves.” In all cases, however, it differs in scent from oud or agarwood.

Immortelle. Source: The Perfume Shrine.

Immortelle. Immortelle is known by a variety of names such as “Everlasting Flower” or Helicrysum. It is sometimes even known as the “Curry plant,” though it has nothing to do with curry or the spices in it. It is a sunny, yellow plant from the Meditteranean, particularly Corsica and Italy. The Perfume Shrine describes its smell as follows: “The odour of immortelle absolute is difficult to describe, somewhat similar to sweet fenugreek and curcuma, spices used in Indian curry, with a maple-like facet. Quite logical if you think that the essence contains alpha, beta and gamma curcumene.” In addition, it also has “[r]ich scents of dry straw, dusty amber, coffee, burnt licorice, syrupy and powdery, and spices (reminiscent of celery, fenugreek and curry[.] … Like burnt sugar and dry straw combined is a suitable effort at conveying immortelle’s nuanced profile, but the more the oil warms up on the skin, the more it reveals human-like, supple nuances of honeyed notes, waxy, intimate… It pairs well in chypres and oriental fragrances, where it pairs with labdanum, clove, citruses, chamomille, lavender and rose essences.” The maple syrup comparison is repeated by the Perfume Posse who adds that the analogy “doesn´t really do the smell justice, because it´s more complex and peculiar than “maple syrup” would suggest. Here are some other common descriptions: a strong straw-like, fruity smell; straw, honey and tea; as well as words like warm, sweet, caramel, coumarin, fruit-honey, tonka. Osmoz.com says ‘essence of immortelle gives chypre, floral and amber compositions a particular charisma” and characterizes the smell as “red fruit, syrupy, nut, honey-flavored, tobacco.’ ”

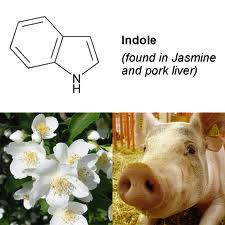

The organic Indole compound found in certain white flowers like jasmine or tuberose. And, apparently, in pork liver too!

Indolic. (Or Indoles.) Indolic is a term that is usually used to describe certain heady, rich, lush, almost creamily ripe scents. It’s most commonly associated with certain white flowers like tuberose and gardenia, though jasmine, lilac and honeysuckle are also create ver indolic scents. Bois de Jasmin explains it as follows: “Jasmine, lilac, honeysuckle, gardenia, and orange flower all have diverse olfactory profiles, yet they share the presence of indole, which gives them a rich, narcotic fragrance. Without this unique material, which in pure form looks like white diamond dust, it would have been impossible to recreate the true scent of blooming flowers. A tiny amount of indole is all it takes to infuse life into a composition of floral notes, to make an abstract, vague petally form to appear as a lush, nectar suffused flower. Indole is often described as ‘fecal and animalic,’ which is a complete misrepresentation. In its pure form, indole smells like moth balls, possessing the same heavy, sweet, tar-like pungency. In fact, it is so strong, suffocating and diffusive that smelling it pure one is hard pressed to imagine that it could be a lovely floral note. Yet, indole changes dramatically in dilutions. It suddenly displays its radiant, floral quality. The suffocating moth ball effect disappears to give way to a completely different image–a handful of gardenia petals or a branch of jasmine flowers. The opulent, narcotic effect of indole is employed whenever a perfumer wants to create a floral effect or else to give a lift to a heavy, oriental composition.”

