I thought some of you might be interested in a 2004 piece I wrote on Japan’s powerful, fierce Empress, then later Dowager Empress, Nagako. It is, among other things, the tragic story of a victim turned abuser and of a woman who rose to become a real force and power behind Emperor Hirohito.

The Early Years

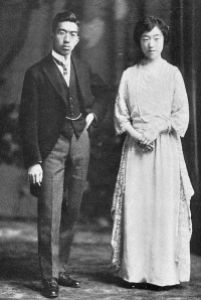

Dowager Empress Nagako was the wife of Emperor Hirohito and the mother of Japan’s current Emperor, Akihito. When she died, only four years ago at the age of 97, she was also the longest living empress consort in Japanese history. She was Crown Princess from 1924 to 1926, Empress from 1925 to 1989, and Empress Dowager from 1989 to 2000. In short, she was close to the throne for 76 years!

She was born on March 6, 1903, Tokyo, the eldest daughter of Prince Kuni who headed one of the eleven cadet branches of the Imperial Family. Her father, a descendent of a 13th century emperor, was the last of his line. And she, in turn, was the last imperial princess to marry into the Japanese Imperial Family.

Her engagement to her distant cousin, then-Crown Prince Hirohito, was unusual for several reasons. For one thing, Princess Nagako had been chosen, in 1914, when she was only eleven years old. According to historian Jeffrey W. Taliaferro, it occurred as follows:

On 14 January 1914, the Empress Sadako invited a number of aristocratic and royal girls to tea at the Concubines’ Pavilion at the Imperial Palace, while Crown Prince Hirohito cast his eye upon them, hidden behind a sliding screen. He selected the princess as his future bride. http://www.geocities.com/jtaliaferro.geo/showa.html

Age was a minor issue as compared to the Nagako’s lineage. The simple fact is that Nagako didn’t have the background of most imperial consorts. She may have had a royal father but he came from a very minor offshoot of the Imperial Family. Her mother’s background wasn’t much help either, because Lady Shimazu Chikako descended from feudal nobility, as opposed to one of the illustrious aristocratic court families. But the real issue was the Fujiwara factor: for centuries, almost all the Japanese emperors and crown princes had married women from the powerful Fujiwara clan.

Age was a minor issue as compared to the Nagako’s lineage. The simple fact is that Nagako didn’t have the background of most imperial consorts. She may have had a royal father but he came from a very minor offshoot of the Imperial Family. Her mother’s background wasn’t much help either, because Lady Shimazu Chikako descended from feudal nobility, as opposed to one of the illustrious aristocratic court families. But the real issue was the Fujiwara factor: for centuries, almost all the Japanese emperors and crown princes had married women from the powerful Fujiwara clan.

The Fujiwara dynasty was one of the most illustrious families in all Japan and, in some ways, was almost like the de facto imperial family. The reason for this is that they were always chosen to act as imperial regents or Kanpaku. Lest you think this was an occasional position due to an emergency involving the Emperor, let me assure you it wasn’t. The Fujiwara clan had acted as “regents” to Emperors who were young and old, incapable and perfectly capable. In short, they served as the real emperors and purveyors of power, behind the scenes, while the titular ruler was just a ceremonial figurehead. http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Nagako

Thus, despite Nagako’s impeccable lineage, hot debate raged over her eligibility to become the wife of a crown prince who, upon ascension to the throne, would be revered as a “living God.” Adding to the controversy was political intrigue at the highest level.

One of the most powerful men in Japan came forward to allege that the princess was colorblind, thus making her ineligible on genetic grounds to take a place in the imperial line. Field Marshal Yamagata headed a samurai clan that was a rival to Nagako’s mother’s family and he wanted the Crown Prince to choose a bride from his own clan.

Yamagata, the principal architect of the Imperial Japanese Army and arguably the most powerful man in late Meiji and Taisho Japan, vehemently opposed the engagement for seven years. In 1919, Yamagata arranged the publication of a medical journal article, which alleged a history of color-blindness in the family of the princess’s mother, the Shimazu of Satsuma. This alleged hereditary malady, he argued, would damage the flawlessness of the Imperial bloodline. Prominent newspapers printed the allegations and Yamagata demanded that the Imperial Household Ministry annul the engagement.