ISO E Super. Source: Fragrantica

Iso E Super. Iso E Super is a synthetic chemical used to perfumers to boost the strength and longevity of scents. I’ve written a full post about the aromachemical, as well as the perfumes which contain it, and the potential headache-inducing aspects to the note. You can find it here. Chanel’s in-house perfumer, Jacques Polge, is one of those who loves to it, particularly to amp up florals. NST states that it’s “described by International Flavors & Fragrances as ‘Smooth, woody, amber note with a ‘velvet’ like sensation. Superb floralizer. Used to impart fullness and subtle strength to fragrances.” (Source: NST) To my nose, however, it can often be extremely peppery, antiseptic and medicinal in aroma with a strong underpinning of rubbing alcohol. Some people are completely anosmic to the scent (meaning they can’t detect it at all), while others get terrible headaches from it. It is rarely listed as an official note in perfumes but more and more fragrances nowadays have it. You can read my post for more information on it, along with a list of some of the perfumes that include the note.

Labdanum. (Also known as Labdanum Ciste or Cistus.) Labdanum comes from the small cistus shrub which is native to the Mediterranean and Middle East. The distillation of the cistus leaves produces a dry resinous, faintly woody smell that is called labdanum in perfume. Essentially, labdanum is another resin like amber, but it has more of a masculine toughness to amber’s sweetness. Labdanum can be dirty, animalic and almost reminiscent of sex at times,  while other compositions can bring out a more leather-like smell. Labdanum is also sometimes referred to as Rockrose. One perfumer and scientist described it as follows on her blog, Perfume Project NW: “Some people think it smells like goat. Others think it smells like ambergris, or leather, or pine rosin, or musk. Yet others think it smells like strange, rotten fruit. Some people think it must be the smell of heaven, and others think it’s the smell from hell. Everyone seems to have a different reaction to rock rose, otherwise known as Cistus ladaniferus (also spelled ladanifer).”

while other compositions can bring out a more leather-like smell. Labdanum is also sometimes referred to as Rockrose. One perfumer and scientist described it as follows on her blog, Perfume Project NW: “Some people think it smells like goat. Others think it smells like ambergris, or leather, or pine rosin, or musk. Yet others think it smells like strange, rotten fruit. Some people think it must be the smell of heaven, and others think it’s the smell from hell. Everyone seems to have a different reaction to rock rose, otherwise known as Cistus ladaniferus (also spelled ladanifer).”

Moroccan Rose. Moroccan roses are a type of cabbage rose and, as such, have a sweet, honey-like scent.

Myrrh. Like Frankincense, myrrh is a gum resin. It has a smoky but sweet element and, to my nose, is not as sharp or as acrid as frankincense can (occasionally) be. For a great article on the two and their history, you can go to CaFleureBon and read their analysis here. One type of myrrh used in perfumes is Opoponax. (See below.) In general, however, the smell of myrrh encompasses a wide range: resinous and sweet; medicinal and bitter; licorice or aniseed-like; incredibly soapy, cool, and white; or sharp and dusty.

Oakmoss. Oakmoss is “derived from a lichen (evernia prunastri) that grows on Oak trees. The use of real oakmoss is restricted (but not prohibited) due to regulations meant to avoid allergic reactions.” (Source: NST) One site explains the smell of this incredibly important ingredient as follows: “Oakmoss has a strong, earthy-mossy aroma. It imparts a wet forest floor scent that is very true to nature, with dry, earthy, green, and bark-like qualities, and a leather-like undertone. Oakmoss is highly valued as a fixative agent in perfumery, for its ability to anchor more volative fragrance notes, and add a rich undertone and smoothness to all perfume types (oriental, floral, chypre, etc).” Oakmoss is not only highly regulated now in terms of quantity under the IFRA regulations, but its amount may be lessened even further under additional and new regulations that are to take effect in 2013.

Olbanum otherwise known as Frankincense. (See above.) According to NST, olbanum/frankincense is “a gum resin from a tree (genus Boswellia) found in Arabia and Eastern Africa. It is harvested by making an incision in the bark; the milky juice leaks out and is left to harden over a period of months before it is collected.” It shares some similarities with Myrrh.

Opoponax. A type of myrrh that NST states is also known as “sweet myrrh” and “bisabol myrrh.” NST adds that Opoponax “has a sweet, balsam-like, lavender-like fragrance when used as incense. King Solomon supposedly regarded opoponax as one of the ‘noblest’ of all incense gums.” (Source: NST)

Oriental Fougère. Oriental Fougère is not an ingredient but a classification or category of perfume. “Fougère” is a type of aromatic perfume or cologne that has lavender, coumarin and/or oakmoss. So, an Oriental Fougère is, essentially, a fragrance that has oriental notes mixed with woody ones. (See, Fougère up above for more that category of perfume,)

Orris (or Orris root). Orris root is the root of the iris flower ,and is often used in perfume or makeup as a fixative or base. It has a richly floral, heavy scent, often evocative of violets.

Oud. (Agarwood, Aoud, or even Oudh.) Oud comes from Agarwood which is an extremely ancient element found in the East. No-one explains its heritage, characteristics and its current usage half as well as the experts at CaFleureBon, so I will just link to their marvelous, brilliant analysis of it here. To make a long story short, however, Fragrantica states that Agarwood ”is reputed to be the most expensive wood in the world” and that Oud is the “pathological secretion of the aquillaria tree, a rich, musty woody-nutty scent that is highly prized in the Middle East. In commercial perfumery it’s safe to say all ‘oud’ is a recreated synthetic note.” (For information on what it smells like, you can read my post on Oud fragrances.)

Patchouli. NST states that patchouli is “a bushy shrub originally from Malaysia and India. […] Patchouli has a musty-sweet, spicy-earthy aroma; modern patchouli is often molecularly altered to remove the musty components.” (Source: NST)

Peru Balsam. From my reading of Fragantica’s explanation, Peru balsam is a type of  wood whose essence has a cinnamon and vanilla smell. At the same time, it has a green olive base which exudes an earthier, as well as bitter, aroma. It shares some similarities with Siam Resin. (See below.) Both smell like sweet vanilla but Peru Balsam has a cinnamon aspect too, along with that earthy, bitter edge. In contrast, Siam Resin — which used to be burned as incense — is more smoky and woody. Bois de Jasmin states, in comparing Peru Balsam to Tolu Balsam: “I find Peru balsam spicier and smokier. The smoky note can be introduced by processing methods when the raw material is boiled in water over a wood-burning fire. It is quite a dark, heavy material, and it is usually blended with other balsamic and ambery notes as in Hermès Elixir des Merveilles, Serge Lutens Amber Sultan, Lorenzo Villoresi Incensi, Yves Saint Laurent Opium or Nicolaï Sacrebleu Intense.” In short, Cinnamon Vanilla with bitter green earth -vs- Sweet Vanilla with smoky, incense and wood. Tolu Balsam or Balsam of Tolu is similar to the Peru Balsam.

wood whose essence has a cinnamon and vanilla smell. At the same time, it has a green olive base which exudes an earthier, as well as bitter, aroma. It shares some similarities with Siam Resin. (See below.) Both smell like sweet vanilla but Peru Balsam has a cinnamon aspect too, along with that earthy, bitter edge. In contrast, Siam Resin — which used to be burned as incense — is more smoky and woody. Bois de Jasmin states, in comparing Peru Balsam to Tolu Balsam: “I find Peru balsam spicier and smokier. The smoky note can be introduced by processing methods when the raw material is boiled in water over a wood-burning fire. It is quite a dark, heavy material, and it is usually blended with other balsamic and ambery notes as in Hermès Elixir des Merveilles, Serge Lutens Amber Sultan, Lorenzo Villoresi Incensi, Yves Saint Laurent Opium or Nicolaï Sacrebleu Intense.” In short, Cinnamon Vanilla with bitter green earth -vs- Sweet Vanilla with smoky, incense and wood. Tolu Balsam or Balsam of Tolu is similar to the Peru Balsam.

Petitgrain. Petitgrain refers to “oil distilled from leaves and twigs of a citrus tree, usually the bitter orange tree.” (Source: NST) Essentially, it’s the slightly bitter, woody part of the orange blossom tree, and it adds a masculine touch to fragrances.