Prince Kuni vowed to commit suicide and kill Nagako if the Imperial Household Ministry cancelled the engagement. He allegedly enlisted the aid of nationalistic Tokyo gangsters to thwart Yamagata. The gangsters organized large rallies in Tokyo, which denounced the plots against Princess Nagako as disloyalty to the throne. Emperor Taisho intervened on Nagako’s behalf by dismissing the article on color blindness. “I hear,” the emperor told Yamagata, “that even science is fallible.” http://www.geocities.com/jtaliaferro.geo/showa.html

The engagement was finally announced on June 19, 1921 by the Imperial Household Ministry, the IHA’s predecessor. However, the couple did not get married for several more years. The Princess was still quite young but the main reason was what happened in 1923, the year the imperial wedding was supposed to take place. That year, a huge earthquake destroyed half of Tokyo, killing 10,000 people. The wedding was delayed once again.

All during this time, Nagako was being groomed for her new position. In 1914, within a month being chosen by the Empress and Crown Prince, Nagako left school. She began receiving years of private instruction to assist her in her role as the future empress. She was taught:Chinese and Japanese literature, French, calligraphy, poetry composition, needlework, flower arrangement and the intricacies of court etiquette, all under the direction of seven tutors. During that period, she and crown prince only met nine times, and never in private. Id.

The wedding finally took place on January 26, 1924. Nagako was 20, her groom, 22. Less than two years later, on December 25, 1925, Hirohito ascended the throne and she became Empress.

The New Empress

Nagako wasn’t controversial just because she broke the age-long tradition of Fujiwara family consorts and the fuss surrounding her engagement. She also caused chatter because of her difficulty in conceiving a male heir. Under Japan’s succession laws, only a male can ascend the throne, thereby continuing the family’s unbroken 1500+-year-old line.

Like Crown Princess Masako now, it wasn’t easy for Empress Nagako to have a male heir. In 1932, Hirohito and Nagako had been married for eight years but still hadn’t had a boy. Empress Nagako had borne four children, all girls, of who three had survived. She was pregnant with her fifth child and the court was in a state of unrest over the future of the succession.

Like Crown Princess Masako now, it wasn’t easy for Empress Nagako to have a male heir. In 1932, Hirohito and Nagako had been married for eight years but still hadn’t had a boy. Empress Nagako had borne four children, all girls, of who three had survived. She was pregnant with her fifth child and the court was in a state of unrest over the future of the succession.

Empress Nagako had a miscarriage in late 1932. The succession question became so serious that pressure mounted for Emperor Hirohito to take a concubine. Although the concubine system was banned by post-war measures, this was still many years before the war. However, Hirohito was deeply opposed to the concubine system, even though it was as one of the only reasons why Japan had never had problems with the succession, up to that point that is.

Under the concubine system, rotating teams of part-time mistresses, usually twelve, assigned to the Emperor by the noble families of Japan’s ancient capital, Kyoto. By custom, an emperor dropped a silk handkerchief at the door of the mistress on duty whenever the problem of his successor crossed his mind. Resulting children were brought up, not in the Imperial household, but by the families who had sent their daughters, whose sons thus founded collateral branches of the Imperial line from which new emperors could descend. At the risk of some inbreeding, concubinage ensured that a crown prince was almost always available to succeed a deceased emperor.

Murray Sayle, “Sex Saddens A Clever Princess,” (Japan Policy Research Institute Working Paper No. 66: April 2000) at http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp66.html

The concubine system may have been responsible for prior emperors, but it wasn’t for Hirohito. While his own father, Taisho, and the Meiji Emperor before him, were all sons of concubines, Hirohito was the son of Taisho’s legal empress.

Furthermore, Hirohito had abolished concubinage in 1924, the year he married Nagako. One reason was the British royal family who had greatly impressed him on a visit he made to London. After witnessing their close personal interactions, Hirohito decided he would try to emulate them and the European system. Hirohito was so impressed by the West that he also installed a nine-hole golf course on the Imperial Palace grounds, played tennis, wore Western clothes on all but the most ceremonial occasions, and ate a proper English breakfast every morning. Apparently, he developed a taste for eggs and bacon on his tour of England, when Crown Prince.

The royal court couldn’t care less about the Western system, not when the succession was at stake. After eight years without a male heir, there was widespread panic among the royal courtiers that the imperial line would be broken. The Emperor insisted on remaining monogamous but, even so, a senior royal official decided to find him a concubine. He searched high and low for a proper, and attractive, woman of high breeding:

Ten princesses were selected of whom three made the final cut, and one (allegedly the prettiest) was rumoured to have visited the palace and played cards with Hirohito (in the presence of Nagako). The monogamous Hirohito supposedly took no further notice of her. In early 1933 Nagako became pregnant again and on December 3, 1933, she gave birth to Prince Akihito. The personal crisis was over.

Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the making of modern Japan (Harper Collins 2000), at 271.

The Emperor and Empress eventually had two more children, for a total of five daughters and two sons. Only two of these children maintained their imperial status, Crown Prince Akihito and his younger brother Prince Hitachi. The reason can be traced to post-war changes to the law which sought to decrease the size of the Imperial Family. Under the 1947 changes, the princesses automatically lost their imperial status when they married commoners.

The Emperor and Empress eventually had two more children, for a total of five daughters and two sons. Only two of these children maintained their imperial status, Crown Prince Akihito and his younger brother Prince Hitachi. The reason can be traced to post-war changes to the law which sought to decrease the size of the Imperial Family. Under the 1947 changes, the princesses automatically lost their imperial status when they married commoners.

As parents, the Imperial couple generally abided by tradition, albeit with a few big changes triggered by the war. In time-honored imperial fashion, Prince Akihito, the future emperor, was separated from his parents at about the age of three and raised by nurses, tutors and chamberlains. Yet in a departure from custom, at six Akihito was sent to school with commoners in order to broaden him.

The Post-War Years

During the war, the Emperor and Empress remained at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. When the Americans began bombing Tokyo, the couple sent their children away to the countryside for safety.

After the war, the Emperor insisted on a Christian tutor for his heir, Akihito, who was being hailed as the “future hope of Japan” amidst speculation that the Emperor would abdicate. Always aware of appearances and PR, Hirohito approved the appointment of an American Quaker, Mrs. Elizabeth Gray Vining, as his son’s tutor. He was well aware of Quaker pacifism and what the symbolic ramifications would be given the war and his own reputation. As numerous historians have made clear, Hirohito was the master of manipulating his image for public consumption, especially after the war when he reinvented himself completely. See e.g., Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (Harper Collins 2000). Id.

Still, in all fairness to Emperor Hirohito, he seemed truly concerned about his son’s education. It’s been said that the only potential candidates whom he ruled out for the position of chief tutor “were bible-thumping proselytizers of some other Christian sects that were then active in Japan.” Murray Sayle, “Sex Saddens A Clever Princess,” supra. According to one commentator, the Emperor “paid Mrs. Vining US$2,000 a year from his own pocket, at a time when his personal assets were estimated at $70,000 (the Japanese royal family is far from wealthy, by international standards, even to this day).” Id.

I’m not sure Mr. Sayle is completely correct in his interpretation of the Emperor’s financial status. The question of Hirohito’s assets is a complicated one and there are numerous sources which question the Emperor’s carefully cultivated image of being impoverished. By many accounts, he was quite wealthy at the time of his death, even though it wasn’t a millionth of his prior (multi-billion dollar) net worth before the war. Furthermore, he left a multi-million dollar estate upon his death. Still, the main point is that the Emperor seemed concerned about his son’s development and took a personal role in directing his future.

Empress Nagako went along with it, just as she did with everything her husband said. She was a firm believer in protocol and in a woman’s submission to the more important man in the relationship. Especially if he was the Emperor. Nagako was always “keenly attuned to court customs, and always showed a subject’s deference to the emperor, maintaining a modest presence.” “Japan’s Dowager Empress Dies,” BBC, (June 16, 2000) at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/793352.stm.In fact, it been said that the Empress’ hide-bound observation of protocol and gender roles was one of the things which made her resent and dislike her daughter-in-law, Michiko, whom she felt took too many liberties and shone beyond the Crown Prince. But we will get to that later….

Empress Nagako went along with it, just as she did with everything her husband said. She was a firm believer in protocol and in a woman’s submission to the more important man in the relationship. Especially if he was the Emperor. Nagako was always “keenly attuned to court customs, and always showed a subject’s deference to the emperor, maintaining a modest presence.” “Japan’s Dowager Empress Dies,” BBC, (June 16, 2000) at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/793352.stm.In fact, it been said that the Empress’ hide-bound observation of protocol and gender roles was one of the things which made her resent and dislike her daughter-in-law, Michiko, whom she felt took too many liberties and shone beyond the Crown Prince. But we will get to that later….