Plumeria. See Frangipani.

Resin. (See also, Balsam, Benzoin or Siam Resin). Resin is the dark, oozing secretions from a tree that differs from “balsam” mainly in terms of its form and method of preparation.

Rockrose. (Also known as Labdanum, see above.) One perfumer and research scientist described it as follows on her blog, Perfume Project NW: “Some people think it smells like goat. Others think it smells like ambergris, or leather, or pine rosin, or musk. Yet others think it smells like strange, rotten fruit. Some people think it must be the smell of heaven, and others think it’s the smell from hell. Everyone seems to have a different reaction to rock rose, otherwise known as Cistus ladaniferus (also spelled ladanifer).”

Siam Resin. Siam Resin is a type of dark, balsam-ic secretion from a particular type of tree in Thailand, and is supposed to be more smoky and dark than other types of  resins. It shares some similarities with Balsam or Peru Balsam. Both smell like sweet vanilla but Peru Balsam has a cinnamon aspect too, along with that earthy, bitter edge. In contrast, Siam Resin — which used to be burned as incense — is more smoky and woody. In short, Cinnamon Vanilla with bitter green earth -vs- Sweet Vanilla with smoky, incense and wood.

resins. It shares some similarities with Balsam or Peru Balsam. Both smell like sweet vanilla but Peru Balsam has a cinnamon aspect too, along with that earthy, bitter edge. In contrast, Siam Resin — which used to be burned as incense — is more smoky and woody. In short, Cinnamon Vanilla with bitter green earth -vs- Sweet Vanilla with smoky, incense and wood.

Sandalwood: NST describes sandalwood as: “an oil extracted from the heartwood of the Sandal tree, originally found in India. One of the oldest known perfumery ingredients, the powdered wood is also used to make incense. Indian sandalwood is now endangered, so many modern perfumes use Australian sandalwood or synthetic substitutes.” (Source: NST) The best type of sandalwood is supposed to be red Indian sandalwood, also known as Mysore sandalwood. Australian sandalwood is usually not as rich and sweet. The scent of Sandalwood can vary depending on the type used but generally, it has a sweet, slightly cedar woodsy smell with sharp, sometimes acrid vanilla undertones. It can sometimes take on a faintly medicinal note, but there is always an underlying sweetness and vanilla element lurking at its heart.

Sillage. Sillage refers to how much a scent emanates. Can you smell the perfume only if you’re very close to someone, or can you smell it from across the room? If a perfume has very little sillage, people say it’s “close to the skin.”

Soliflore. Soliflore refers to “a fragrance which focuses on a single flower, or which tries to recreate the aroma of a single flower. Soliflores may in fact have more than one floral note, however.” (Source: NST)

One type of Styrax tree which creates the resin used in Tubereuse Criminelle and in other fragrances.

Styrax. Styrax is essentially yet another type of resin. Bois de Jasmin states as follows: “It is a beautiful dry, smoky, spicy note, with a distinctive leather and incense facet. It is the least sweet and vanillic out of the balsams I have described here. A beautiful note of styrax can be noticed in the drydown of Serge Lutens Cuir Mauresque, Bois Oriental and Tubéreuse Criminelle. It is generally a supporting character, but smell Bond No.9 Broadway Nite, and the presence of leathery styrax is unmistakable right from the top note, where it is given a nice lift by the violet and aldehydes. Also, many leather accords like Chanel Cuir de Russie, Dior Fahrenheit, and Tom Ford Tuscan Leather rely on the leathery darkness of styrax.”

Tiaré. A type of gardenia.

Tolu Balsam. (See also Peru Balsam.) Tolu Balsam is another type of resin that comes from an injured tree. Bois de Jasmin states: “Tolu also has a vanilla and cinnamon fragrance, but I notice a strong smoky and sweet note. Tolu is reminiscent of almonds and leather, a seemingly darker note than benzoin. Tolu balsam is the leading player in Ormonde Jayne Tolu as well as an important supporting note in Cartier L’Heure Defendue. A smoky, warm touch of tolu balsam in Donna Karan Gold and Robert Piguet Fracas lends their florals a spicy, rich quality, which is further augmented by other sensual, oriental notes.”

Tonka Bean. According to Wikipedia, the tonka bean comes from a species of flowering tree in the pea family that is native to Central America and northern South America. Its seeds are known as tonka beans. “They are black and wrinkled and have a smooth, brown interior. Their fragrance is reminiscent of vanilla, almonds, cinnamon, and cloves.”

Tuberose. A extremely heady white flower that, like Frangipani, is a very indolic (tending to a lushly narcotic, sometimes over-ripe, full-blown smell). That potential to be indolic is why extremely creamy, ripe tuberose scents can — on some people — bring to mind feces, mothballs or a cat’s litter box. (See entry for “Indolic.”)

Vetiver. Vetiver (sometimes spelled as “vetyver”) is the essential oil from the root of a type of grass, most commonly found in India. Chandler Burr, the New York Times perfume critic, explained it for GQ as follows: “[i]n the most basic sense, it’s a grass native to India that grows in bushes up to 4’x4′. It’s also related to lemon grass, as you can tell when you smell it. The stuff—it’s the grass’s long, thin roots that they distill—is infinitely more interesting though: deep, shadowed, astringent, earthy like newly tilled soil, and balsam-woody. It can be warm like tobacco leaves, it can have a crushed-green leaves freshness, or it can be cool like lemon verbena. Haiti produces about 80% of the vetiver oil in the world, although sometimes you’ll be putting a bit of Indonesia or Brazil on your arm as well (Haiti’s is more floral, Java’s is smokier). […] Like wine, the scent of vetiver oil improves as it ages: the best of it is made with roots that have been aged somewhere between 18-24 months; the oil costs around $200/kg when it hits the market. American scent maker IFF makes it three ways: with steam (resulting in vetiver essence, which is dryer and lighter), solvent (which produces an absolute and is darker, with the scent of rich dirt), and a new technology called “Molecular Distillation” that uses carbon dioxide to yield a scent that’s extraordinary—strongly grapefruit, fresher, zestier.”

Ylang-ylang.

Ylang-ylang. Ylang-Ylang comes from a bright, banana-yellow flower and has a rich, heady, sweet, floral smell that is slightly fruity and custardy. One commentator called it “the eccentric sister to jasmine” but it’s also often compared to such flowers as tuberose, frangipani, and tiaré. Personally, I think it has a richer, fruitier and, definitely, spicier scent than any of those flowers. As a side note, the smell of ylang-ylang has long been considered to be both an aphrodisiac and soothing.

I could see Santa giving you a Rockrose for Xmas if your bad 🙂 I love this informational posting. Thanks!

Hahaha, it does look like a giant lump of… something, doesn’t it? In my case, though, I suspect Santa would punish me with Acqua di Gio — mens/womens, I’ve been known to go on a bit of a rant about it once or twice. On second thought, he might give me a Montale. *shudder*

I’m really glad you enjoyed the glossary and found it informational. 🙂 Thank you so much for letting me know. I found myself needing a refresher after the Alahine review; it’s so well-blended and used such high quality ingredients, I couldn’t always tell what was responsible for what smell!! But, in general, I sometimes find I need to remind myself how some things smells. For example, it’s not easy to remember all the differences between diff. resins or diff. indolic white flowers. Yes, the differences may be very small, but they can still count! I also find I need particular help with some of the new synthetic compounds like calone for example or Ambroxan (which was a totally new term to me, along with Opoponax). Ultimately though, I’d like to make my blog accessible to everyone, not just those who are experts or well-versed in the niche perfumes. I have a secret agenda, you see: lure them in with stuff that doesn’t seem too intimidating, and then get them to throw away their Acqua di Gio or Angel once and for all…… *grin*