After the war, the occupying powers and the postwar Japanese government sought to demystify the monarchy. It was all part of the plan to reduce the divine aura of the monarchy, something that had helped contribute to WWII. In accordance with the two government’s wishes, the Empress adopted a more public, approachable role. During the American occupation, she visited orphans, bereaved families and war veterans. She also became the honorary president of the Japanese Red Cross from 1947 to 1989.

The American occupational forces and the post-war Japanese government may have intended to strip the Japanese Imperial Family of their traditions, divine legacy and power, but Empress Nagako was made of sterner stuff. The day after the American occupation ended, the Empress voiced her intention to revert back to wearing kimonos in public. She was firmly of the old school and clung to the old ways.

Despite the Empress’ focus on upholding ancient traditions and manners, she was nonetheless a trailblazer in smaller, more innocuous ways. For example, she was the first Japanese imperial consort to travel abroad. She accompanied Emperor Hirohito on his European tour in 1971 and later on his state visit to the United States in 1975. On those trips, she became known for her classical elegance and her “empress smile.” http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/793352.stm

In her private life, the Empress was an accomplished painter, calligrapher and poet. Under the pseudonym To-en, or “Peach Garden,” she created a number of traditional Japanese-style paintings, specializing in still life and landscapes. She presented a painting of grapes to Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II when the imperial couple visited that country in 1971. See, “Imperial family loses witness to century’s turbulent events,” (hereinafter referred to as “Imperial Family loses”) http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0XPQ/is_2000_June_19/ai_62835986

But there was a dark side to the Empress. Her image as a devoted wife, talented artist and poet, and the warm-hearted granny of her later years stands in sharp contrast to the frequent rumours regarding her harsh treatment of her daughter-in-law, Michiko, the current Empress. Michiko was the first commoner ever to marry an Emperor, in a marriage that was a huge break from tradition.

But there was a dark side to the Empress. Her image as a devoted wife, talented artist and poet, and the warm-hearted granny of her later years stands in sharp contrast to the frequent rumours regarding her harsh treatment of her daughter-in-law, Michiko, the current Empress. Michiko was the first commoner ever to marry an Emperor, in a marriage that was a huge break from tradition.

The Empress, who was often described as “ferocious,” probably did not let Michiko forget her common background. The simple fact of the matter is that Nagako — and the IHA (Imperial Household Agency) — were horrified by Akihito’s choice. A royal aide to the Emperor described the Empress’ reaction in his diary entry for Oct. 11, 1958, shortly before Michiko was officially picked as the bride. According to the royal aide, the Empress talked to Princesses Chichibu and Takamatsu, her sisters-in-law, about the situation and cried out “something to the effect that it is outrageous” to choose a commoner. See, “Imperial family loses,” supra.

It’s been widely rumoured that the Empress tried to stop the engagement with all her might, but she didn’t succeed in changing her son’s mind. The Japanese people, however, rejoiced over the marriage and saw it as a welcome move that brought the Imperial Family closer to the people.

The couple set up house in the Togu Gosho, the Crown Prince’s unpretentious residence half a mile from the Imperial Palace. But reports continued to seep out that Empress Nagako resented the intrusion of a commoner into the family. See, Michael Walsh, “Akihito: The son also rises,” Time Magazine (January 16, 1989)(archived text not available online).

The situation was exacerbated when, in another break with tradition, Akihito and Michiko chose to raise their three children at home. Empress Nagako could barely manage the fact that the new royal was a commoner; the second break from centuries of tradition was the last straw.

The Empress’ disapproval and dislike of the new Crown Princess did not soften over time. In the early 1960s, the nation watched as then-Crown Princess Michiko, previously described as “effervescent” and the epitome of womanly charm, grew gaunt and somber. She even lost her voice for 7 months. It’s unclear if she couldn’t speak or if she simply didn’t want to but, either way, one thing was certain: she was no longer the woman she had been before her marriage. Rumours swirled that she had had a complete nervous breakdown.

All fingers pointed back to Empress Nagako, although it must be said that she had help from the ever-wonderful IHA. It was only upon Nagako’s death in 2000 that the cause of Michiko’s deterioration was publicly identified: the Reuters news agency bluntly stated that the Dowager Empress had reportedly bullied her daughter-in-law into submission and a breakdown. See, http://www.mmjp.or.jp/amlang.atc/worldnow/00/june/17.htm. See, also, http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Michiko.

Nagako was truly Japan’s version of China’s “The Dragon Lady,” or Empress Tzu Hsi. She was imperious, extremely strong-willed, tough as nails, controlling (behind the scenes), arrogant, unable to relate to the masses, coldly haughty, and royal beyond royal. She was supremely aware of her imperial lineage in an ever changing world that became more and more modern, that had less and less regard for the old ways. She had no tolerance for modern or relaxed standards, even in her own son, let alone his poor, commoner wife. She might have been born in the early years of the 20th century, but Nagako was a thoroughly 19th century woman, especially once the royal tutors finished with her.

The Empress often had a wonderful smile for the general public but, privately, she was haughtily aware of her background and disdainfully contemptuous of even the smallest restriction on imperial rights. Especially after the war. She took the Emperor’s forced renunciation of divinity very badly, as shown by letters to her son at the time.

For all her traditional ways, Nagako essentially played the gender game and gave lip service to the socially superior male in Japan’s male-dominated society. She acted in a passive and submissive manner towards her imperial consort, but, at the back of her mind, she always remembered and heeded her father’s pre-marital advice that Hirohito was a weak vessel whom she was duty bound to prop up. And so she did. While Hirohito was often indecisive, she forced him onto to action, at least in the private sphere. Nagako was too much of a product of 19thcentury thinking to even try to influence the Emperor in national or political matters. In all else, however, she held sway.

An intimidating, multi-talented, highly trained and educated Empress, she was a powerful presence at the Japanese court for decades. And she certainly seems to have frightened her daughter-in-law into a collapse. Given the grief she herself was given over her own engagement to Hirohito, the irony is huge….

Nagako’s marriage to Emperor Hirohito lasted 65 years, longer than any other imperial couple in Japan’s history. When Hirohito died in 1989, she assumed the title of Empress Dowager. At that time, she was in failing health herself. Her last public appearance was in 1988. During her remaining years, she lived a reclusive life at the couple’s residence, the Fukiage Palace, looked after by a full, almost medieval imperial court of some 40 court ladies and medical experts.See, “Imperial family loses,” supra.

In 1995, Nagako became Japan’s longest-living empress dowager when she turned 92, surpassing Empress Kanshi, who died in 1127. At the time of her death at the age of 97 in 2000 she had been an empress for 75 years. Akihito granted his mother the posthumous title of Empress Kojun. The Emperor chose the name due to its meaning which is as follows: “The character for ‘Ko,’ which symbolizes fragrance or beauty, is a reference to the late Empress’s artistic name (Toen or ‘Peace Orchard’). The character for ‘Jun’ refers to the Empress’s kind-hearted personality.” Taliaferro, supra, http://www.geocities.com/jtaliaferro.geo/showa.html

“Kind-hearted” — not quite the phrase I would use to describe the Empress. On a good day, I would opt for The London Times’ description of her as “ferocious;” on a bad day, well…. I’ll let you fill in the blanks.

One thing, however, is undisputed: she was an intimate insider to some of the most important events of the 20th century. But the Empress was more than just a passive observer. The Empress might have been a 19th century woman in terms of upbringing, but she helped to shape the post-war monarchy and she definitely impacted the current Imperial Family. The Empress didn’t always adapt well to the changes – and she definitely was a martinet – but she was also one of the best examples of the multi-layered, dichotomous undercurrents running through the Imperial Family, their situation, the conflict with the past, and their uneasy adjustment to their modern, post-war life.

[ED. NOTE: If you’re interested in the Japanese Imperial Family, its history, the Imperial Household Agency, and the ultra-nationalist politics at play, I have written a four-part analysis on the issue. Part I of the Chrysanthemum Throne series covers more historical background, while Parts III and IV covers the post-war era and the current imperial family, along with the plight of the current Crown Princess, the tragic Masako.]

A refreshing change of pace and a very fascinating read – thank you for sharing this. 🙂

I’m so hugely pleased that you enjoyed it. It means a lot to me, especially as I know people don’t come to this blog for my

obsession.. er… interest in history. LOL. Thank you so much for stopping by, Haefennasiel. 🙂Unfortunately I can’t bear history, no matter how well written ( and this looks interesting, actually). It’s just that my eyes and brain always shut down after one paragraph of history. This is one of my more detestable lacks.

Funny Neil…as soon as I saw Japanese empress I thought of you and how much you might enjoy reading this!