Pingback: Perfume Review – Serge Lutens Serge Noire: Janus & The Cloven Beast | Kafkaesque

Abergris looks a lot less pretty than it smells, which is alarming given that it’s basically vomit! LOL. It’s funny to envision the discovery of amergris:

SCENE – A beached whale on a shore, in a pile of its own vomit (possibly due to a night of drunken escapades)

Passerby: What’s this wonderful, heavenly smell?

[Passerby promptly rolls around in said whale barf]

END SCENE

Not if the passer-by was a perfume addict. In that case, they would run in and sweep up the vomit by the bucket, sell it for gazillions and retire rich to a room filled with ALLL the hundreds of perfumes they were now able to afford! *grin*

Seriously, the real stuff…. worth its weight in gold. Quite literally, I believe.

Pingback: Perfume Review: Tom Ford Black Orchid Voile de Fleur | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Serge Lutens Tubereuse Criminelle: Genius but not Felonious. | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Les Néréides Imperial Opoponax: Evoking the Guerlain Classics | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review: Amouage Jubilation XXV: An Oud Fit For A Sultan | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Amouage Jubilation 25: Scheherazade & Seduction | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review: Tom Ford Private Blend Amber Absolute | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Chanel Les Exclusifs Cuir de Russie: The Legend & The Myth | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Robert Piguet Bandit: “Beautiful but Brutal” | Kafkaesque

kafka …. am lost dear …. i dont know what to say after reading this 😀 i loveeeeee your blog and am so addicted you know 😀 i dont know a single thing but will learn slowly

I’m so glad you like it, Rashmi. And, no worries about all of this being totally new to you. We *all* started somewhere! All of us! But learning some of the terms can really be useful to you in getting to know about perfumes because it will tell you what smells like what and why. You can find out what sorts of perfumes you may like or definitely won’t like based upon knowing what the key ingredients are. And, nowadays, few perfumes are just made with “rose, vanilla and musk” or obvious terms like that. The notes are full of foreign-sounding terms. But once you get a rough sense of what those things mean, you’re all set! I promise, it’s not as hard as it looks. 😀 xoxox

Pingback: Perfume Review – Robert Piguet Fracas: The History & The Legend | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review: Tauer Perfumes L’Air du Desert Marocain | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Tom Ford Private Blend Noir de Noir: Henry VIII’s Tudor Rose | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review- Serge Lutens Borneo 1834 | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review- Serge Lutens Chergui: The Desert Wind | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Chanel Les Exclusifs Sycomore: Mighty Vetiver | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Preliminary Review – Chanel Les Exclusifs 1932: Sparkling Jasmine | Kafkaesque

Pingback: “The People v. Amarige” – Prosecution & Defense | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Ormonde Woman by Ormonde Jayne: The Dream Landscape | Kafkaesque

Pingback: A Beginner’s Guide To Perfume: How to Train Your Nose, Learn Your Perfume Profile, & More | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Roberto Cavalli Eau de Parfum: My Guilty Pleasure | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Tom Ford Private Blend Oud Wood: An Approachable Oud | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review – Trayee by Neela Vermeire Créations: A Vibrant Kaleidoscope | Kafkaesque

Pingback: Perfume Review: Absolue Pour Le Soir by Maison Francis Kurkdjian | Kafkaesque

Love it all! Funny but the immortelle that I purchased from Eden Botanicals smelled like bacon to me (this was not a bad thing 🙂 ) but when i added a bit of bourbon vanilla to it that bacon smell dissipated and what was left was this gorgeous caramel note.

Mmmm, sounds delicious!! Caramel! How funny about immortelle smelling like bacon to so many people. LOL.

Pingback: The Doctor who married a Perfumista in Vienna | The Fragrant Man