Interesting read on a “ferocious” woman…wonder what perfume she wore :D!

I know, in theory it does interest me, especially for the Japanese element, and especially if she is ferocious (go on then, I’ll give it another go….) but I have GREAT difficulty concentrating on history. At university (Cambridge, so I’m hopefully not TOTALLY dumb, I tried to do an Italian history course and after one ‘essay’, the professor laughed me out of the room. When it came to literature however I was like a duck in water. I just can’t bear the ‘factual’ nature of it all. I know a historian will argue the case for her subject passionately and I do believe that history is important (I tell my students that), but, you know, I just HATE IT!

Neil (may I call you Neil or Ginza?), please don’t force yourself. Truly, don’t. My feelings won’t be hurt in the slightest. As I explained in another reply just now, I have to get these things up on the blog but I certainly don’t expect anyone to read them. In fact, I would highly recommend that the perfume people do not. They are far too academic and long (though this Nagako one is perhaps the shortest and most casually written). And I can sympathize with your mental block; I get the same thing when numbers (or science/math) are involved. 🙂

GinzaInTheRain, believe me, I didn’t expect ANYONE to read ANY of these. LOL! If I could have just posted them, and shoved them to the back or archives, without taking up space or people even realising, I would have done so. I wanted everything in one place, so I have to post these historical pieces from time to time, but I know it’s a little “WTF” for a blog devoted primarily to perfume. Still, I’m constantly surprised how many hits I get for the historical stuff, especially the ones on gastronomy, famous chefs, and royal food recipes. But believe me, I certainly don’t expect any of the perfumistas to read ANY of these articles! xoxox

Why not? they are actually interesting to read :D!!

I think they should; keeping it eclectic is great I think..

Another interesting read. I have never had any interest in the Japanese Imperial family but this was pretty fascinating.

I’m so glad you enjoyed it. 🙂 The reason why the Japanese Imperial Family so fascinated me is because the IHA is truly the last vestige of the sort of Machavellian, secret, black organisation like that which wrought so much damage during the time of the Inquisition or the Borgias. It’s almost hard to wrap one’s mind around their power and their nefariousness (imo). Combined with the political intrigues, the God issue, and the ultra-nationalistic underpinnings to everything the Japanese Imperial family once did, the result is something wholly medieval in a modern world. Even if you take away the other power players, the intrigues swirling around people like Empress Nagako is pretty dark. And, in the case of Empress Nagako, the irony of what she endured, then passed down to Empress Michiko, and now, the 3rd generation with the misery of poor, bullied, tormented Crown Princess Masako — well, it’s truly a soap opera with some rather tragic outcomes.

I’m going to work my way through your history posts. This woman was amazing. And you did well conveying how amazing in a rather brief space. I love contradictions in a person – the gentle grandmother vs the cruel mother in law and oh the irony, yes, the irony of her wedding once under attack and her going on to attack her son and daughter-in-law’s wedding.

So nice to see you again, Mridula! And how lovely of you to read my old historical stuff. (Frankly, it’s a lovely shock and surprise. LOL.) Yes, the story of Nagano and her daughter-in-law (not to mention the 3rd in the generational cycle) is one full of terrible irony. In Masako’s case, it verges on tragedy, in my opinion. Very depressing, all around. 🙁

This was interesting to read, even though I don´t know all that much about Japanese history and what I do know goes farther back in history during the feudal era. I have mostly concentrated on the folklore and Japanese mythology personally, and prefer time periods that are a little (or a lot) farther behind in history, but I truly didn´t knew about the present Royal family. This was very informative but that Nagako woman sounds as unlikable as ever, worth of being loathed. On the other hand I find interesting how the queen makes life miserable for the new princess, is that jealousy towards the younger woman? Or a pathetic type of revenge, inflicting the same thing they endured when they were younger? Either way I find that kind of attitude quite pathetic and immature…

Nagako was a royal through and through and some tongues said she was the real emperor as well.

Pingback: On 6 March in Asian history | The New ASIA OBSERVER

By far the most complete analysis that I have read of Nagako Empress Kojun.. Thank you for writing and publishing it.

You’re very welcome. Thank you for stopping by and letting me know. I appreciate it, since my history pieces were from long, long ago and the focus of my writing has changed to other areas. It’s nice to know the old Japan articles are still of interest to some. 🙂

Nicely written. You made the dry stories more personal and relatable.